On the Road to a Record Year

As Glacier National Park braces for what experts anticipate may be the busiest summer on record, administrators are introducing new tools to navigate a complex set of challenges

On a weekly basis since February, in video-conferencing conclaves with chambers of commerce, tourism bureaus and gateway communities girding Glacier National Park, Superintendent Jeff Mow has performed the unenviable task of describing a “confluence of circumstances” he predicts will beset the Flathead Valley with an exacting set of challenges this summer.

“There is no crystal ball to predict the acute nature of 2021,” Mow has said repeatedly. “But all indicators point to a very, very busy season.”

“Very busy as in record-setting visitation,” he added, sharpening his point for clarity during a recent meeting with local stakeholders, all of them reliant in one way or another on the throngs of tourists drawn here by Glacier National Park, and all of them aware of the challenges associated with overcrowding.

Mow’s counterparts in Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks are likewise bracing for record-breaking crowds this summer, and are calibrating their operations in accordance with forecasts for a high, pent-up volume of travel demand in 2021, the logistical challenges of which will be compounded by ongoing COVID-19 mitigations and staffing shortages.

But record-breaking crowds in Glacier Park look and feel different than record-breaking crowds in almost any other unit of the National Park Service, due in part to Glacier’s unique geography, with a single narrow artery traversing the Crown of the Continent’s entire million-acre footprint, and in part to its constrictive seasonal window for summer visitation.

“Our biggest challenge in terms of managing so many people who want to come see this landscape is that we have such a short concentrated season,” Mow said. “That gives us one of the sharpest visitation curves in the system.”

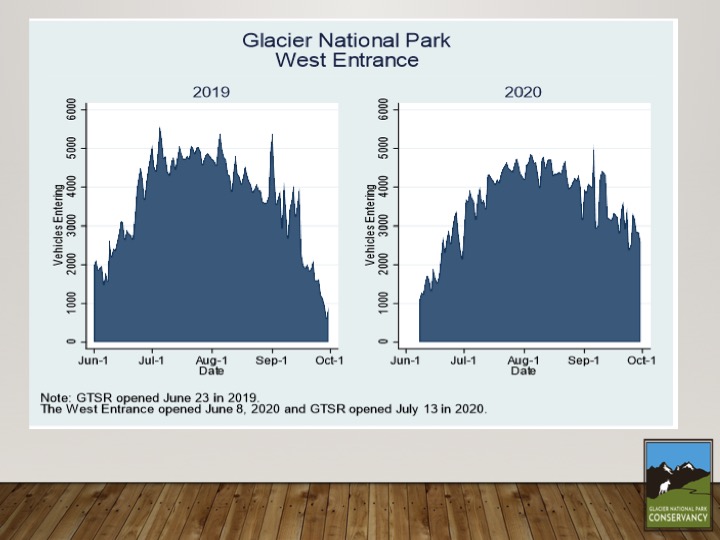

Chart that curve on a PowerPoint slide, as Mow has been doing for the past two months in his presentation, and it bristles with an electrocardiograph of peaks and troughs, with the sharpest peaks in recent years representing periods of intense visitation so high that they forced temporary closures — days when parking lots were so maxed out that park officials swung the gates and turned visitors away at various entrances, sometimes on a daily basis.

Last summer, in the throes of a pandemic, those peaks in visitation triggered closures at Glacier Park’s popular west entrance on 25 occasions, with 18 of the closures occurring in June, before the Going-to-the-Sun Road had even opened to its high point at Logan Pass, atop the Continental Divide. The remaining seven closures occurred in August and around Labor Day weekend, after the Sun Road had opened to Rising Sun Campground, at which point motorists were forced to turn around due to closures on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation.

“If we have visitation on the west side that resembles anything like what we had in 2020, we will be closing the west entrance potentially 25 times at some point this year,” Mow said. “Whether we close for two hours or whether we close for five or six hours, we don’t know. But there will be closures.”

Last year, congestion related to those closures became so badly bottlenecked that it gridlocked traffic well beyond the park’s border, snarling traffic along U.S. Highway 2 for miles. If those circumstances were to repeat themselves this summer, they’ll be exacerbated by a months-long pavement preservation project spanning a 40-mile segment of U.S. Highway 2 from Hungry Horse to Essex, which serves as the park’s key exterior corridor. Road repair work is also scheduled for nearly every other corner of the park, including the popular Many Glacier Valley.

