Constructing a Fraud

For years, a contractor has been scheming homeowners, businesses and racetracks out of millions of dollars, depleting life savings and inflicting severe emotional distress. His victims wonder where they’ll get justice.

By Myers Reece

A contractor convicted of felonies over a decade ago in Wyoming for defrauding customers has revived his operations and moved across state lines, leaving behind more than 150 known victims across multiple states, with most in the greater Flathead Valley, although the number could be much higher, according to numerous interviews with victims and other detailed evidence examined by the Beacon.

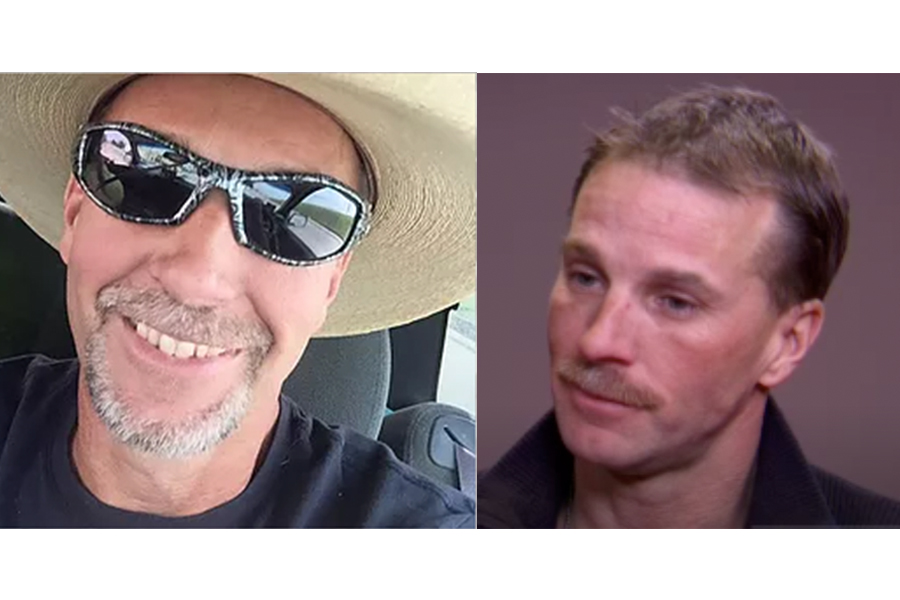

A conservative calculation is that the contractor, Craig Draper, has taken over $2 million from the known victims, although that doesn’t account for the many additional hundreds of thousands of dollars spent on undoing and redoing Draper’s shoddy work and damage, refinancing loans, impact on credit and other expenses, along with emotional distress, which victims say has been the biggest price they’ve paid.

Draper was charged with four felonies for contractor-related crimes in 2005 and 2006 in Sweetwater County, Wyoming and convicted of conspiracy and obtaining property by false pretenses, according to court records. The illegal activity outlined in charging documents is identical to the descriptions of his clients’ experiences in Montana from 2016 to late 2018. Victims have also come forward in Wyoming, Washington and Idaho over the same time period. His business has been operating as Architectural Design and Innovations, referred to as ADI Builders.

While Draper has worked from the Bitterroot Valley to Helena to Billings, the center of his Montana activity has been the state’s northwest corner.

Members of the car-racing community also say Draper was simultaneously perpetuating another multi-faceted fraud as operator of the now-named Mission Valley Super Oval, bilking untold thousands of dollars from sponsors, suppliers, vendors and racers before disappearing late last fall, which is when his construction victims say he fell off the map.

Victims across the Flathead Valley and beyond have contacted attorneys, law enforcement, legislators, the state Department of Justice, the state Department of Labor and Industry, and the FBI, which has been investigating the case, according to people who have been in contact with FBI agents. The FBI would neither confirm nor deny an investigation, citing policy.

The Flathead County Attorney’s Office has two reports on file from December 2018 stating that the U.S. Attorney was filing charges against Draper, although a spokeswoman for the U.S. Attorney’s office said Department of Justice policy is to neither confirm nor deny whether there’s an investigation.

Frustrated with no arrest, charges or adequate answers nearly a year after first bringing their claims to authorities, and worried that Draper will continue taking advantage of other people, victims have decided to take their story public. In addition to seeking a semblance of justice, part of their goal is to start a public discussion over what they see as a framework of laws that allows dishonest contractors to operate freely in Montana.

“Where are our rights? Where are the laws protecting us?” Theressa Crosby said from the kitchen of her Kalispell home recently, surrounded by other people who say they were defrauded by Draper, as well as a former employee and a contractor hired by some victims to repair Draper’s damage at their properties.

