A Collection Like No Other

The late Ed Gilliland’s extraordinary historical photo collection will now be preserved forever at Northwest Montana History Museum and available to view online

By Myers Reece

Arne Boveng remembers the hoopla surrounding the sheer size of a 2012 donation to Northwest Montana History Museum that included 1,309 century-old photos shot by Flathead Valley homesteader Matt Eccles.

The collection that today occupies Boveng’s time and fascination, however, is so vast in scope and diversity that it not only “dwarfs” the Eccles archive, but will likely double the museum’s entire existing photo compendium while illuminating corners of the valley’s history rarely, or never, seen by the broader public.

“This is the largest photography acquisition transfer that I know of in the history of the Flathead Valley,” Boveng, a board member of Northwest Montana History Museum (NMHM), said last week.

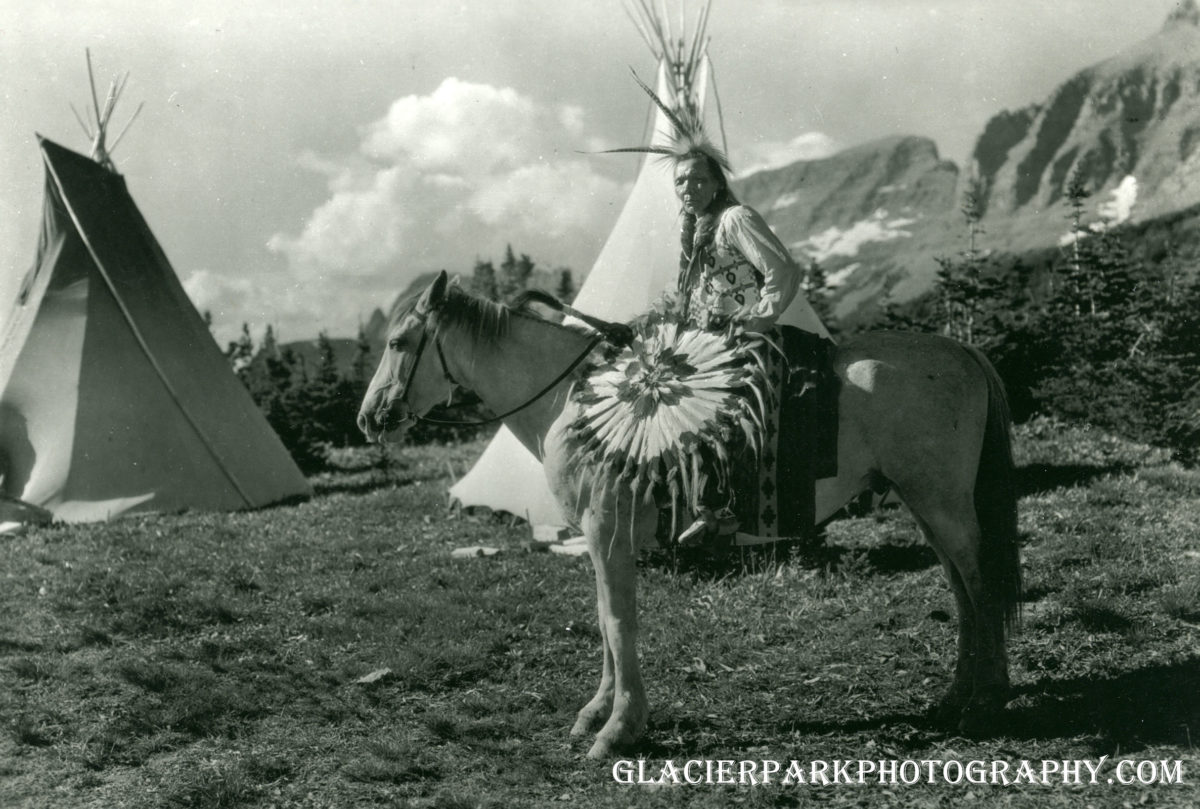

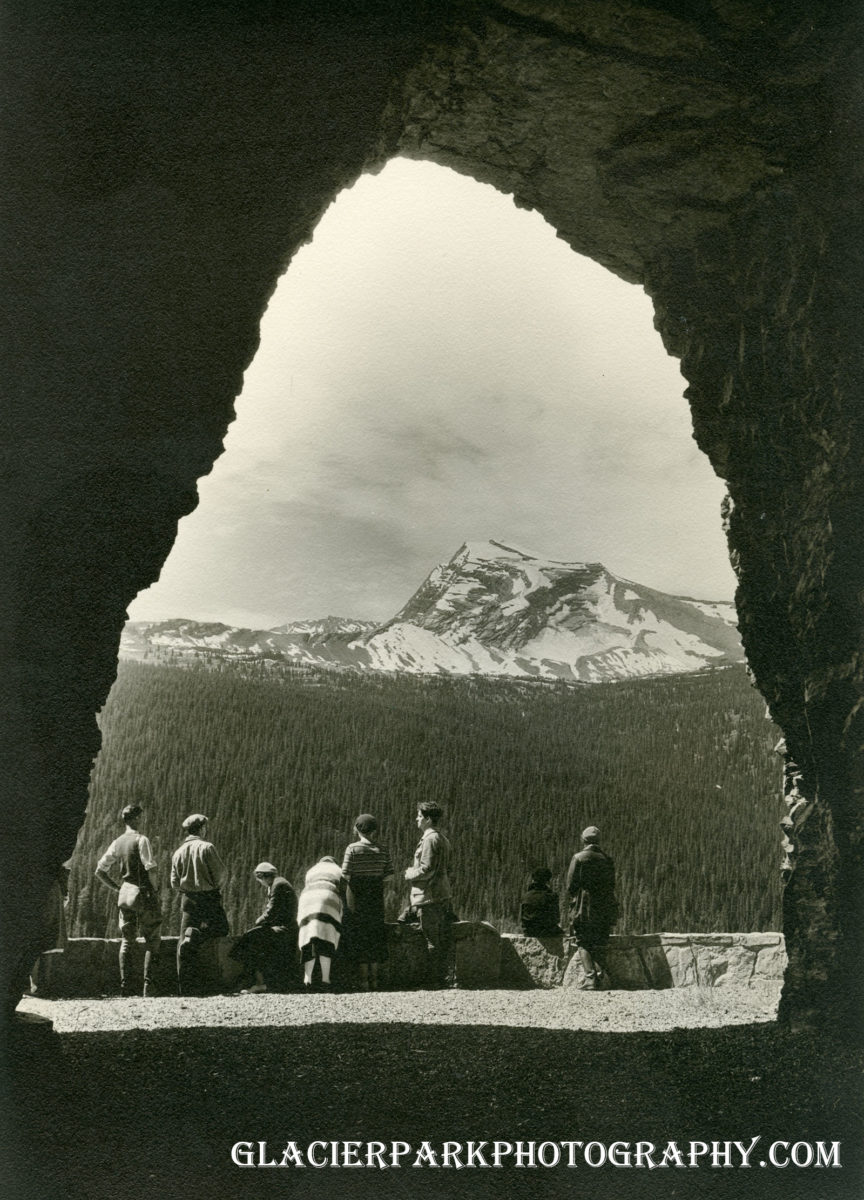

The unrivaled treasure trove was the passion project of the late Ed Gilliland, a Renaissance man and photographer known for both his commitment to shooting large-format color landscapes of Glacier National Park and his tireless efforts to compile and preserve local historical photography.

After Gilliland passed away last September, his wife Nancy entered into a partnership with the museum and Adele Scholl of Gravity Shots to preserve and showcase the extraordinary collection, which had resided in the Gillilands’ Somers home. It includes a massive assortment of prints and negatives, including glass-plate negatives, a technique used before the invention of cellulose nitrate film in the early 1900s.

Under the agreement, NMHM takes possession of the physical collection, while Scholl, who had already been working with Gilliland for years to scan and digitize the photos, operates a website dedicated to the collection called Glacier Park Photography, found at www.glacierparkphotography.com. Proceeds from prints sold on the site are split three ways between Scholl, the museum and the Gilliland family, with the funds used to help with preservation and operational costs.

Boveng said the museum will preserve the collection in perpetuity, according to antiquities laws as well as Gilliland’s wishes, in a stable environment in the NMHM basement. Nancy Gilliland, whose family donation made the transfer possible, declined to be interviewed but said through the museum that she is “super happy with the outcome.”

Much of the collection has been hiding in plain sight on the Glacier Park Photography website for years, un-marketed to the masses and thus un-exposed to everybody except those in the know and anybody who happened to stumble upon it. Thomas and Boveng hope the museum can use its resources to bring more attention to the site.

“Some (museum) board members are stumbling on this for the first time and they’re just stunned,” Boveng said. “Hopefully this is the kind of boost it needs to get going.”

“The website is an ongoing part-time process and needs some work,” he added. “We’re going to make it easier to (use).”