So far this year, the biggest factor working in Glacier National Park’s favor is the Blackfeet Tribe’s decision to allow the park’s eastern entrances to reopen for the 2021 visitor season. Tribal leaders based that decision on a vaccination rate nearing 100% among eligible enrolled Blackfeet members, as well as on the recent adoption of a new set of guidelines for reopening the reservation’s economy.

The unanimous vote came one year after tribal leaders declared a state of emergency due to the COVID-19 pandemic, a grim milestone that members of the Blackfeet community observed on March 15 by paying respects to the 47 tribal members who died as a result of the virus, as well as by celebrating the lives saved due to the aggressive steps that Blackfeet officials took to protect the reservation’s most vulnerable residents.

“Here we are one year later, and we’re here, which is worth celebrating,” BTBC Chairman Tim Davis said during the one-year commemoration. “We recognize all those that we have lost, all of our loved ones. Every one of us has a connection with someone who died. We all want to get back to normal, but the new normal is not going to be normal. It’s going to take time and we need to continue to be vigilant.”

Inside the reservation, that vigilance has been on prominent display through restrictions that have far outweighed those required either by Montana’s statewide mandate or by local decree, and will continue to include masking requirements “for an indefinite period of time,” according to James McNeely, a tribal public information officer.

But the restriction with the highest consequence beyond the reservation’s boundary was the tribal council’s decision to block access to Glacier’s eastern entrances, including at Two Medicine, Chief Mountain, St. Mary, Cut Bank Creek, and Many Glacier. Because Glacier National Park draws millions of visitors each year, with hundreds of thousands of them accessing the park by crossing tribal lands, the potential for tourism to exacerbate the public-health crisis during the pandemic presented an unacceptable risk, tribal leaders said.

Mow and his administrative team immediately endorsed the Blackfeet Nation’s decision to maintain the closures last year, and he has been uncompromising in his stance that a decision to reopen the eastern entrances in 2021 would only be arrived at with the Tribe’s concurrence.

But he didn’t hide his relief last week when the Blackfeet Tribal Business Council passed its resolution to reopen the border, acknowledging that it will go a long way toward easing congestion at the park’s west entrance, by far its busiest.

Still, Glacier Park International Airport Director Rob Ratkowski has predicted the region will see more scheduled inbound flights this summer than it did in 2019, which was the second busiest year on record at Glacier National Park. The anticipation of an influx of summertime visitation, Ratkowski said, is because airlines are adding more seasonal services to the region in order to capitalize on an increased appetite for leisure travel.

Advanced bookings for hotels and rental cars are also “off the charts,” according to Mow, and the park’s free and popular shuttle system will run at below capacity to accommodate social distancing this summer, if it runs at all. Meanwhile, Mow is grappling with a staffing shortage of roughly 70 employees due to COVID-19 mitigation measures requiring every staff member have their own bedroom, which will mean fewer services can open up inside the park, including popular campgrounds at St. Mary and Rising Sun.

“We really do have a confluence of issues coming to bear on our 2021 visitor season. And what we want to do is take the edge off peak demand, particularly at the west entrance, and hopefully eliminate the need to have closures,” Mow said. “But if we have to implement closures, we’d like to do it in a way that’s not surprising to the public. We’d like to do it in a way that doesn’t require us turning people back at the gates. And that’s the concept for ticketed entry.”

The deftness with which Mow introduces the concept of ticketed entry runs in direct correlation with the number of times he’s delivered his presentation, and the public’s reception has been following a similar trajectory, with the most vocal support on March 18, when hundreds of attendees logged into a community discussion hosted by the Glacier Park Conservancy, the park’s nonprofit fundraising partner.

Mow began “socializing” the proposal for a ticketed-entry or reservation system last summer, after the Department of Interior granted park administrators a wide berth of flexibility to introduce new tools to help manage pandemic-related issues, including congestion. In Glacier, where overall visitation was down 40% last year because of the pandemic-related closures, the idea of a ticketed-entry or reservation system never gained traction in gateway communities, in part because the concept wasn’t introduced early enough, and because Glacier isn’t equipped with the geography to turn away visitors lacking the requisite tickets.

