One by one, they poured their hearts out at the Flathead High School auditorium, some spitting mad and others on the verge of tears. They were as young as elementary-school students and as old as grandparents. They sat on opposite sides, for the most part, absorbing every impassioned plea and erupting in applause when one matched their particular point of view.

It was what almost everyone expected as the Kalispell school district prepared to hear from its community, a move that officials didn’t have to make but did anyway, for the purposes of letting everyone say their piece. And plenty was said, some of it expert opinion, some of it dubious science, and all of it emotional. When it comes to kids, it almost always is.

In the end, a little after 10 p.m. and more than four hours after the single-issue Feb. 24 meeting began, the Kalispell Public Schools board voted unanimously, 11-0, to keep the district’s mask requirement in place.

But what was lost on that supercharged Wednesday night was how remarkable it was that the debate was even happening. It came less than a week after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) put out its first recommendations on how to safely reopen schools, not long after President Joe Biden released his own “roadmap,” and as districts from coast to coast grapple with how to open the doors to school buildings without inviting a COVID-19 super-spreader event.

How to reopen schools? A “roadmap” to five-day-a-week in-person learning? In the Flathead Valley, that’s a road already well traveled. Buildings have been open and school has been in session for almost every student who has wanted it in Northwest Montana for the entire 2020-21 school year.

Last summer, the same fear and skepticism being felt around the country was very much on display here, but, to the surprise of some and thanks to the efforts of many, this unusual school year has gone more smoothly than even some superintendents expected. Health officials say tight COVID-19 mitigation measures, not least of which was requiring and strictly enforcing a mask mandate, have made buildings safe, and as the rest of the country looks to catch up it’s worth examining just why things have gone so well, what it means for the young people who have spent this year in school, and just what’s at stake if safety precautions are rolled back.

How to Do It

Former Gov. Steve Bullock ordered an end to all in-person instruction in Montana on March 15 last year and sent schools frantically trying to figure out how to conduct class through a computer screen.

The results were a mixed bag. If teachers could even get their students to show up for Zoom school, the level of rigor dropped precipitously, and by June it was obvious that a better plan was needed in the fall.

So when administrators huddled with public health officials to figure out what the 2020-21 school year was going to look like, one of their most important tasks was finding a way to get teachers and students safely back together, in person.

“I said, ‘I may be wrong but my hunch is we need to be as routine and normal as possible,’” Kalispell Public Schools Superintendent Micah Hill said. “There was certainly some feedback from teachers and administrators and the community about whether that was the right decision.”

