Public Health Officials Take Aim at County Leaders for Failure to Act on COVID-19

Chair of board of health calls for removal of Dr. Annie Bukacek, warns that more deaths are coming; deputy health officer says department ‘standing alone’

By Andy Viano

The Flathead County Commission and Flathead City-County Board of Health have repeatedly declined to enact any restrictions to limit the spread of the virus and to provide relief or material support to the health department’s beleaguered staff, even as the numbers of COVID-19 cases in the county have reached unprecedented highs in the last month-plus.

The only way that will change, according to the board’s exasperated chairman, is when “more people die.”

Bill Burg, a retired U.S. Marine and the chair of the board of health, and Deputy Health Officer Kerry Nuckles described feelings of helplessness, frustration and fear in separate interviews with the Beacon this week, chronicling a series of blows to the health department and the safety of the community that they say fall squarely at the feet of the county’s three elected commissioners and the eight-member board of health that the commissioners are largely responsible for appointing.

“We are going to have to live with it unless we can sway the vote of the board of health,” Burg said of the illness, long-lasting complications and death that can be caused by COVID-19. “The data in front of us says you have to do something or you are personally responsible. It’s going to be a tough road.”

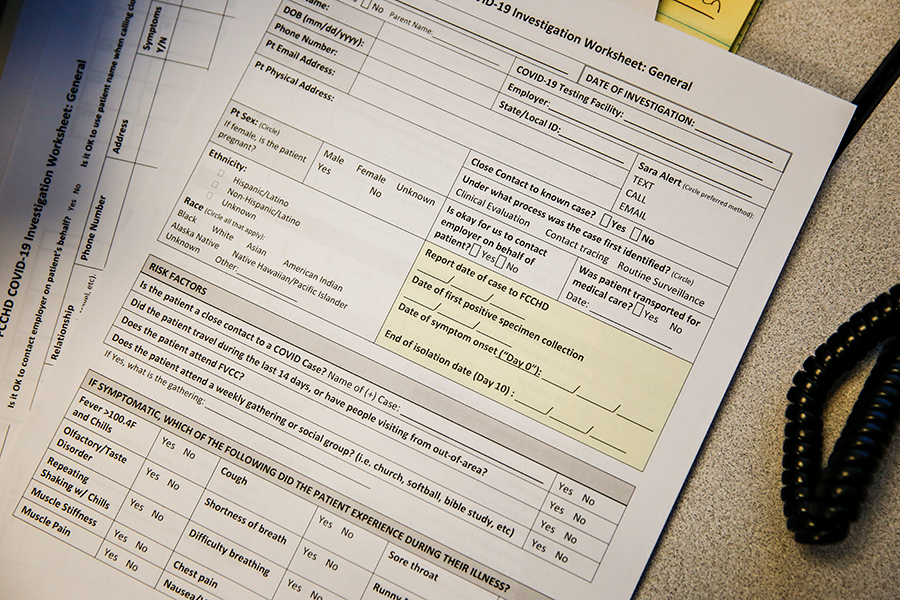

Officials from Washington D.C. to Helena down to the Flathead City-County Health Department have, for more than a month, pointed specifically to Flathead County as a COVID-19 hot spot. The county reported 2,217 new cases in October, and so far November has been worse. After three straight days of 100-plus new cases, Nuckles said she expected at least 200 more on Friday. The health department said on Thursday it had abandoned contact tracing except for high-risk contacts, and with case investigations sometimes starting two days after a positive test, the effectiveness of those efforts was already limited.

In spite of that, the county has dismissed the recommendations of health experts, and the health board has voted down even modest proposals from the health officer to limit the size of public gatherings. In the last month, the county commission has come out in support of residents who refuse to wear masks in public, the county attorney has declined to prosecute any businesses that violate directives from the governor’s office, questioning their legality, and law enforcement has said it is unable to enforce widespread mask violations.

“With the commissioners saying they’re not doing anything, the police saying they’re not doing anything, and the county attorney didn’t say he would do nothing but he said we’ll probably lose, there aren’t many people standing with the health department,” Burg said.

The board of health is supposed to be the one entity that does stand with public health, but a division among members has put four on each side and the two sides in seemingly intractable positions. The board is supposed to have nine members, but the ninth is Tamalee St. James Robinson, who was appointed interim health officer earlier this year when Hillary Hanson resigned her post, and her board position hasn’t been filled. The even number means that five of the eight members must vote in support of any motion for it to pass.