This year, Mow started shopping the idea around much earlier, pitching his proposal during the “calm before the storm,” and although he still needs final approval from federal officials at the Interior Department and would like a measure of support from the sprawling community of “business stakeholders” flanking Glacier, he anticipates making a decision one way or another by the end of March or in early April.

As proposed, the pilot program would only apply to motorists along the Going-to-the-Sun Road accessing the park at West Glacier or St. Mary, who would be required to buy a $2 entry ticket through the online recreation.gov portal. The tickets would be required from June 1 through Labor Day, between the hours of 6 a.m. and 5 p.m., and they’d be required in addition to a park pass. Tickets purchased with a seven-day pass are valid for all seven days, but reservations must be validated on the first day the reservation is made. Between 70% and 80% of the tickets would be available to the public 60 days in advance of the reservation date, with the remainder released two days in advance, to accommodate local and drive-in markets that tend to be more spontaneous. Anyone with reservations to hotels, lodges or campgrounds, as well as for boat rides or other scheduled activities within the park, wouldn’t need a ticket. Tribal members and private property inholders also would be exempt from purchasing a ticket, but season pass holders would need to pay the additional $2 to procure a reservation.

The total number of tickets available each day (the quota) would be determined by estimating how many people gain entrance without needing a ticket; how many people are in the corridor for their seven-day visit; and how many people entered after the entrance station closed.

According to Mow, based on the numbers he’s crunched, the “vast majority” of visitors would be able to purchase entrance tickets, while he expects the park would bump up against the reservation quota and have to refuse reservations to some visitors about 26 days during the course of the summer, or one-third of the busiest days.

Glacier National Park also recently finalized its long-awaited Going-to-the-Sun Road corridor management plan to help improve the visitor experience and protect natural resources along the iconic alpine byway. The comprehensive plan has been in the works since 2012, and was crafted with broad input from the public.

Although the final version of the plan stopped short of recommending a ticketed entry system, the park could still implement one this summer as an adaptive management strategy, which would expire after Labor Day.

Michael Jamison, of the National Parks Conservation Association, has been tracking the congestion-related closures at Glacier National Park for years, and said he’s eager to see whether a reservation-style system lends a greater degree of certainty to those visiting the park than the current approach. Moreover, he said he hasn’t heard anyone pitch an alternate solution.

“We clearly have a problem, which has been evident for a few years now, and Jeff has presented a pretty sophisticated and thoughtful solution,” Jamison said. “I trust my park manager to manage my park, so I think we ought to give this a try.”

“Again, what’s the alternative?” he continued. “This is no longer a question of whether or not we are going to restrict entry. The question of whether we are going to restrict entry got answered years ago when we started locking the gates at Many Glacier and Polebridge and West Glacier. There are limits to how many people can access Glacier National Park, so now the question is, do we prepare for those limits? Or do we continue having people show up at the park surprised that they can’t get in?”

Nathan St. Goddard, a Blackfeet tribal member whose family has owned Johnson’s of St. Mary for more than seven decades, said his primary concern with ticketed entry relates to the number of visitors he anticipates arriving at Glacier National Park having no idea that a new system has been implemented.

“I worry they’ll air their grievances on the businesses, and take their frustrations out on us,” said St. Goddard, who last summer was forced to temporarily close his family’s restaurant, RV park and campground. “We have a lot at stake this summer. We need to make up everything that we lost because of the pandemic.”

For Mow’s part, he understands that there’s fear in uncertainty, and has expressed his appreciation for Glacier Park’s business communities again and again during his presentations.

“We view the business community as a vital part of the success of Glacier National Park,” Mow told them. “What you do helps ensure that the millions of visitors who come to Glacier have a good trip, and that is essential.”

“Let’s face it, no matter how good we are about getting the information out, we are going to have people who show up not having those plans or reservations in place,” Mow continued. “But what this will do is provide certainty to the people who do make those plans. The vast majority of visitors will be able to get a reservation and it provides certainty that they’ll be able to visit Glacier Park.”