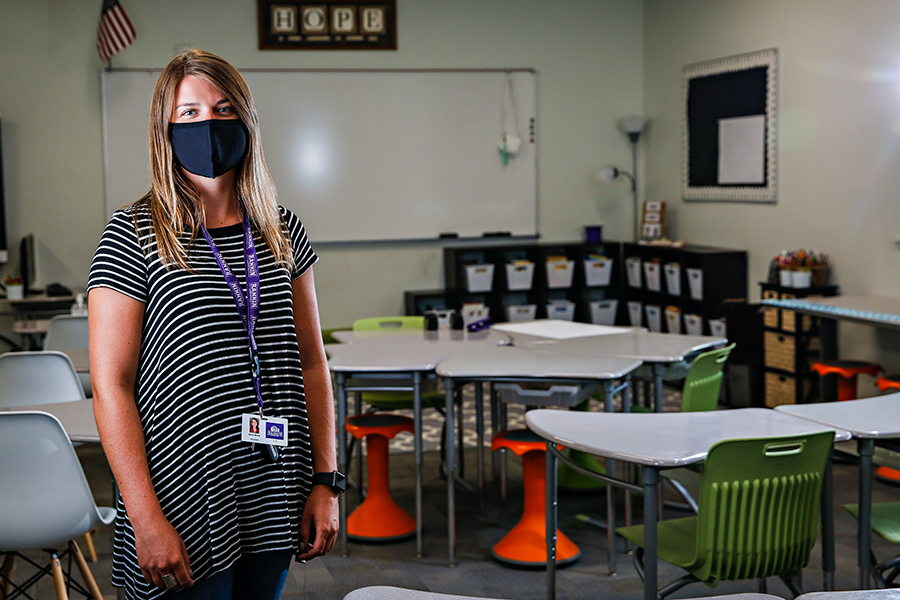

The decision, cheered by a large number of parents desperate for a return to a more normal routine and derided by some educators as a reckless move made without regard to their health and safety, came with a number of additional mitigation measures. A remote option would still be available for students and teachers with underlying health conditions or who otherwise felt unsafe in cramped school buildings. Major sanitization and cleaning protocols were implemented. Extracurricular activities were altered or paused altogether. And everyone had to wear a mask.

Local superintendents spent hours together in an effort to be comprehensive and somewhat unified, and Evergreen School District Superintendent Laurie Barron called the process “intentional,” “cautious” and “well thought out.” But even she had her doubts.

“It didn’t feel haphazard or that we were just throwing something together,” Barron said. “But I still had this gut feeling that I wasn’t sure it would work … Every week I felt like, ‘What if this is the week we can’t stay open?’”

Barron wasn’t the only superintendent who seemed to be bracing for the worst from the day school opened in August. Particularly in those early months, and as COVID-19 cases reached record levels in late fall, schools were regularly teetering on the edge of having to shut down, something that did briefly happen in a few Northwest Montana districts.

While there was very little documented in-school spread of COVID-19, teachers and students were still routinely impacted as the virus spread in the community. Staff absences, either due to infection or required quarantines, regularly left schools undermanned, and a dearth of substitute teachers meant paraprofessionals, administrators and even teachers on their planning periods had to pitch in and cover for their colleagues.

That attitude, administrators say, is a key factor on the road to reopening. Every superintendent interviewed for this story heaped praise on their staff, saying a willingness to adapt on the fly, work extra hours, and in some cases learn how to do their job in an entirely new way is what kept the doors open.

Teachers sometimes had the unusual experience of waking up to discover that a handful — or several handfuls — of students in their classroom were suddenly quarantined and had to adjust lessons for either remote or synchronous learning, while others taught in fully remote academies like the one set up in Kalispell for students who chose to stay home. Teachers also had to reintegrate some students back into the classroom as most districts report that a number of kids who started the year either learning remotely or being homeschooled have re-enrolled for in-person instruction.

“We can put all the plans and things in place, but those day-to-day decisions and operations within the classroom, it took the teachers and the staff and they really stepped up,” Hill said.

“Everyone has done a great job,” Whitefish Superintendent Dave Means said. “The parents, the students following protocols, (and) our staff has been very creative and resilient in their efforts to support students. I really am impressed how it has gone throughout the year.”

There were other important pieces, too. Schools adapted quickly as they learned more about COVID-19, creating procedures for lunch, recess, busing and even hallway traffic, and staffing up on substitutes. Barron in particular also credited federal funding that allowed her district to hire additional custodial and office staff.

And then there is what school and public health officials point to as probably the single biggest factor: masks. As more and more of the public got sick of wearing them and the debate over masking turned into one of the most explosive political hot buttons of the year, schools were a zero-tolerance zone. Masks were required to be worn, properly, at all times. And it worked.

“It’s working exactly the way we would anticipate it,” Flathead City-County Health Officer Joe Russell said. “When all of these CDC (recommendations) are coming out, they’re basically coming out and stating the same things we’ve been facing all year.”

As the calendar turns to March, superintendents in those districts that have retained mask mandates are optimistic about the remainder of the year. Hill said he would be “hard-pressed” to imagine a scenario wherein his district didn’t reach the end of the school year in person, and even Barron, who kept holding her breath waiting for the day when COVID quarantines left her school short-staffed, is ready to declare victory.

“What we’re doing is not just impressive,” she said. “It’s safe and it’s healthy and it’s good for kids.”