The board’s most recent decision fell 4-4 at an emergency meeting on Nov. 2 when Dr. Annie Bukacek, County Commissioner Pam Holmquist, Ardis Larsen and Ronalee Skees voted against a proposal that would have limited gatherings to 500 or fewer people. Burg, Dr. Peter Heyboer, Roger Noble and Kalispell City Councilor Kyle Waterman voted in favor.

“The four don’t want to have progress,” Burg said. “The evidence is stronger than it was, and I thought that would sway people but it didn’t, and it doesn’t, and that’s disturbing. It appears that whatever is motivating the other people is not the interest of public health. It’s something else.”

Part of the argument opponents make is that public health officials focus too much on case numbers and, in their opinion, not enough on deaths and hospitalizations. As of Nov. 5, 27 Flathead County residents had died of COVID-19 and 28 people were hospitalized in the county.

Nuckles and other health experts, though, say looking only at deaths and hospitalizations wrongly dismisses an entire group of people who have to deal with the short- and long-term consequences of the illness.

“Deaths are the tip of the iceberg,” Nuckles said. “For every person that dies you have more people who will have long-term illnesses, who will have multi-organ damage from this disease, who will have respiratory problems for a long period of time.”

“Down below that are people who are really sick for a really long time, who can’t go to work, whose kids can’t go to school. And then you get the mild illnesses … It’s great if you’re not sick but just because one person doesn’t get really sick doesn’t mean the next person’s not going to have truly severe health symptoms that will last for a long time.”

The other most common argument among opponents of mask mandates and other opponents, including some board of health members, is that such regulations violate Constitutional freedoms. Bukacek, an anti-vaccine and anti-abortion advocate who has organized local anti-mask protests and spoken at the church of pastor Chuck Baldwin, has questioned the seriousness of COVID-19 and been contemptuous of government restrictions. Her arguments at board meetings cite dubious science, and when she rounded statistics up at an October board meeting to falsely declare the COVID-19 survival rate was 100%, the county’s preeminent infectious disease doctor abruptly hung up on the Zoom teleconference.

In pushing back against those fearful that their freedoms are being infringed, Burg quoted an oft-used retort from politicians in times of crisis, that “the Constitution is not a suicide pact.”

“We still regulate traffic and we still regulate smoking and drinking, and a lot of other things in the public interest, primarily for the potential damage to others,” Burg continued. “I’ve not had anybody come back and make the assertion that their rights to infect other people should go unrestrained.”

Bukacek and Larsen, who performs field work and inspections for an engineering firm, were appointed to the board of health last December when two long-serving physicians, then-chair Dr. David Myerowitz and then-vice chair Dr. Wayne Miller were booted from the board by the county commission. Myerowitz was sharply critical of the decision at the time, calling the appointment of Bukacek “unconscionable,” and Miller was equally blunt in his assessment.

“We are being replaced with two people who are, without question, not qualified to sit on this board,” he said.

Nuckles is an epidemiologist, and from her post she too has grown dismayed at the way Bukacek and other members of the health board have dismissed the consensus understanding of the coronavirus shared by reputable medical professionals.

“It’s hard when I come with research and I come with studies and statistics, and we talk through how tests work and how we’re using the numbers, and it falls on deaf ears,” she said.

“We had 140 doctors sign a petition saying masks are effective and we have one doctor [Bukacek] say they’re not effective, and the takeaway, in my opinion, from the board and commissioners is, well, there’s two sides to every story. There’s not two sides to every story. You don’t get to make up your own science.”

Nuckles said she has worried about the two new health board members since their appointments, which came before the start of the pandemic, saying appointees should have an “expertise” in public health in order to serve on a board tasked with preserving the public’s health.

“It’s frustrating when we talk about restrictions and we talk about the trajectory of the epidemic and we have board members say, ‘Well, I don’t understand, I can’t make a decision, I don’t have enough information or I don’t have enough knowledge to make that kind of decision,’” she said. “That’s the role of the board of health.”

Burg specifically called for Bukacek to be removed from the board, calling her beliefs “so far out of the mainstream” that they are incompatible with such a position. Such a move could be made by the county commissioners but would require two of the three to support the action, something they have thus far been unwilling to consider.

