Columbia Falls Eyes Resort Tax Possibility to Fund Public Safety

City growth means it will eventually have to transition to a partially paid fire department instead of all volunteer

By Molly Priddy

The city of Columbia Falls has planned a public workshop in late July to look into the idea of becoming a designated resort community, with the power to leverage a resort tax.

That tax would be one of the possible options to begin paying firefighters in the city, said City Manager Susan Nicosia, as Columbia Falls looks at transitioning away from an all-volunteer force.

Last fall, the Columbia Falls City Council decided to ask the state Department of Commerce if the city qualified as a resort community. In April, the council received word that the city did qualify, kicking off the start of the public process for potentially adopting a resort tax.

Under Montana law, there are two types of resort districts: communities and areas. Resort communities are incorporated towns with populations less than 5,500 people, whereas areas would be unincorporated entities with fewer than 2,500 people. The Department of Commerce also looks at other factors when determining if a community qualifies for the resort designation, including economic wellbeing and location.

Resort communities in Montana include Whitefish, Red Lodge, Virginia City, and West Yellowstone, and resort areas are St. Regis, Big Sky, and Seeley Lake.

A resort tax is a local-option sales tax on good and services sold by lodging and camping facilities, restaurants, food-service establishments that aren’t restaurants, public businesses that sell alcohol by the drink, destination recreational facilities, and establishments that sell luxuries.

The rate is set locally, and cannot exceed 3 percent. Also, a minimum of 5 percent of the collected taxes must go toward property-tax abatement in the district.

Now that the city council knows the town qualifies for the designation, the public part of the process is getting under way. There will be a public workshop on July 29 to discuss the possibility of a resort tax and how its proceeds should be spent, which is also under local control.

The town would then have to vote to approve the resort tax via ballot.

For example, in Whitefish, 65 percent of the resort-tax revenue goes toward street improvement projects, 25 percent goes to property-tax abatement, and the remaining 10 percent is divided among contributing businesses and local parks.

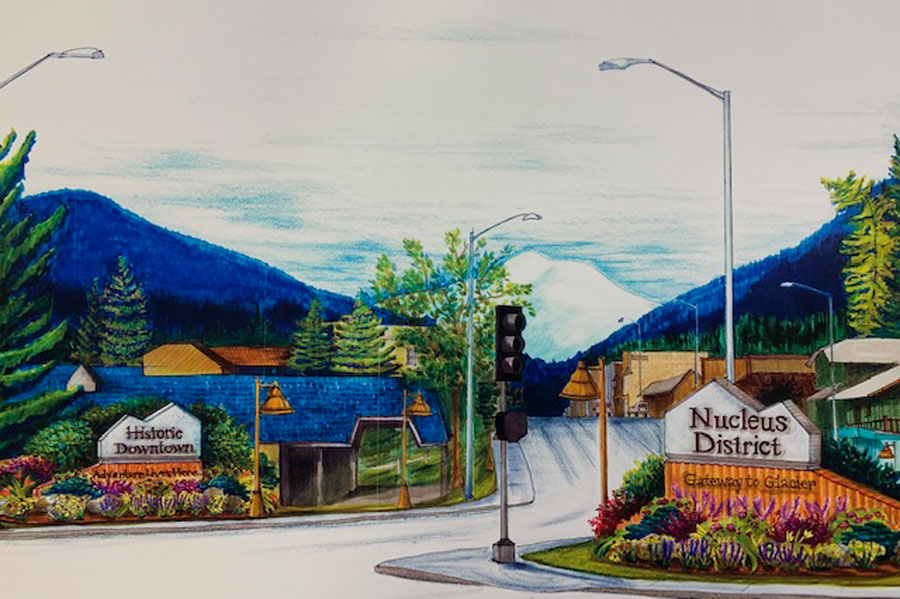

In Columbia Falls, the town’s location near Glacier National Park helps it qualify for resort status, according to the report from the Commerce Department.

“Obviously there’s a strong seasonal correlation in employment and traffic,” Nicosia, the city manager, said. “Look where we live. We’re at the mouth of Glacier Park and Flathead National Forest. We’re a launching point.”

And as the city continues to grow, so do its public safety requirements. Right now, Columbia Falls’ fire department is all volunteer. Cities with populations between 5,000 and 10,000 are considered “second class” in Montana law, which come with more requirements than a third-class city with 1,000 to 5,000 residents. Once a city becomes first class, or has more than 10,000 people, no volunteers are allowed. Second-class cities are allowed to have partially paid departments along with volunteers.

Since Columbia Falls’ population clocked in at 4,688 in the 2010 census, Nicosia said the city has started preparing to transition to a partially paid fire department.

And as more people move into Columbia Falls, it’s important to have a fire department that can consistently respond during the day, Nicosia said, as opposed to relying on volunteers’ ability to respond, due to myriad factors like being out of the valley for work or vacation.

“We have an outstanding volunteer fire department,” Nicosia said. “One of the problems that we have is getting a response during the day.”

The city council wanted to look at all options for paying for this transition, Nicosia said, instead of just relying on a ballot levy and increasing property taxes.

“We’re putting together short- and long-range plans of how do we address this and where does the funding come from,” Nicosia said.