LIBBY — Julius Neils was a man in search of a home, and this was a place in search of an identity.

In the early 20th century, the logging magnate had aggressively clear-cut through the forests near Cass Lake, Minnesota and nearly grounded the J. Neils Lumber Co., burning too quickly through the most vital resource in his moneymaking operation. So Neils and his family moved west, determined not to repeat the mistakes of the past and to goose the profits of the family business.

Libby was a town of just a few hundred people when the newcomers from Minnesota acquired an existing logging operation around 1910, and Neils almost immediately devoted himself to his new community, securing the company’s long-term viability by nurturing the town’s steady growth. In 1929, when the stock market crashed and the Great Depression began, Neils kept his timber operation running, albeit at vastly reduced hours, to keep as many people employed as he could and to keep the city from evaporating beneath him.

By the end of World War II, Libby had come out of the Depression and was booming like much of the rest of the country. Neils died in 1933, but his offspring stayed true to his original vision and became early adopters of what was then a revolutionary policy of sustainable yields, developed in conjunction with local forest managers. The town enjoyed a healthy symbiosis, with the loggers harvesting only as much timber as the mills could saw and the forest could sustainably allow.

According to the local folklore, Libby did not need anything or anyone else. The town is naturally isolated, a land-locked island in the forests of Lincoln County, 90 miles from the nearest moderately sized city (Kalispell) and separated from there by almost nothing but wilderness, even today. Libby’s unavoidable insularity has created a powerful community bond that still persists, forged in the days when neighbors became fast friends, sometimes only because no other options were available, and tightened through the harmonious relationship between blue-collar workers, a civic-minded employer and the warmth of personal stability. There has always been tremendous city pride in Libby, created at a time when everything and everyone worked together.

“There was a sense that if we do things right here, it’s going to work, we’re going to make it work,” Jeff Gruber, Libby’s unofficial historian and a former high school teacher, says. “Then you talk about a town turning upside down — that’s Libby.”

The distinct revving of chainsaws fills the fall air on a November afternoon, a sure sign that Libby High School’s football team is in action. The stands are full, the players clad in their distinctive blues and the chainsaw operators, younger even than the combatants on the gridiron, place their oversized instruments on the ground until the Loggers, the nickname of most of the school’s sports teams, put points on the board.

That a game is even happening at Logger Stadium in November is itself noteworthy. Libby is in the Montana High School Association playoffs for the first time since 2011, and the intervening seven years were bleak. The Loggers endured almost two straight years without a win during that stretch and did not post better than a .500 record until 2018, when they narrowly missed qualifying for the state playoffs. Still, on Friday nights the town of 2,500 or so people would mostly fill the stands and the chainsaws still rumbled, even without many scores to celebrate.

“We were getting beat 50-0, 56-0, and if we had two or three plays a game that were positive, that was good; you were looking for anything to hang onto,” Neil Fuller, Libby’s head football coach, said.

Fuller brought his two sons to Libby in 2003, at a time when a lot of people were doing the opposite. The first hints of Libby’s exposure to deadly asbestos from the W.R. Grace and Company vermiculite mine came in the 1980s, but in 1999 an explosive news story that gained national attention revealed the extent to which the town had been affected. Hundreds of people died, thousands more were sickened, the town became an Environmental Protection Agency Superfund site — a designation given to locations in need of long-term environmental cleanup — and Libby was left reeling. The town that relied on itself had been poisoned from the inside.

But Libby’s downward spiral had been deepening years before the truth about the mine came out. The J. Neils Lumber Co. merged with the St. Regis Paper Co. in 1957, and then sold to a larger operation, Champion International, in 1984. The profit-motivated outfit with no roots in Libby left when money became harder to make, and a new operator later separated the logging and mill operations, ending the symbiotic relationship they had long enjoyed. The mill was closed in 2002.

The W.R. Grace mine, once a large part of the local economy, was itself down to just about 100 employees by the time it was shuttered in 1990, and a mini-boom that accompanied the construction of the Libby Dam in the 1960s and 1970s had dissipated once the dam was complete and mercenary workers moved on.

This was the town that Fuller came to in 2003, in search of a new coaching job after becoming disillusioned with his situation at Douglas High School in Winston, Oregon. Fuller, a Shelby, Montana native, pulled into a Libby motel ahead of his interview and thought, “What in the world am I doing?” Then he fell in love with the town and its people.

“It’s the best place I’ve ever lived,” he says. “Having (my sons) grow up here and develop the friendships they did and have the teachers they did, it was just the perfect move for us.”

George Mercer played on Fuller’s first team in 2003 and was part of a sustained run of success to start the new coach’s tenure. The Loggers hosted home playoff games every year from 2003-07 and reached the state semifinals in 2004, 2006 and 2007. In 2004, Fuller’s second season, a handful of his players’ dads surreptitiously brought Libby-style noisemakers to a quarterfinal game in Sidney and revved up their chainsaws to the startled horror of the home crowd after the Loggers won.

Mercer went from Libby to the University of Montana, where he was a valuable defensive end on teams that made it to the national championship game in 2008 and 2009. He is the branch manager at the Glacier Bank in town these days and, like most of the rest of the town, follows Loggers football closely.

“Everybody knows about the games, the scores, the players,” he said. “You get to a Friday night, there is nothing on Facebook but straight football talk … People around me who aren’t even football fans, they know who our starting quarterback is.”

