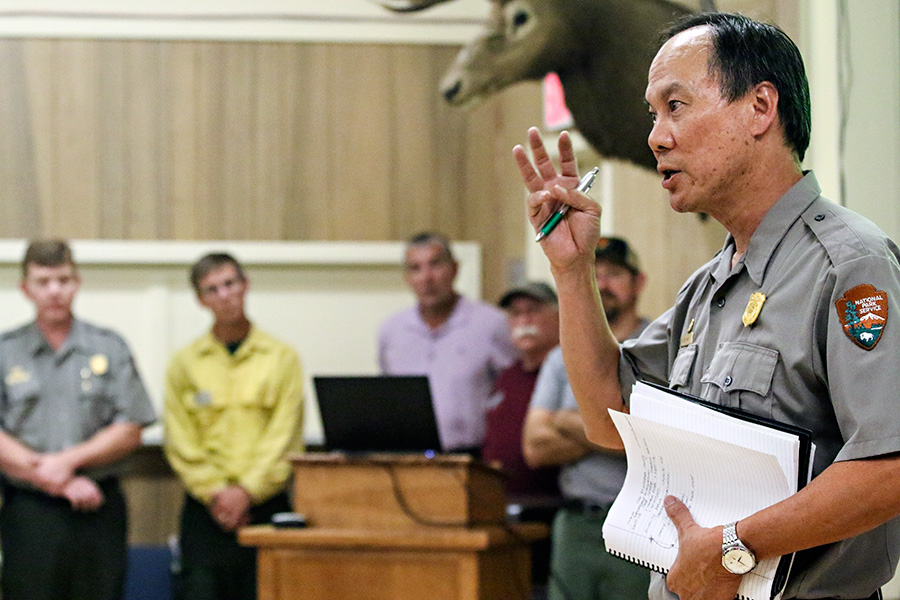

Glacier Park Superintendent Jeff Mow to Retire

After spending eight years as the chief of one of America's most iconic national parks, Mow will step down at the end of this year

By Tristan Scott

Having shepherded the ‘crown jewel’ of the National Park Service through destructive wildfires, an ongoing climate crisis, government shutdowns, the crush of record-breaking visitation, and a once-in-a-century pandemic, Glacier National Park Superintendent Jeff Mow is set to retire after an eight-year tenure during which he negotiated challenges of dizzying complexity.

No matter the scope of those challenges, which included rebuilding an historic alpine chalet in the aftermath of a destructive wildfire and working alongside Blackfeet leaders to buffer vulnerable tribal members from the threats of the pandemic, Mow’s colleagues and partners say he confronted them with aplomb.

“I would say he had the most complicated tenure of any superintendent at Glacier, and he did it with a lot of respect, kindness and grace,” Michael Jamison, of the National Parks Conservation Association, said. “It took a certain kind of person, honestly, especially at a park that is so intimately tied to its local communities and tribes. Jeff took that really seriously, and it’s reflected by the depth of the relationships he developed.”

Mow’s announcement comes on the heels of a summer that marked uncharted territory for Glacier, which for the first time in its 111-year history adopted a ticketed-entry system for motorists on the iconic Going-to-the-Sun Road in an effort to relieve congestion. It was a summer that Mow observed from afar, however.

In April, Mow assumed a temporary position overseeing the National Park Service’s Alaska region, an administrative shake-up that threatened to upend Glacier’s newly minted system before it had even begun.

Although the brand new system predictably faltered at times, Glacier’s 1-million-acre wilderness survived the summer unscathed, and its pilot program, despite some missteps and unintended consequences, worked as planned. It now stands out as a valuable management template for other popular parks struggling to negotiate the challenges associated with over-crowding, Mow said.

Mow’s efforts to broker long-standing partnerships with local stakeholders paid steep dividends in his absence, but he also learned something new during his six months overseeing the Alaska region — Glacier National Park is in very capable hands, he told the Beacon, and now is as good a time as any to pass the torch.

“There was something about stepping away for the past six months and just watching that gave me a lot of confidence. I am just so pleased with how the staff carried out our mission,” Mow, who will retire before the New Year, said in an interview. “I think what every superintendent dreams of is having a staff that functions pretty seamlessly in their absence, and I definitely have a dream team.”

Having spent 33 years with the National Park Service, including the last eight years at Glacier, Mow said retirement is something he’s been considering for some time. That consideration gained urgency in light of several personal issues, including a desire to spend more time with his 98-year-old father, as well as wanting the freedom to visit his son, who is moving abroad.

