The old adage branding Montana as one small town with a really long Main Street is an apt one, and fairly captures the corps of compassion that sustains close-knit rural communities, ranging from the Yaak to Ekalaka, where neighbors take care of neighbors. However, the state’s sprawling geography and low population density — characteristics that make Montana uniquely Montanan — has also made it the most federally underrepresented state in the union.

Since 1990, Montana has remained one of only a handful of states that elects a single member to the U.S. House of Representatives, and it currently has the lowest degree of federal representation in Congress: One representative occupies an at-large seat covering all 147,000 square miles, 1 million-plus people and 56 counties, a monumental job with a range of shortcomings, particularly as some segments of the state’s population grow rapidly.

“It’s a really hard job,” Rob Saldin, a University of Montana political science professor, said. “You have to cover the entire state of Montana. It’s two plane rides home from Washington D.C., two plane rides back, and you’re doing it on a shoestring budget compared to what our senators have.”

Denny Rehberg, who served six terms as Montana’s at-large representative in the House, from 2001 to 2013, adopted a signature style of traveling home to Montana from Washington on the weekends and touring vast stretches of the state by minivan, logging 50,000 miles annually as he toured the state holding town hall meetings in all 56 counties every two years — a tact he concedes was more a symbol of his commitment to his constituents than an efficient mode of representation.

“It’s time consuming,” Rehberg said. “It’s the second-largest geographical district in Congress. In an attempt to continue to listen and learn, I traveled to all 56 counties continually. I never lost my enthusiasm for jumping in the car and going to meetings with as many people as I can. But it was tough and time consuming.”

For perspective: Today, Montana’s U.S. Sens. Jon Tester, a Democrat, and Steve Daines, a Republican, each maintain seven district offices across Montana, covering their bases from Billings to Kalispell and at various locales in between.

Meanwhile, U.S. Rep. Matt Rosendale, a Republican, has just three district offices, but covers the same territory.

That’s set to change.

Based on new population data, Montana is slated to gain a second congressional seat, growing from the least represented state in the union to the most represented state, with the national average population per representative sitting at about 760,000. According to U.S. Census Bureau figures released last week, Montana’s population grew by 94,810 residents during the decade spanning 2010 and 2020, a 9.6% spike amounting to an approximate total of 1,084,225 people.

The uptick in growth was good enough to earn Montana the 434th (or, second-to-last) seat available in the U.S. House this redistricting cycle, as elsewhere in the country four states will join Montana in gaining a seat — Colorado, Florida, North Carolina, Oregon, and Texas — while seven states — California, Illinois, Michigan, Ohio, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, and New York — will each lose a seat, barring legal challenges over the precision of population counts.

The news was widely celebrated, even as political pundits immediately began speculating about the state’s forthcoming district divisions.

“No matter how you look at it, this is great news for the state,” Saldin said. “As a lot of people have pointed out it doubles our representation in the House, it adds a whole new set of committee assignments, and splitting the district up will also make it a more manageable geographic territory. But it will also make this a more appealing position for our representatives.”

He continued: “Since Denny Rehberg was in office, we have had a revolving door of one-term representatives who sort of use this as a launching pad to fulfill other political ambitions. So with the addition of a second seat, it will be more appealing for representatives to stick around, develop a policy portfolio, gain those committee assignments, and really start to move in a policy-oriented direction. That is something you just can’t do in a single two-year term.”