“Why are people like him — and there are others like him — allowed to do this and run free? We don’t know where to turn to.”

Construction

Crosby and her husband have lost roughly $150,000 to Draper, between checks written directly to him early on and the costs of redoing his poor work. The project remains incomplete, and the Crosbys, sapped of funds, chip away on their own time. Like others, they also had to remove a pre-lien that Draper placed on their property.

But it wasn’t until Crosby, realizing she’d been scammed last spring, started posting warnings on social media to avoid Draper and received responses from other victims that she began growing into the unexpected role of victim’s advocate.

“My husband and I said, ‘Oh my gosh, this guy’s a professional,’” she said.

“We were able to get out of it — we’ve lost a lot, but we got out of it,” she added. “But what about all the others who can’t?”

Crosby has compiled a binder with over 850 pages of evidence building a case of Draper’s alleged widespread fraudulent activity. She is both strong-willed and relentless, approaching the task with the meticulous fastidiousness of a good detective. Her binder includes bid proposals, invoices, falsified licensing and insurance documents, bankruptcy letters, bank statements, background checks, text message exchanges, social media posts, letters, photos and more. She has provided copies of the binder’s content to FBI agents.

Crosby also administers a private Facebook page that serves as a forum for Draper’s victims, of which there are 124 and counting. She has also been in contact with 38 additional victims, who are methodically compiled in her binder, and believes “there are many more.” The list does not include building material suppliers and other vendors, utility companies, subcontractors, landlords and others who have been impacted.

The victims’ $2.1 million in out-of-pocket losses directly to Draper calculated through Crosby’s research, not counting the multitude of other expenses and losses, range from a few grand per household or business to the hundreds of thousands. People have depleted life savings and 401K accounts. Some have been forced to move.

One lawsuit filed in Flathead County District Court sought a jury trial and requested compensation. Draper was served with the suit, but because he never responded, the court issued a default judgment awarding the plaintiff $442,869.

The lawsuit was one of eight civil actions filed in Flathead’s district court as of last week, including five complaints filed by the Department of Labor and Industry (DLI) for lost wages on behalf of former employees. In each DLI complaint, a compliance officer and the court ruled that Draper owed restitution. There is also a civil case against Draper in Lewis and Clark County.

Cody Allegro, a former employee, said he was kept in the dark about Draper’s activities and use of clients’ funds, but over time red flags began emerging. Once the full picture crystallized, he said he stayed on to try to right ADI Builders’ wrongs, and after quitting he continued helping clients. He said he’s spent so much time at Crosby’s house, “I think of her as family.”

Allegro said Draper withheld employees’ income for taxes and child support, as required by law, but either never paid any of it or only some of it, leaving employees in trouble with the IRS and courts.

“I told the FBI, ‘Look through my phone. You can see everything,’” he said.

The situation resembles a case featured in a 2010 and 2011 Beacon series about a contractor named John Mulinski, who bilked numerous homeowners and subcontractors throughout the Flathead and beyond. Mulinski was found guilty in U.S. District Court in Missoula of three felonies for wire fraud and sentenced to 57 months in prison and $138,000 in restitution for wire fraud, on top of charges in other states.

A state investigator at the time called the Mulinski case “the biggest case I’ve run across in Montana,” and the Draper case appears to rival if not surpass that one in scope, at least regarding his Montana activities.

The Beacon tried to reach Draper on three phone numbers that he had used while interacting with victims, but they were alternately disconnected, no longer in his name or located at a residence he no longer inhabits. A message left on his wife’s cell phone was not returned. Attempts to reach him through four email addresses were similarly unsuccessful, receiving no reply from three addresses while one was no longer active.

One of Draper’s Facebook pages has been removed, while on another the most recent post is from Feb. 7, 2016. That Facebook page lists him as “owner at A.D.I.,” says he studied computer science at “M.S.U.” and states that he’s from American Fork, Utah. Multiple people have said he uses other Facebook accounts under aliases to keep a watch on his past clients and acquaintances.

The website for ADI Builders was recently taken down, but in a screenshot taken by the Beacon in October, Draper describes himself as a family man with a “vast amount of experience” in construction who understands “the difference between a quality job and one that just looks good but doesn’t last.” Former employees and victims say they aren’t aware of any jobs of any size that Draper completed in Montana.

“Craig knows the industry and over the years has established a wealth of resources to handle any job at any time,” Draper’s bio stated.