“I just need to spend more time with my family and enjoy this community as a citizen,” Mow, who lives in Whitefish with his wife, Amy, said. “And to be quite honest, the earlier I can put it out there that I am retiring, the more time the park has to prepare for a new superintendent. And hopefully that person is in place this next summer.”

As superintendent of Glacier, Mow oversaw management of 1 million acres of parkland, a staff of roughly 155 and an annual base operating budget of more than $14 million.

Originally from Los Angeles, Mow graduated from Carleton College in Minnesota, where he majored in environmental education. He later attended graduate school at the University of Michigan, focusing on geology. He first joined the park service in 1988 as a seasonal park ranger at Glacier Bay National Park and Reserve in Alaska. Later that year, he made his first trip to Glacier Park when he was sent to Montana for two weeks to help fight the Red Bench wildfire near Polebridge.

A few years later, he got his first fulltime job at Klondike Gold Rush National Historic Park in Skagway. Later, he moved to the Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve, where he served as district ranger, chief of operations and subsistence manger.

In 2002, he became superintendent of Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument in Colorado. Two years later, he returned to Alaska to become superintendent of Kenai Fjords, a position he held until 2013.

In 2012, he served as acting superintendent of Denali National Park for four months, making Glacier his fourth assignment heading up a national park.

Although managing a national park was nothing new to Mow when he arrived in Montana, he said there were some stark differences between overseeing a rural park in Alaska and one of the nation’s most popular preserves that sees nearly 2 million visitors annually.

“In Alaska, we considered 400,000 or 500,000 people to be huge visitation numbers, well that pales in comparison to Glacier,” he said.

Upon arriving in Glacier, Mow listed climate change as one of the most significant issues facing the park. To help shape his management vision, he drew on his experience developing climate scenarios in Alaska, as well as his work as an investigator on the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill and as the Interior Department’s Incident Commander on the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill in the Gulf of Mexico.

“I would rather not think of it as a career rooted in disasters, but very early on in my time with the park service I found myself encountering them pretty regularly,” Mow said. “I learned a lot about being a leader on climate-related issues in Alaska, and I also learned a lot about living in small, rural communities and working with Alaska Native populations. All of that has been integral to my management role here at Glacier.”

Although last summer’s ticketed entry system on the Sun Road saw its share of critics, Mow said he believes the lessons learned will help serve Glacier and its stakeholder communities for years to come. He also takes comfort knowing that he deepened the park’s relationship with the Blackfeet Nation, working with tribal leaders on a number of initiatives, including a nascent program to return bison to their native landscape on the Rocky Mountain Front. The strength and resolve of those relationships were tested when, in March 2020, tribal leaders declared a state of emergency due to the COVID-19 pandemic, voting to block access to Glacier’s eastern entrances that draw millions of visitors each summer. The potential for tourism to exacerbate the public-health crisis was the main driver for the decision, and the tribe found a sympathetic leader in Mow, who endorsed the decision at every turn.

“The Blackfeet Tribe takes this opportunity to thank Glacier National Park Superintendent Jeff Mow for his years of service to the park and for the wonderful working relationship he established with the Blackfeet Tribe,” James McNeely, a tribal spokesperson, said. “Together, both entites worked in the best interest of all. We wish him the best of luck in his retirement and want him to always know he’s welcome to visit us at anytime.”

In 2017, immediately after the Sprague Fire reduced the 106-year-old Sperry Chalet in Glacier’s high country to a smoldering ruin, Mow set to work brokering the partnerships necessary to rebuild the historic structure.

“Rebuilding Sperry Chalet is definitely a once-in-a-lifetime experience, and the partner engagement was remarkable,” Mow said.

One of those partners was Doug Mitchell, executive director at the Glacier National Park Conservancy, the park’s nonprofit fundraising partner, who recalls asking for Mow’s blessing before taking a credit card to the hardware store in Columbia Falls and buying its entire timber inventory to brace the chalet’s stone masonry, ensuring its survival through winter.

“I’m so honored to have had the opportunity to work with and learn from Superintendent Mow,” Mitchell said. “His commitment to the park, its history, and its future represents what’s best about public service. Every day Jeff worked to develop meaningful relationships and impactful partnerships. His focus was always on how our shared work today could impact the park for the next hundred years, and the impact of his visionary leadership will last for generations. I am a better person for his friendship, and we are a stronger Glacier community because of his service here as Superintendent.”

Mow hopes the relationshops he built endure with the next phase of leadership at Glacier, though he doubts the challenges will diminish in their complexity.

“If there is a hallmark of my time at Glacier, I hope that it’s to instill a sort of thinking about what is possible when you have strong relationships and partnerships with the local communities, agencies and tribes,” Mow said. “Because whatever I may have accomplished wouldn’t have been possible without them.”