“Annie has shown that she doesn’t believe in public health,” Burg said.

In an email, Bukacek did not respond directly to Burg’s suggestion that she be removed but wrote that “diversity on a board is not just a good thing, it is necessary.”

Inside the health department morale is continuing to sag. The public defiance of recommendations and restrictions has long been a source of disappointment, but with local leaders now part of the opposition those feelings have deepened. And then there is the realization that with winter around the corner and no new restrictions apparently on the horizon, the situation on the ground could get much worse.

“I like to think the Flathead is better than (this). I like to think that people care about their neighbors and want to do the right thing,” Nuckles said. “And I want to do everything we can to prevent this community from getting to that point where we have refrigerated morgue trucks, but I don’t know.”

The frustrations of Nuckles and Burg extended to the three-member county commission itself after an Oct. 29 meeting. At that meeting, the health department brought forward a months-in-the-making proposal for purchasing a mobile care unit that Nuckles said is vital for the deployment of a forthcoming COVID-19 vaccine, and asked the commissioners to authorize overtime pay for exempt (non-hourly) employees who have been working 70-plus hours per week since March and are unable to take their earned compensatory time. Burg supported both moves. The county commissioners denied each one, rejecting the mobile unit over concerns that it may not fully qualify for federal CARES Act relief funds.

In denying the overtime request, Commissioners Phil Mitchell and Randy Brodehl (Holmquist was absent from the meeting) put forward an argument about the possible illegality of such an action without evidence that it would have been illegal. Nuckles said the move would not violate the Fair Labor Standards Act cited by the commissioners, and that similar overtime pay was supported in other jurisdictions and approved by the Montana Association of Counties (MACO). The commissioners’ argument was further undercut by an acknowledgement that the county had approved a similar proposal for emergency responders during a recent wildfire season.

At the Oct. 29 meeting, Mitchell cited “philosophical problems” he had with the request for overtime. In an interview on Friday, Mitchell said approving the request would be unfair to other exempt employees who also sometimes work overtime, and he questioned why the health department has been unable to fill open positions that could reduce the strain on the staff.

“If you don’t manage your time well, Kerry Nuckles, that’s not my problem,” he said. “The other way to solve this, health department, is hire your people. You have CARES money for anybody you want to hire. You could hire 20 people, 50 people tomorrow. The answer will be, ‘We can’t find people.’ I disagree. Find some more people to work.”

The department currently has more than 30 temporary employees assisting with contact tracing.

“It’s hard enough to get denied for overtime when you’re asking for help, it’s another thing to be insulted and belittled, and that’s par for the course,” Nuckles said.

Burg was similarly critical of the commission and took aim at Mitchell, walking back a more direct insult to call the commissioner the “north end of a southbound horse.” Mitchell responded by calling Burg “a problem” and accusing him of supplying inaccurate data to the commission.

“It’s disturbing,” Burg said. “The county spends a lot of money on public health and (Mitchell)’s making it more challenging for these people to monitor public health.”

The continued pressure and lack of support for public health officials has been felt in other communities around the state as well, and it boiled over in Pondera County on Wednesday, when the county’s entire health department resigned. Asked about that news, Nuckles said she loved the work she was doing and the people within the health department, and reiterated a commitment to stay in her position despite the obstacles.

“We have a 9 a.m. meeting every morning and I can’t bring myself to go to that meeting and tell them that I’m leaving them,” she said. “And that’s the only reason I’m still here.”

Nuckles tells those co-workers not to watch the board of health meetings, and Burg said he had an employee come up to him in tears after one recent meeting, telling him “nobody else cares” about the work they were doing.

“Please pass around that we do care,” Burg said this week. “Just not enough of us.”

For Nuckles and the rest of the health department staff, support from enough people on the health board feels like a pipe dream. They just hope the board doesn’t drown them in the challenging months to come, a possibility that a co-worker shared with Nuckles in vivid terms.

“(They) said, ‘It feels like we’re standing together on a sinking boat and we’re bailing as fast we can, and the board of health has a hose aimed at the deck of the boat, filling it up with water,’” Nuckles recalled.

That’s when another employee, eavesdropping on the conversation, chimed in.

“No, it’s not a hose,” the employee said. “It’s a fire hose.”

UPDATE (Nov. 7, 3 p.m.): This story has been updated to include a brief comment from Dr. Annie Bukacek.