Victims describe Draper as a smooth talker who always had an answer for any question and projected an air of expertise in construction. Interview after interview described Draper asking for a down payment up front for materials and then arriving to pick up the check before disappearing or, more often, performing enough work, or acting as if he was performing enough work, to give the impression he was following through, hoping to collect another check based on a manufactured reason. He spent his days crisscrossing the valley, state and beyond collecting checks and speaking with customers, maybe working for a while or dropping off crewmembers, only to hit the road again.

Upon request, Draper would provide documentation showing he was licensed, insured and bonded, but victims later found out the paperwork was falsified. Victims also say he would provide references that turned out to be family members or accomplices, and he would show homes as examples of his work that later turned out to be built by somebody else. Everybody interviewed said Draper worked hand in hand with his wife, Stephenie. Other family members were also involved in various ways, they said.

When progress on projects stalled or never moved forward, Draper reached into an arsenal of excuses and rationalizations, typically culminating in the assertion that he needed more money to buy more materials and advance the project. Even as red flags emerged, victims say he had a way of explaining everything, and by that point they were indebted to him through payments and perhaps work already started. Later, when victims would contact building suppliers, they found out Draper never purchased any materials or used their money on other accounts.

“I’m astounded by the number of ways he had to take your money,” said Deb Sullivan of Lakeside.

Sometimes Draper would get fired; other times he would simply disappear. If he was fired, victims say he often retaliated with threats, as documented in detail by text exchanges and other correspondences collected in Crosby’s binder, leading some to install home-security systems. The work he did perform was typically shoddy, worse than if nothing had occurred, and would require more thousands of dollars, perhaps tens or hundreds of thousands depending on the project, to undo and repair. It appears he had no deep knowledge of construction.

“I’ve been doing this since 1980, and I’ve never witnessed anyone who was so inept,” said Larry Keller, a contractor hired by Crosby and others to repair Draper’s damage. “It’s like he didn’t even try to do it.”

Or, as Crosby puts it: “It’s more than a bad job. It’s destruction.”

One Kalispell victim, Marsha Shepard, says she lost the bulk of her life savings to Draper, and has been living in a home with severe water damage and mold for two years since firing Draper. His firing came on the heels of a prolonged headache that grew into a nightmare. He had agreed to build an addition onto her garage and enclose a patio area to be used as a dining room, part of Shepard’s retirement dreams.

Instead, Draper tore up asphalt in the driveway, erected the bones of walls with non-weight-bearing beams, started a faulty roof and punched a multitude of pathways for outside water to leak into her home. She lived for a year with fans and air purifiers on full blast in the basement, yet the mold grew. Her son and his girlfriend help her attempt to make piecemeal repairs when possible, but her funds are essentially gone.

“All those dreams are out the window,” Shepard said from her Kalispell home recently.

A 75-year-old retiree in Helena, who preferred not to be named out of fear of retaliation, said she and her ailing husband hired Draper last summer to build an addition to their home and a shop on their newly purchased property. They had moved to Montana from Oregon so her husband, a veteran, could be near Fort Harrison and closer to their kids in his final days.

As with other clients, she said progress was barely perceptible, and the work Draper did complete was full of errors.

“He wasn’t here two full days the entire time,” she said. “He’d stop by for an hour or two, bring crewmembers once in a while, maybe one guy, just enough to show up and find a reason to collect more funds.”

Draper received two installments of $20,000 from the couple.

“We came to find out he never ordered anything and paid other people’s bills with our money,” she said. “Then he just disappeared and never came back.”

Her husband, livid and heartbroken by the prospects of leaving his wife behind with an albatross of a project, traveled to Lakeside, where Draper had been living, with intentions to settle matters on his own. When he arrived, he found an angry landlord, who said Draper had ditched out without paying several months’ rent.

On Feb. 5, the day her husband died and with the temperature 27 degrees below zero, her heat cut out due to mistakes Draper had made, unbeknownst to the homeowners, when he rerouted the HVAC system. For three days, she sat on a lounge chair in her living room with blankets covering the windows and doors to retain what little heat remained, and space heaters directed on her body, while a new HVAC company fixed the system.

“When I retired, the savings we had is what we had to work with,” she said. “After (Draper) took most of it, it’s been very difficult, especially now that I’m alone, to try to make ends meet to have the funds to be able to pay the contractor to finish the project. But that’s what all his victims go through. Mine is not a unique situation. I’m just sad because my husband passed away without seeing this resolved.”

Centsible Auto Sales in Evergreen was among a number of local businesses that Draper targeted. Blake Thornton, Centsible’s business manager, preferred not to disclose the amount Draper swindled them for, but it was a significant sum. Furthermore, Draper filed a lien on the property after he was fired, forcing the auto business to enter a tedious legal process to get the lien removed.