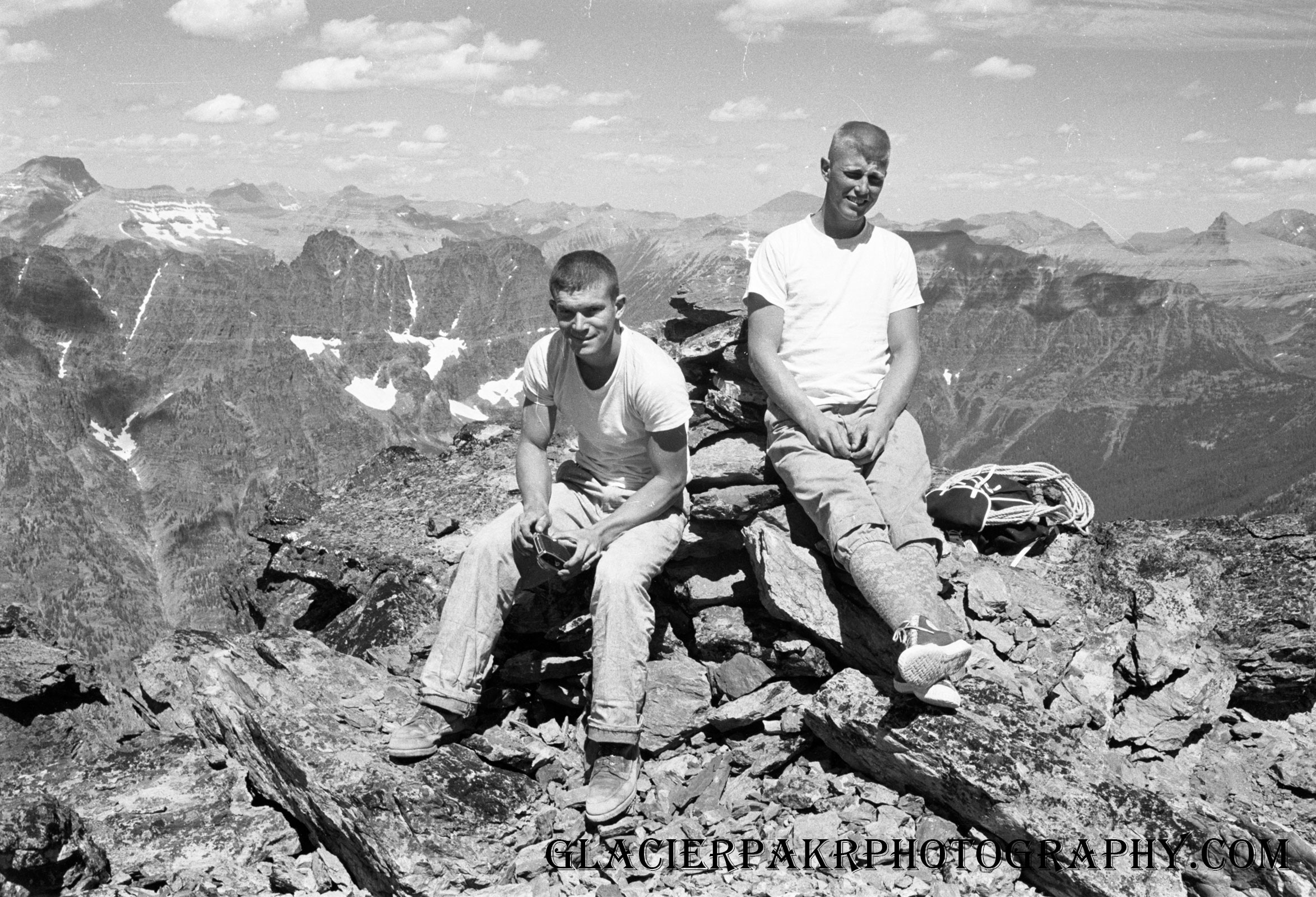

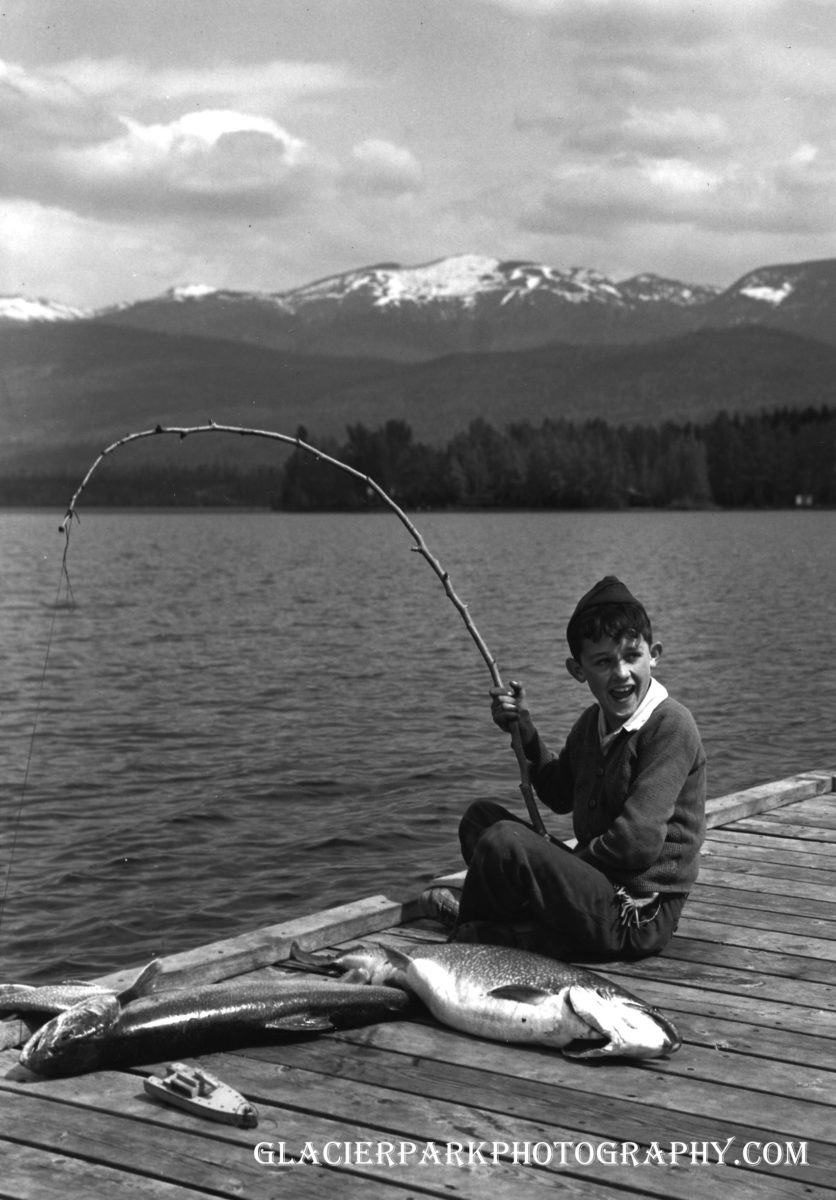

The photos represent a huge swath of time and subject material, ranging from Demersville in the 1890s to the earliest days of each major town in the valley to Whitefish parades in the 1960s and Plum Creek mills in the 1970s. They hail from unheard of or unknown photographers, as well as some of the bigger names in the valley’s history of photography, such as T.J. Hileman, Marion Lacy and R.E. Marble.

Boveng said the archive includes lost collections that Gilliland had found in auctions of early Glacier National Park and the Bureau of Reclamation’s official documentation of Hungry Horse Dam’s construction.

The collection also includes Gilliland’s photography, which NMHM Executive Director Jacob Thomas said carries its own significance. The Gillilands were instrumental in founding the downtown Kalispell museum, formerly called The Museum at Central School, in the 1990s.

“I like this collection not only because of the quality and what it contains and saving the history of Marble and Lacy and all the old photographers, but also to honor Ed and preserve Ed’s work,” Thomas said. “It goes full circle for a guy who helped start the museum and now his life’s work is going to be preserved here at the museum.”

Boveng, a longtime researcher of local history who is particularly knowledgeable in historical photography, played a lead role in brokering the acquisition and transfer between the parties. Boveng formed a relationship with Gilliland over the years, in part through the museum but also through family connections and a shared interest in history.

The Gillilands were friends with Boveng’s parents, and both couples were part of the tight-knit cadre of early Big Mountain ski pioneers, mingling with the likes of the Schencks and Muldowns. Upon meeting him, Boveng said Gilliland dug up photos of his father Oystein Boveng, who was inducted into the local ski hall of fame.

“Ed rummaged through stuff and found Big Mountain photos of my dad that I had never even seen,” Boveng recalled.