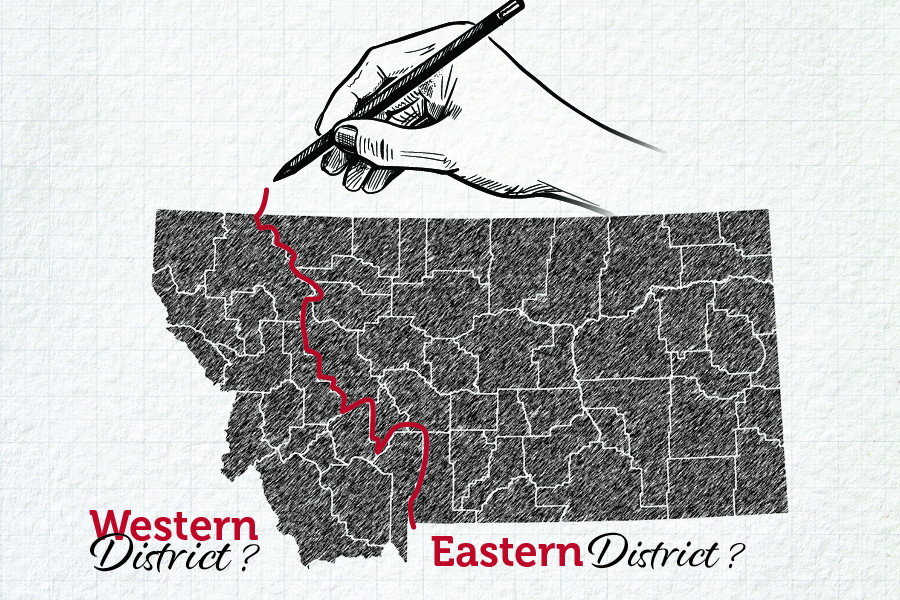

Beginning in 1918, the state had two congressional districts, a western district and an eastern district (from 1912 to 1916 Montana had two at-large districts), but it lost one after the 1990 census, as population growth stagnated during the 1980s.

Determining what the new congressional district looks like on a map is the job of an independent, bipartisan Districting and Apportionment Commission, which is also charged with redrawing legislative districts once a decade. Montana is one of the few states with a redistricting commission, which will apply criteria defined in the state constitution that stipulates a number of standards, including that the state’s congressional districts “shall consist of compact and contiguous territory” and “all districts shall be as nearly equal in population as practicable.”

The districting commission is waiting on a second set of Census Bureau data from its 2020 count, including demographic information and population numbers broken down by smaller geographic units, including counties, towns, and tribal reservations. Once those figures are available by the end of September, the commission has 90 days to accept public comment and deliver a proposal to the Secretary of State. The second seat will appear on the 2022 ballot.

Jeff Essmann, a former Republican state legislator who serves on the redistricting commission as one of two Republican-appointed members, said he intends to offer more specific criteria to help guide the process in order to avoid the influence of partisan biases.

“I think if the process is structured properly, the public will have more faith in the outcome,” Essmann said. “In terms of how to draw the lines we need a clear and comprehensive set of mandatory criteria that are objective, so whether you’re Democrat or Republican or Independent you can hold a map up and say that it followed objective rules.”

“I think the big problem in Montana is the commission has not ever adopted a clear set of mandatory criteria,” Essmann continued. “They only used the brief descriptions in the Montana constitution, which are that the boundaries are compact, contiguous and nearly equal in population. That could all use some definition, and I hope to bring some definitions forward for the commission, and I hope the Democrats will do the same.”

Maylynn Smith, a former University of Montana law professor and tribal attorney for the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, serves as the commission’s nonpartisan chair, and said there isn’t a lot of flexibility to redefine the commission’s constitutionally assigned job.

“The beauty of the Montana Constitution and setting up a redistricting commission is that there’s not a lot of discretion. We were given a pretty clear guide and a clear mandate on how to accomplish this. My job is to fulfill the process,” Smith said. “To an extent it’s all mathematical — there’s only so many ways you can divide Montana in two that’s going to be close in population.”

Joe Lamson, a Democrat-appointed commission member, said that ensuring a precise distribution of the population could mean splitting counties up over the state’s two districts, particularly in more populous areas, where suburban and rural voters don’t intermingle.

“If we have 1 million people, and we’re trying to hit 500,000 on one side and 500,000 on the other side, if it’s much more out of balance than that then somebody is going to have grounds for a lawsuit,” Lamson said. “I think it’s highly likely that some county gets split up along the way.”

Former Montana Rep. Pat Williams, a Democrat who served in the U.S. House from 1979 to 1997 — a period that included the state’s transition from having two House seats to a single at-large seat — said hewing as closely to an east-west divide as possible makes the most sense given Montana’s geographic diversity and “separation of interest.”

