The dusty dirt trail heading east out of Holland Lake, over Gordon Pass and down to Big Prairie leads back in time, to the days of tough old forest rangers, plucky packers and a world without ease.

It’s a place where camp cooks once washed the mold off ham shanks to feed work crews when the rations ran low, and cigarette ash mingled with the pepper on scrambled eggs.

There’s no power, no cell tower, no motorized use. Instead of chainsaws, the backcountry rangers who call this burly chunk of wilderness home use crosscut saws, Pulaskis, loppers, and hand saws to perform their work, clearing and maintaining a sprawling network of trails.

In many ways, it’s a way of life that has persisted for more than a century — workers coexisting with wilderness, massaging primitive civilization into the rugged landscape in order to manage the land as wilderness, which, “in contrast with those areas where man and his works dominate the landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain,” according to the 1964 Wilderness Act.

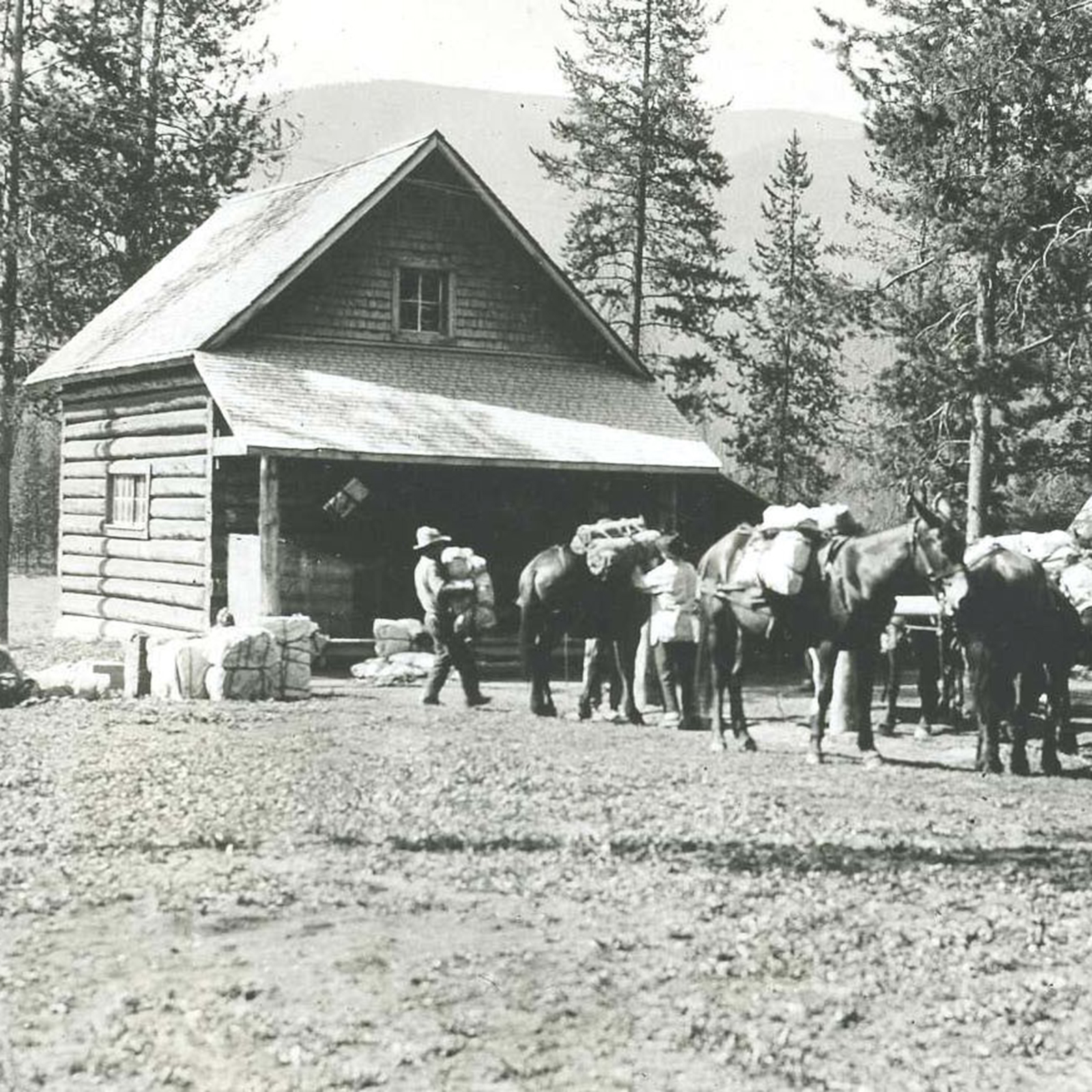

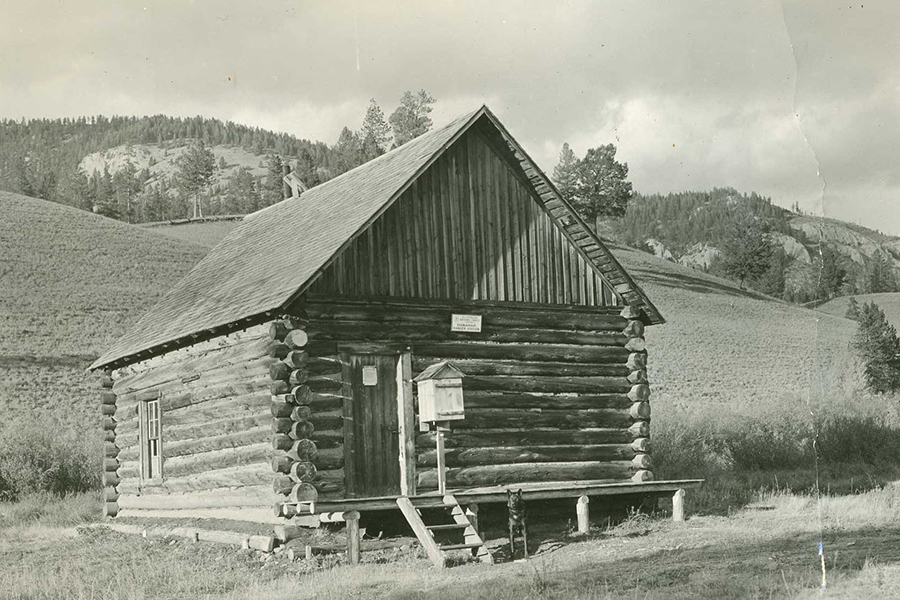

Such is the way of life at the historic Big Prairie Ranger Station, which serves as the center of U.S. Forest Service operations in the upper South Fork Flathead River drainage. Established in 1904, the complex moved to its current location in 1912, while additional buildings were constructed over the decades. Situated on the west bank of the South Fork, Big Prairie continues to serve as a wilderness outpost for forest employees, outfitters and other backcountry travelers.