What It’s Meant

Years from now, a time will come when the world reckons with COVID-19’s legacy and what it’s meant to the young people who lived through it. It’s logical to assume that students have suffered because of remote learning, and there is even some data to back up the phenomenon, which even has a name: the COVID slide.

“We brought in every elementary kid (after the spring shutdown) and had them assessed,” Bigfork Superintendent Matt Jensen said. “And our data was really bad.”

The encouraging thing for students in Northwest Montana is that in most places, including Bigfork, those test scores have rebounded since most students and teachers returned to the classroom. Means said students are “improving significantly” in Whitefish, and in Kalispell, Hill looked forward to being able to compare how well his students were doing to the rest of the country.

“I think being in school every day is making a difference,” Hill said. “I’m excited to actually see where things play out.”

Perhaps as important as the effect of in-person instruction on education is the value of the school setting, both as a service provider and in social-emotional development. School counselors were concerned last year about the mental health of students suddenly cut off from resources, districts scrambled to provide meals for the boys and girls who depend on them for breakfast and lunch every weekday, and advocates worried that abuse cases would go unreported with kids kept away from mandatory reporters, like teachers.

The benefit of a return to school buildings is difficult to quantify but not hard to observe.

“You cannot overstate the importance of social interaction with peers,” Barron said. “It’s not just about on-site learning … for kids to be able to have socialization and athletics and music and art, it’s critical.”

As the year has gone on, more and more extracurricular activities have returned as well, and districts have started loosening restrictions on crowds at sporting events and concerts, albeit with strict mask requirements still in place. It’s an opportunity that hasn’t been available to countless students across the country.

“We’ve just been fortunate,” Hill said. “We argue over masks and then we lose sight of all the other opportunities that exist.”

What’s at Stake

Despite all of the good vibes, as Hill can attest, there is still the issue of the masks.

Kalispell’s raucous school board meeting is behind him, but Hill was still being inundated days later by parents furious about the board’s decision, and what they see as Hill’s complicity in the decision. But you don’t have to look far down the road to see that a superintendent’s recommendation only goes so far.

Jensen, who in addition to being Bigfork’s superintendent is the head of the Northwest Montana Association of School Superintendents, recommended that the Bigfork Board of Trustees keep a mask mandate in place at a meeting last month, after newly elected Gov. Greg Gianforte repealed the statewide mask mandate. Bigfork’s board voted against Jensen and the mandate, 4-3, and masks will be optional in Bigfork schools beginning March 15.

Jensen and the three principals of the district’s schools — all of whom also recommended the board retain its mask mandate — are still working to figure out what an unmasked school will look like, but there is a general consensus among public health officials that it won’t be as safe as it has been. Even if some students and teachers continue to wear masks, they are most effective when everyone is wearing one since the mask stops viral droplets from escaping far from your mouth or nose.

“The best thing we can do, if we want to keep those schools open, is mask use, and mask use is by far best when the two people that are in contact are both masked,” Russell, the county health officer, said. “That’s why it’s working. It works because we have masks on everyone.”

In Bigfork, however, there is a strong sense of disappointment among those who supported the mask mandate, and not just at the school trustees. Jessica Martinz, one of the trustees who supported masking, said the decision never should have been up to them, and Jensen agrees.

“The (county board of health) exists to make public health decisions … and we encouraged them to take quick and decisive action,” Jensen said. “They abdicated that responsibility and then this started to play out … I don’t quite follow their rationale for not making a decision.”

As it happened, the Flathead City-County Board of Health held its monthly meeting on Feb. 18, one day after the Bigfork school board made its decision. The issue came up during both public comment and from some board of health members, but the board did not propose a school directive on masks, a move that is within its power.

The board of health could take up the issue at a future date, but that is not expected.

So Bigfork will plot its way forward, and Jensen will be tasked once again with trying to steer his team through uncharted waters. And no matter what happens from March 15 on in Bigfork, he’s still eager to acknowledge everything that has gone right so far.

“I think all of us in education want to be part of something special, we want to be part of a team and doing the things we do for kids,” Jensen said. “That work’s really rewarding and to see these kinds of results is something (we) should be proud of.”