Gilliland exhibited some of the collection at his 344 Gallery in downtown Kalispell and showed images to fellow members of the Glacier Camera Club, but the full scope wasn’t obvious to the public and is still coming into focus as Boveng and Scholl continue sifting through the immense compilation.

Boveng notes that, in addition to Gilliland’s relentless search for historical material, people would just show up at his doorstep with family heirlooms and artifacts because they knew of his reputation as a “collector and preserver.” Coming across these surprise gems, Boveng realized the untapped historical potential.

“A lot of it he had never even opened as the years went on in his older age,” Boveng said. “We’re going to be digging up some cool history in there.”

Roughly 4,000 photos have been digitized for the website so far, and Scholl believes there could be 6,000 to 8,000 more to go. For one, Scholl hasn’t scanned any of the antique glass-plate negatives.

“I’m scared to even touch them,” she said.

Plus, Boveng said there are images that have historical value but lack the quality to join the online showcase, as well as other non-photo items. Scholl currently has much of the physical collection at her office, but it will all ultimately be transferred to a dedicated space at the museum.

Scholl said Gilliland “loved history and wanted to share it with everybody,” which was the impetus for the website. Over the years, she has volunteered countless hours digitizing the collection. With a full-time job, she notes that the process is necessarily gradual: dusting and preparing the images for scanning, and then meticulously bringing them to life in a way that would make Gilliland proud.

“I’ve toyed around with getting an intern, but I’m just too particular, as Ed was,” Scholl, who befriended Gilliland through the Glacier Camera Club, said.

“I would talk to Ed about what he would want to happen when he passed away,” she added, “and one of his concerns was, ‘Who could handle the collection, and who has the money to maintain it and make sure it’s safe?’”

The collection includes some photos that a number of people will recognize, including Lacy’s early Big Mountain images, but it also features a plethora of images likely unseen by more than a few eyeballs for decades, perhaps ever.

“A lot of those photos were forgotten about,” Boveng said. “I’m sure the photographers at the time did their best to get the photos seen. Maybe some of them were in the newspaper at the time. Then decades go by and nobody has seen them.”

One notable example is the set of images taken by Ferde Greene during the World War I through World War II eras that document early Columbia Falls in detail. Gilliland purchased the Greene collection from the photographer’s son after it had been stored away since the 1940s, according to Boveng.

Greene’s photos are accompanied by his meticulous field notes, which serve as valuable historical texts, detailing the exact time of day the photos were taken, shutter speed, f-stop and other details.

Glacier Park Photography also showcases a number of images from the separate Eccles collection, for which Gilliland played a critical role in bringing to the museum. A family had dropped the Eccles glass-plate negatives off at Gilliland’s house, and he “funded the pricey cost of having all those glass plates scanned in high resolution” at Photo Video Plus, Boveng said.

Gilliland tirelessly scoured auctions and eBay with purposeful intent and a trained eye, rather than simply a hunger to accumulate. Boveng said he sought unique and historically significant photos, and knew when a collection was special. He operated a first-rate photo studio in the basement of one of the downtown Kalispell buildings he owned, where he made black-and-white prints from negatives. To develop other prints, he used selected out-of-state studios that met his high standards.

Gilliland was a third-generation Montanan born on Sept. 21, 1939 in Whitefish. According to his obituary, his primary occupation was working for Burlington Northern Railroad until a crippling accident on the job forced him into retirement in 1988. He also owned and operated numerous business and real estate ventures around the valley, and had a lifelong passion for photography and sailing. He passed away on Sept. 17 last year.

In addition to the Northwest Montana History Museum, Gilliland was involved with the Hockaday Museum of Art, Somers Company Town Project Museum and North Flathead Yacht Club.

Boveng will present an “analog film night” showcasing Gilliland’s large-format photography on Aug. 18 from 6 to 8 p.m. at Northwest Montana History Museum. The presentation will feature negatives from photos Gilliland took in the 1980s and 1990s, and which Boveng said are a rare treat for keen-eyed photography aficionados.

Thomas said the museum will display selected items from Gilliland’s archive, but for the most part the physical collection won’t be handled after it’s stored and catalogued in order to preserve it. Most of the images, however, will be available as digital files, including on the Glacier Park Photography website.

“The more times these prints and negatives are handled, the less stable they become for the future,” Thomas said.

Thomas is thrilled that the collection will “live at the museum forever.”

“It’s a collection that I don’t know if it has an equal as far as the importance of photography of the history of Northwest Montana,” he said.

For more information, call the museum at (406) 756-8381, or visit www.nwmthistory.org or www.glacierparkphotography.com.