Trust in Walking

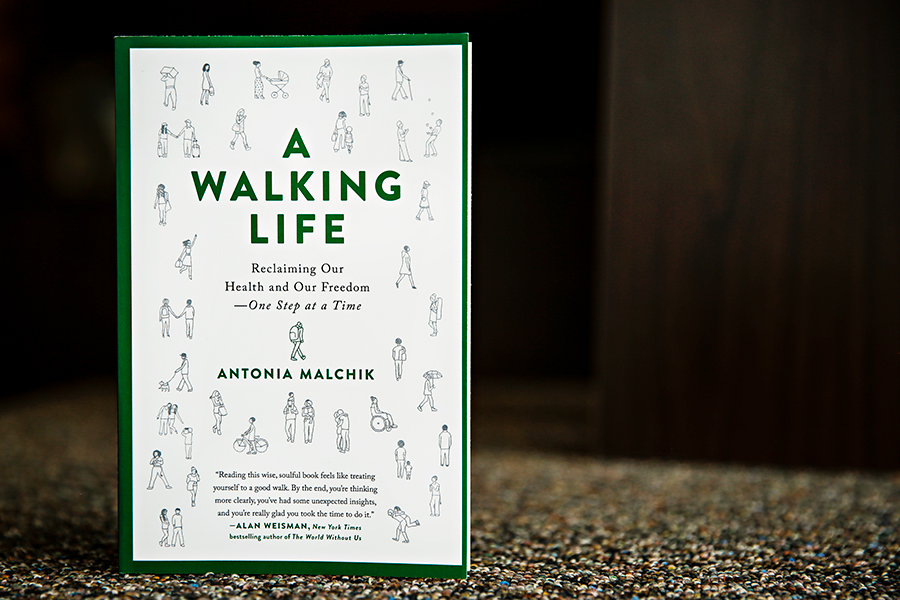

Local author Antonia Malchik published her first book ‘A Walking Life’ last year, emphasizing the relationship between walking and communities

By Maggie Dresser

Before Antonia Malchik moved her family back to Whitefish six years ago, she was living in a cookie-cutter house in upstate New York on a former farm field. Her driveway intersected with a busy road with no shoulder or sidewalk, making it impossible to safely take her kids for a stroll without getting into a car to drive somewhere first.

Prior to having kids, Malchik wouldn’t have thought much about this inconvenience, but as a mom who was trying to get her kids out of the house, while staying close to home, it seemed a bit strange.

“Suddenly I was in a life where if my car wasn’t working or if I was snowed in, I would be stuck,” Malchik said. “You should be able to walk to a store or to services or to the library or a playground, and we couldn’t do anything.”

That realization led Malchik down a walking rabbit hole, researching everything from how Americans have lost walking access to the science and evolution behind humans’ physical capabilities of moving on two feet. After publishing a few essays focused on walking, she went further in depth, writing “A Walking Life,” her debut book exploring the relationship between walking, humanity and communities.

Published in 2019, “A Walking Life” travels back six million years ago to the oldest fossil ever to show upright walking. While experts don’t know much else about that early human species, they say it’s been a very long evolution.

“Nobody knows why we walk on two legs,” Malchik said. “Every step you take, your brain makes a billion calculations because it’s so difficult and complex to take a step forward.”

But the crux of the book is the relationship between walkability and communities. Malchik argues that walkability correlates with trust within communities, resulting in lower crime and better health and resiliency. Since Malchik says humans are innately more community-minded than competitive, we rely on each other because walking makes us vulnerable.

“In a way, people had to be able to trust one another and rely on one another for help,” Malchik said. “For example, if you’re picking fruit and you’re a mother, you need to hand someone your baby. With monkeys, their babies can cling from a very early age and human babies can’t do that.”

But this dependence became less important once the automobile emerged in the early 1900s. Cars started taking over the streets, which limited our access to walking and led to automobile-related deaths.

“People hated cars,” Malchik said. “They called them murderers and death machines.”

Malchik says there was a massive campaign to eliminate cars from cities, but the automobile industry won in the end, resulting in roads that would further separate and divide communities.

While vehicles have evolved to become a part of society’s norm, communities are now trying to reverse some of driving’s negative and unintended consequences by creating more walkable communities and allowing more accessibility to nature.

Last fall, Malchik served as a keynote speaker at the Business of Outdoor Recreation Summit Recreation Innovation Lab in Whitefish, which focused on sharing “innovative community-driven approaches to creating, protecting and enhancing front-country outdoor recreation access close to home.” The summit’s purpose was to brainstorm ideas on how to make communities, like Whitefish, more accessible.

“I loved that they were doing that because it’s really important,” Malchik said. “That is how you make a connected community because you need walking and nature accessible for everybody. You don’t have to have a backpack or necessarily drive to do that.”

This past spring, while the economy was shut down, Malchik started to notice that while Whitefish is a walkable city, most of the sidewalks and paths lead only to commerce.

“I love our downtown and Whitefish had done a good job making it walkable, but it makes me think of the uses of that space,” Malchick said. “You could connect different trails through downtown not just for cars. People would still be walking even if they couldn’t go shopping or go to the library or go get coffee. It does feel like a big waste when you realize that’s a lot of space to give just to those particular uses.”

The age of social distancing has also interfered with community interactions, Malchick says. Even though there seems to be more people outside since the pandemic began, trying to stay six feet apart from others while wearing a mask doesn’t make connections easy.

“My whole thing about community is you have to see stranger’s faces,” she said. “And you have to interact with people who are different than you … You build trust by interacting with people.”

For more information, visit www.antoniamalchik.com.

Read more of our best long-form journalism in Flathead Living. Pick up the fall edition for free on newsstands around the valley.