Thornton said building material suppliers throughout the area have their own horror stories. Like other victims, he said Draper left town after word spread.

“He pretty much ran out of people to hose in the valley,” Thornton said. “He had so many irons in the fire and was working so many people over, we all started getting wise to him. The scale at which he did this was unreal.”

The interviews echo the affidavit for a 2006 felony conspiracy charge filed by prosecutors in Sweetwater County, Wyoming, which states that an investigation by law enforcement “revealed a pattern of activity by Craig Draper and (former wife) Melody Draper which tends to indicate an intent to defraud their customers.”

The affidavit says the Drapers’ fraudulent activities included “the billing and collection of money for work which is never completed and for materials which are alleged by Craig and Melody Draper to have been ordered and/or purchased for customer’s projects but which, in fact, have either never been ordered or are never provided to the customer as well as false statements made to customers by Craig and Melody to facilitate such actions.”

Draper was found guilty that year and sentenced to a minimum of four years and maximum of 10 years in the Wyoming State Penitentiary. That conviction came on the heels of a 2005 conviction in Sweetwater County for obtaining property on false pretenses, a felony, also related to his construction activities. That charge was initially one of three felonies, including two counts of fraudulently obtaining money by a contractor, but the other two charges were dropped.

Draper still owes $157,210 of his court-ordered $172,991 in restitution to victims for his Wyoming crimes. He was also named in multiple civil lawsuits.

In 2010, Draper appeared on a Wyoming PBS episode about the Casper Reentry Center entitled “Criminal Rehab” to describe how the center’s therapeutic community, as an alternative to prison, helped him become a changed man. In the interview, Draper gave a tearful account of reckoning with his past, finding God and undergoing a personal transformation. He spoke of a life of addiction, alcoholism and crime leading up to his imprisonment, beginning at age 9.

Draper said he had paid his debts to society and was making good on his restitution obligations. He never mentioned construction or the nature of his crimes.

“It sounds too good to be true,” the interviewer said.

“Well, it takes a lot of work … but inside everybody is the willpower,” Draper said, later adding: “I used every tool they gave me and put it in place in every part of my life, and was bound and determined never to go back.”

“There’s a new life out there for everyone,” he concluded, “but you’ve got to want it.”

Racetracks

The bio on ADI Builders’ now-removed business website also described Draper as a “die hard dirt track racer and owner of Cloud Peak Raceway.” His Facebook page that remained live as of April 17, though not posted on for three years, is mostly dedicated to car racing-related posts, including a few announcing progress in remodeling and cleaning up a speedway in Sheridan, Wyoming. It also has inspirational quotes such as: “No matter how educated, talented, rich or cool you believe you are, how you treat people ultimately tells all. Integrity is everything.”

According to news reports in The Sheridan Press, Draper entered into a lease-to-purchase agreement with the owners of the town’s racetrack in February 2015. The newspaper reported the track hadn’t “seen a race car in nearly five years,” and in the spring of that year, “the Sheridan community rallied together to reintroduce dirt track racing to Sheridan,” an exciting time for the community.

But a little over a year later, Draper announced on Facebook on June 3, 2016 that he had closed the track, citing “ongoing misrepresentation and theft,” as well as “conflicts with a few individuals who were involved with the track before.” But the story went on to detail a number of lawsuits and legal proceedings against Draper, as well as Draper’s eviction and termination of lease due to lacking an insurance policy.

The legal claims against Draper for his tenure at Cloud Peak Raceway, according to The Sheridan Press, included multiple failures to pay for advertising, insurance premiums and other expenses.

Draper left Sheridan and quickly found a nearly identical situation: a small community hoping to revive its dormant speedway, this time in Polson at the Mission Valley Speedway. Draper secured a lease with the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes to run the track.

According to interviews, Draper advertised himself as a highly knowledgeable operator and specialist in resuscitating tracks. As in Sheridan, it was an exuberant time in the community, and Draper presented himself as the man to turn that enthusiasm into reality. And in some ways, he did just that, said Bobby Stinson, the pit boss during Draper’s time at the track.

“He was a really good promoter,” Stinson said. “The only positive thing he did was bring us (in the racing community) all back together. You could say Craig did bring racing back, just in the wrong way.”

The first year went relatively smoothly, with racers willing to overlook reports of Draper’s misdeeds coming out of Sheridan: “We were so excited we didn’t give a crap,” Stinson said. But weak spots in the house of cards began emerging the second year, and by the third year the jig was up. Racers, sponsors and vendors were dropping out en masse, having not been paid and realizing they were being duped. Track improvements went unpaid as well.