It’s one of dozens of cabins scattered across the Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex, a swath of about 1.5 million acres spanning Montana’s Northern Rockies. It encompasses four national forests — Lolo, Lewis and Clark, Helena, and Flathead — the latter of which has listed its network of 18 cabins and ranger stations on the National Register of Historic Places just in time for the 50th anniversary of the 1964 Wilderness Act.

Long before their wilderness designation, however, the Forest Service set these lands apart as “primitive areas,” specifically the South Fork and Pentagon primitive areas, established in 1931 and 1933, respectively.

“The current undeveloped character of these areas is owed in large part to the early recognition that they possessed the essential qualities of ‘wilderness,’ as would be codified in the Wilderness Act of 1964,” retired Flathead National Forest archaeologist Timothy Light said.

A 1936 Northern Region pamphlet on the primitive areas states: “There are those areas which only a minimum of civilization has reached, where only the trails and habitations are those required in providing adequate protection from forest fires, and a means of travel for visitors on foot or horseback. These are the ‘primitive areas,’ on which further encroachment by advancing a civilization has been prohibited. They are to remain forever in their present state, with their primitive conditions of environment, transportation, habitation and subsistence, visited only by the more intrepid of present and future populations.”

The creation of the Bob Marshall Wilderness in 1940 went a long way to preserve the administrative buildings — and way of life — of the Flathead National Forest of the 1930s era.