In western Montana, for example, liberal-leaning communities like Missoula and Bozeman offer a stark contrast from the eastern plains, which lean conservative. Indeed, the old western district often favored Democrats like Williams, while the eastern district skewed toward Republicans.

But no matter how the districts are drawn, Williams said the second seat would raise Montana’s profile at the federal level, in part by doubling the state’s presence on House committees.

“I served back when we had two seats, and I served when we had one seat, and as I’ve said before, two is twice as nice,” he said.

The at-large district has been held by Republicans consecutively for more than two decades, and the addition of a second district has already energized both parties as they seek to dominate it.

Saldin said the Democrats have reason to be excited about the prospect of adding a tinge of blue to Montana’s sea of crimson, but urged the party not to become overly confident.

“It does seem as though Democrats are overconfident in their chances of taking that western district seat,” Saldin said. “You almost get the sense that the Democrats feel that seat belongs to them. And I don’t think that’s the case at all. I think it will be very competitive, that it will be very far from a guarantee and that if anything it’s more of a toss-up, perhaps with a slight edge to Republicans. But I do think it will be competitive, which should draw some strong candidates from both parties.”

Indeed, within days of the news that Montana would regain a second representative in Congress, a familiar name in politics announced he would run for the newly minted seat — Ryan Zinke.

A Whitefish resident and former state legislator, Zinke served as Montana’s representative in the U.S. House from 2015 to 2017, when former President Donald Trump tapped him to serve as Interior Secretary, a job from which he resigned in 2019 amid ethics investigations. Since then, Zinke said he’s been “recovering” from the toll that Washington politics dealt on him and his family, but his perspective that the country is in the midst of a crisis “driven by division” compelled him to run for office again.

“As Secretary, I rode a horse to work on the first day,” Zinke told the Beacon. “And the point of that was to say that the West deserves a voice and D.C. is heavy-handed. I’ve always said you can’t manage the Yellowstone River if you don’t know where it is, and I have a track record of getting things done in Montana, for Montanans.”

Although a congressional candidate isn’t constitutionally required to live in the congressional district they represent or are seeking election to, Zinke said he anticipates campaigning for a district that includes his home in Flathead County, a Republican enclave in western Montana that was formerly included in the western district.

“I don’t think there’s a need to depart from 100 years of precedent in Montana,” Zinke said. “We should have an eastern district that is compact and contiguous and a mountain district. Any departure from that is going to be perceived for what it is, and an attempt to gerrymander and politicize Montana.”

The use of gerrymandering, or the tactic of using redistricting to draw political boundaries that benefit a particular party, has been criticized by political leaders on both sides in the state, including Gov. Greg Gianforte.

“It’s critical we avoid the traps of partisanship and gerrymandering as our new district lines are drawn. Our new districts should be compact, keep our communities together, and make common sense,” Gianforte said in a statement.

On April 30, the Montana Republican Party announced it was establishing a redistricting committee to prevent gerrymandering and “hold the Montana Districting and Apportionment Commission accountable during the redistricting process.”

“We need to ensure that we have a transparent and equitable process that is free of political calculation or any effort to gerrymander Montana’s Congressional or Legislative Districts, and I look forward to working with community leaders in the months ahead,” according Terry Nelson, a Republican candidate for Montana governor who lives in Ravalli County.

Based on population projections, Montana has been on track to gain a second seat in Congress for years, but pandemic-related stumbling blocks stalled the U.S. Census Bureau’s counting efforts in early 2020. To help volunteers and nonprofit organizations reach every household in Montana’s rural counties, former Gov. Steve Bullock directed $500,000 in federal coronavirus relief funding to boost counting efforts last summer. Still, as commissioners await the more nuanced population data on Montana’s cities and counties, which could be available as early as Aug. 16 or as late as Sept. 30, ensuring that the new district is ballot-ready for the 2022 midterm election is a tall order, Smith said.

For his part, Rosendale, the state’s lone representative in the U.S. House, said he’ll no longer enjoy the novelty of representing a vast state like Montana on his own, he welcomed the announcement as a “great opportunity for the state.”

“Having another member in our delegation makes us that much more powerful and it means we will have representation on more committees that are important to our state,” he said.