“He kept promising and promising,” Stinson said. “He had everybody excited. He had us believing the track was going to be the next big thing.”

“You give a person a shot and they keep burning you,” he added. “You finally say, ‘I can’t keep shooting myself in the foot.’”

Stinson said “you can go from Kalispell to Spokane and find vendors he has screwed over.” The list includes beer and food distributors, as well as vendors that dealt in apparel, stickers and trophies: “anything that had to do with advertising.”

“He didn’t pay them at all,” said Stinson, who sits on the raceway’s board of directors. “We didn’t know how bad it was. The board finally sat down and looked at everything and said, ‘Holy crap.’ We had to change the name of the track because so much damage was done.”

But a name change couldn’t undo all the damage, and the current board and management struggle to attract racers, sponsors and vendors because trust was so severed under Draper’s watch. People with knowledge of the particulars say Draper bilked at least $15,000 from Coca-Cola, and that only came after Pepsi had suddenly dropped out as a sponsor.

It was also revealed that Draper didn’t have insurance but had presented falsified insurance paperwork, which is illegal.

“I don’t know how he’s not in jail already,” Stinson said. “Where I’m from in North Dakota, he’d be in jail.”

“The paper trails are gone,” Stinson added. “He was smart, I’ll give him that. He knew what he was doing. He was smart, just in the wrong way.”

Malcolm Kruse, a longtime racecar driver and mechanic, was introduced to Draper, his wife and his two grown kids, and ended up taking them into his house for a while as they got settled into the valley.

“They come across as being decent, fair and caring like most people are,” Kruse said.

Like Stinson and others, Kruse said Draper took advantage of the community’s enthusiasm and trusting nature. It took a long time to begin grasping the extent of Draper’s burned bridges and fraud, and that discovery process is still ongoing.

“People don’t always go around talking about each other’s business,” Kruse said. “He skipped town, and then more and more started coming out.”

Stinson said people involved with the track weren’t even aware that Draper ran a construction business until the second year when “all of a sudden all these things started flooding our Facebook page.” Stinson and Kruse described the racing community as a big family, and the trust violations by somebody they thought was one of their own have caused intensely hard feelings. And like the construction victims, they’re unsure of the best recourse.

“If he was going to come back here, I know a couple people who don’t care if they hit him and go to jail,” Stinson said. “I don’t think he’ll show his face around here any more.”

“He hammered this racing community and almost killed it,” he added. “He messed up some lives, man.”

Seeking Justice

Crosby and other victims have held onto hope that the FBI investigation will land Draper behind bars, but they’ve grown impatient and uncertain that it will ultimately happen. A number of people took their complaints to local law enforcement, but no charges were filed. Flathead County Sheriff Brian Heino said his department looked into the complaints at the time, wrote reports and delivered them to the Flathead County Attorney’s Office, which later filed reports stating that federal charges were forthcoming.

Victims point to Draper’s arrest in Wyoming and similar cases in other states as evidence that Montana’s laws are lacking. And even in the case of Mulinski, it came down to federal investigators getting him for wire fraud, rather than Montana authorities arresting him for violating state criminal statutes. Once again, it appears that if any charges are filed in Draper’s case, they will be handed down by federal investigators.

That leaves the civil courts, which don’t appeal to many people because of the upfront costs and lack of possibility that they’ll ever collect compensation. Not to mention, it doesn’t put the perpetrator behind bars to prevent the crimes from continuing.

Randall Ogle is a Kalispell attorney representing Alan Ludwig, who was awarded $442,869 by Flathead County District Court. Ogle concedes that an asset check revealed almost nothing in Draper’s name, meaning that the chances of collecting funds are slim. He understands the reluctance to pursue justice through civil suits.

“They probably think it’s not worth the money, which is a good judgment call to make if you don’t think you’ll be able to collect,” Ogle said.

“It seems to me,” he added, “that criminal charges ought to be brought, through the federal level or state with the county attorney’s office.”

Crosby and her husband reached out to the state Department of Justice Office of Consumer Protection, only to receive a letter stating that it had been “unsuccessful in locating this company” after trying to reach Draper at addresses and numbers associated with him.

“Since we have no viable information to proceed with the investigation, we are closing our file,” the letter stated.

Crosby says she understands the need to have laws in place protecting contractors, but she thinks there can be a balance in the statutes.

“There has to be a place where the pendulum stops in the middle and we can do something to protect the contractors while also protecting the people hiring them,” she said. “And it’s the victims who are blamed. This is why people don’t come forward. We want to have a voice.”