The historic Big Prairie Ranger Station complex is an evocative, living reminder of a way of life that has vanished on most other national forests. Supplies are still brought in by pack strings, about 40 miles of the old telephone system is still in use and workers still wield crosscut saws and other non-motorized tools within the Wilderness. The major change is the almost complete dismantling of the extensive fire lookout network that once played an important role. The Spotted Bear Ranger Station, also in the South Fork but accessible by road, has several well-maintained historic buildings at its complex, plus a number of artifacts relating to the forest’s history on display for visitors.

The national forests and wilderness of Northwest Montana teem with natural wonder and cultural history, including the grand old ranger stations and work centers that for more than a century served as the nerve centers of Forest Service operations, just as packers and their stock provided the lifeblood of an agency whose employees worked and lived deep in a remote and inaccessible territory.

As Flathead National Forest employee John Frohlicher commented in 1930, “If a lookout, ranger, or firefighter is without tobacco, coffee, or even his mail, he is a discontented human being. The mule packs in whatever is necessary for his peace of mind and body.”

Set aside by Congress in 1964 to be forever roadless, the Bob Marshall Wilderness Area features 1,856 miles of trail, but at its height in 1955 the trail mileage totaled 3,150 miles, most of them inscribed in the landscape by Forest Service employees.

Early rangers traveled the landscape by foot and supplied their own riding stock. To ease their duties, the Forest Service developed a network of trails connecting a series of existing cabins placed one day’s ride apart.

Some forest rangers met their future spouses as a result of their duties in the woods, such as Ray Trueman, a ranger at Big Prairie who married Ruby Kirchbalm, a woman who operated a 30-horse pack string between Coram and Big Prairie after World War I.

The old log buildings, many bearing the visible signatures of visitors dating back to the 1940s, can be found in nearly every corner of the wilderness, from the Danaher Cabin built in 1910 on the Flathead National Forest to the Hahn Cabin built in 1923.

Between the mid-1940s and the end of the 1950s, visitation to the Bob Marshall Wilderness increased from roughly 500 to 5,000 visitors — most of whom accessed the area on horseback. Still, management of the backcountry remained relatively unchanged. In the early 1960s, the forest continued to use three of its backcountry airstrips. Its three district headquarters complexes (Spotted Bear, Big Prairie and Schafer) were manned on a seasonal basis, and the guard stations continued to supply shelter to government packers, trail crews and other employees working on research and administrative tasks.

The passage of the federal Wilderness Act dramatically altered some aspects of the Flathead National Forest’s management of the portion of its backcountry system in the Bob Marshall Wilderness. Provisions of the act required the closure of all airstrips in wilderness areas with the result that administrative sites in the Bob Marshall Wilderness would have to be resupplied by pack train. In 1978, when the Middle Fork area was included in the Great Bear Wilderness, the airstrip at Schafer Ranger Station was specifically exempted from the rules prohibiting airstrips in wilderness.

On the Flathead, roughly 45 miles of ground return phone line remains in use, according to Light. The last of its kind, it connects the Black Cabin with the Salmon Forks, Big Prairie, Basin and Danaher cabins.

“In the early years, the cabins were built to help the Forest Service manage the backcountry,” Light said. “After the 1910 burn, we started focusing on fire suppression and the cabins became more important.”

The buildings at Big Prairie are squarely in the middle of the wilderness, while Danaher is difficult to reach and Gooseberry, in the Middle Fork, is even further removed.

The historic structures enliven the backcountry with their history, including tales of unexplained phenomena.

For members of the trail crew at Big Prairie, it’s the sound of footsteps upstairs in the tool shed, which was once used to house the complex’s winter caretakers, back when the Forest Service attempted to maintain a herd of stock in the backcountry through the winter.

During the winter of 1923-24, Clayton Roush, his wife and the couple’s 2-year-old daughter lived at Big Prairie, looking after the forest’s livestock. In January, his daughter became ill, and Roush traveled the 100 miles to Missoula on snowshoes — roughly a weeklong trip — to seek medical advice. Upon his return, he found that his daughter had died a few days after his departure, a period during which his wife was fraught with anxiety and occupied her time worrying about her daughter and pacing back and forth in the upstairs bedroom.

Roush and his wife buried the girl on a small knoll adjacent to the west bank of the South Fork Flathead River, overlooking the building complex.

“Every now and then, when a trail crew is in there sharpening axes and doing things downstairs, they’ll swear they hear footsteps up above them,” Tad Wehunt, wilderness manager for the Spotted Bear Ranger District, said.