Terry Maki Jr. is among the greatest athletes to ever attend Libby High School. The 1982 graduate was a two-time state champion wrestler and standout football player before he walked on at the U.S. Air Force Academy in Colorado. At Air Force, Maki enjoyed a legendary two-sport career, graduating as the program’s all-time, single-season and single-game record-holder in tackles, according to a 2009 Denver Post profile, along with a pair of Western Athletic Conference wrestling titles. Maki later went on to a decorated career in the Air Force before retiring in 2006.

Maki’s father, Terry Sr., was born in Columbus, Montana and joined the Air Force to “see the world.” Instead, the government sent him to a remote radar station on Hensley Hill in Yaak, just outside Libby. The elder Maki met a girl in town, a third-generation Libby-ite named Jeannette, and they eventually raised their family in town, with Maki Sr. working on radio communications for, among other places, the W.R. Grace mine.

“It just seemed like everybody had jobs and everybody had money,” Maki Jr. said of his childhood. “It just seemed like a thriving community with a lot of community pride back then.”

Jeannette Maki still lives in Libby, and her son comes up to visit as often as he can. But he was mostly deployed overseas when the worst of the downturn struck in the 1990s and 2000s.

“I don’t know if I’ve fully processed it yet, even,” Maki Jr. said. “It’s overwhelming to see changes and how it changed the entire face of the community.”

The Maki family did not escape unscathed either. Terry Sr. died of an asbestos-related autoimmune disease, and Jeannette and one of her daughters have also suffered from related illnesses, Maki Jr. said.

The younger Maki moved to the Bitterroot once his Air Force career was over and jumped right back into football, coaching at Florence-Carlton High School for a bit, and he, like Mercer, is an avid follower of his hometown team. He watched with admiration as the Loggers won eight times during the 2019 season.

“I’m so proud inside to see it,” he said. “That can change things drastically for a community to have success like that.”

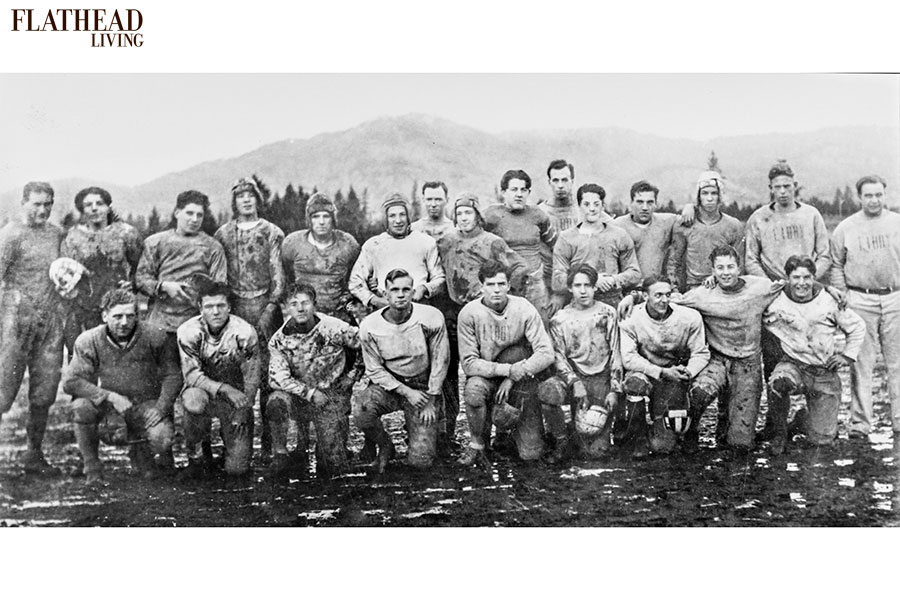

Only two teams from Libby have ever won a state football championship. The 1932 team, then known as the Terriers, was so segregated from the rest of Montana that they rode trains to get to almost all of their road games, even in places as close as Kalispell. They beat Poplar 18-0 to win the state title and were honored by the local Lions Club with a Depression-era banquet of roast venison to celebrate.

Three decades later, the well-to-do denizens of town, buoyed by the construction of Libby Dam, pooled their money and lured legendary coach Frank Little from Kalispell to lead the team. The Loggers, renamed so in 1953, beat Glasgow 26-7 to win the 1967 state title.

The 2019 Loggers would not join that list. They were wiped out by Laurel in the state quarterfinals but not before giving their hometown fans a thrill on Nov. 2 when they beat Butte Central Catholic 49-28. Fuller said he “had more fun coaching this year than I have in years,” and his team fought through its own share of adversity, playing the entire postseason without injured starting quarterback Jeff Offenbecher and leaning on a blue-collar power rushing attack and opportunistic defense.

After the game against Butte Central, the revving chainsaws (sans chains, of course) formed a makeshift tunnel for the players to run through, and the crowd of fans, friends and family in the stands eagerly met the victorious boys in the parking lot behind the school to celebrate as one. A few people lingered a little longer back in the bleachers, soaking in the weightless air as the roar of a playoff crowd gave way to quiet tranquility.

In this moment, a man in Libby gear in the front row leaned over the railing, located a familiar face and said, with a smile, “So that’s what this looks like.”

Read more of our best long-form journalism in Flathead Living. Pick up the winter edition for free on newsstands across the valley, or check it out online at flatheadliving.com.