A Miracle on Ice

Moments after a 26-year-old hockey novice’s proudest sporting moment materialized with a game-defining goal in Whitefish’s adult hockey league, he was on his knees saving the life of a 67-year-old local legend

By Tristan Scott

Last month, when Tyler Weathersbee wobbled onto the ice to join his teammates for an evening of “E” league adult hockey in Whitefish, his prospects of scripting one the greatest moments in sports history were relatively low.

A paramedic by training, Weathersbee’s only bonafides on the rink were, until recently, those of an avid NHL fan with a nagging college football injury. That started to change when he joined the Whitefish Adult Hockey Association (WAHA) in the fall of 2020, at the age of 25, simultaneously learning to skate and play the game from scratch. It was a daunting undertaking for the former college tight end from Sacramento, California, even as the league’s spirit of inclusion and the tutelage of its seasoned veterans combined to create an easygoing atmosphere well-suited for newcomers like Weathersbee.

One veteran who left an immediate and lasting impression on the younger, less-experienced player is Jack Fallon, 67, who helped introduce Weathersbee to the ins-and-outs of league play, explaining the game’s various positions and its complex rules, and assuring the rookie that, despite his adult-onset introduction to the sport, he was not alone in being wholly consumed by an irrational enthusiasm for hockey.

“When I decided to start playing hockey at the age of 25, I had never even been on snow let alone ice,” Weathersbee, who is now 26, said recently. “Growing up in California, I just didn’t have the opportunity. But I love the uncomfortable feeling of trying something so new that the only thing for certain is knowing I’m not better than anybody. It’s humbling and exciting. When I joined the rookie league, they put on these skill sessions and skating clinics, and Jack helped make it a lot less intimidating. He was kind of a legend.”

After his inaugural season playing with WAHA, Weathersbee took a break over the summer to rehab a trick knee, but he fought his way back to health and was drafted in October as a center on the Cedar Creek co-ed team, playing opposite of Fallon.

Having mentored dozens of less-experienced players in the past decade-and-a-half, Fallon’s recollection of his introduction to Weathersbee is a little different, although he does remember their first time crossing paths.

“He’s a big kid, so when he runs into you, you know something’s run into you,” Fallon said. “Early on, when you’re learning to skate, you end up using other players to help you stop, or you use the boards. So there were a few conk-like encounters where he might have bumped into me or jarred me a little. It’s just part of the game.”

Growing up in St. Louis, Missouri and Detroit, Michigan, Fallon played both soccer and hockey in his formative years. As an adult, however, he trained his attention on soccer, refereeing and playing in various intramural leagues for the better part of four decades. He moved to the Flathead Valley in 1983 and even helped with the formation of several youth leagues. In 2005, a fellow soccer referee encouraged Fallon to volunteer as a hockey linesman, and soon he was refereeing both sports while continuing to play soccer. In 2014, however, a hip replacement forced Fallon to seek out a lower-impact activity, so he traded in his referee’s armbands for a hockey jersey and pads.

“In soccer, there’s a lot of pounding on the hip joints and that made it an easy transition to hockey,” Fallon said. “Yes, you run into people in hockey, and, yes, you fall down. But you’re wearing pads and you’re quite protected. The orthopedic surgeon who did my hips plays in adult league hockey and he encourages my playing.”

Despite the depth of Fallon’s experience on the ice, aging has slowed him down, even if it hasn’t tempered his enthusiasm. His left hip replacement in 2014 was followed by a heart attack in 2015, requiring a stent, and in April 2018 he underwent surgery for a second hip replacement, this time on his right side, which forced him to skip WAHA’s spring and summer seasons.

Although he’s primarily played in “C” league (WAHA’s co-rec categories run “A” through “F”), Fallon dropped down to “E” league in the fall of 2020, which is how on Nov. 14, 2021, he came face-to-face with Weathersbee.

Both men were playing the center position for opposite teams, with Fallon on the “Firebranders” and Weathersbee on “Cedar Creek.” In the third period, Cedar Creek had notched a 3-2 lead when Fallon took a shot on net and missed.

“I was on the ice skating back toward my end when, in the neutral zone near the halfway line, I fainted and fell to the ice,” Fallon recalls.

Meanwhile, play continued as Weathersbee received a pass from a teammate and buried the puck bar-down for only his second goal of the season, a score that prompted a raucous team celebration as Weathersbee skated around the net pumping his gloves in the air.

But something was wrong.

“I was celebrating with my team and had just finished turning around the net when I saw Jack was face first on the ice,” Weathersbee said. “I skated up to him and asked if he’d been hit. He was breathing but unconscious, so I yelled for someone to call 911, because people don’t just suddenly lose consciousness for no reason.”

Over the course of the next several minutes, a rapid succession of events unfolded that were at once frantic in their pace and exemplary in their execution. Weathersbee observed Fallon’s breathing slow and degenerate into ragged wheezing, or what paramedics call “sonorous respirations,” before the labored breaths ceased altogether.

“Once he stopped breathing we flipped him over on his back, checked his pulse and immediately started chest compressions,” Weathersbee said. “That’s when I asked for an AED.”

An automated external defibrillator, or AED, is a portable electronic device that diagnoses life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias and, if necessary, helps re-establish a pulse by administering an electrical shock. Fortunately, the Stumptown Ice Den is equipped with a wall-mounted AED kit and WAHA League Commissioner Kevin Durkin launched into action, grabbing the machine and sprinting onto the ice as dozens of other players and bystanders gathered in the stands. The men used a scissors included in the AED kit to cut away Fallon’s jersey and connected the pads to his chest. Weathersbee administered a shock, the force of which lifted Fallon’s torso off the ice, but his breathing didn’t resume.

“He was completely pale and had no pulse so I continued performing CPR,” Weathersbee said. “It felt like five or eight minutes, but as soon as the ambulance arrived he started breathing and he became more flush with color. When EMS loaded him up he was talking and awake and alert. He was alive again.”

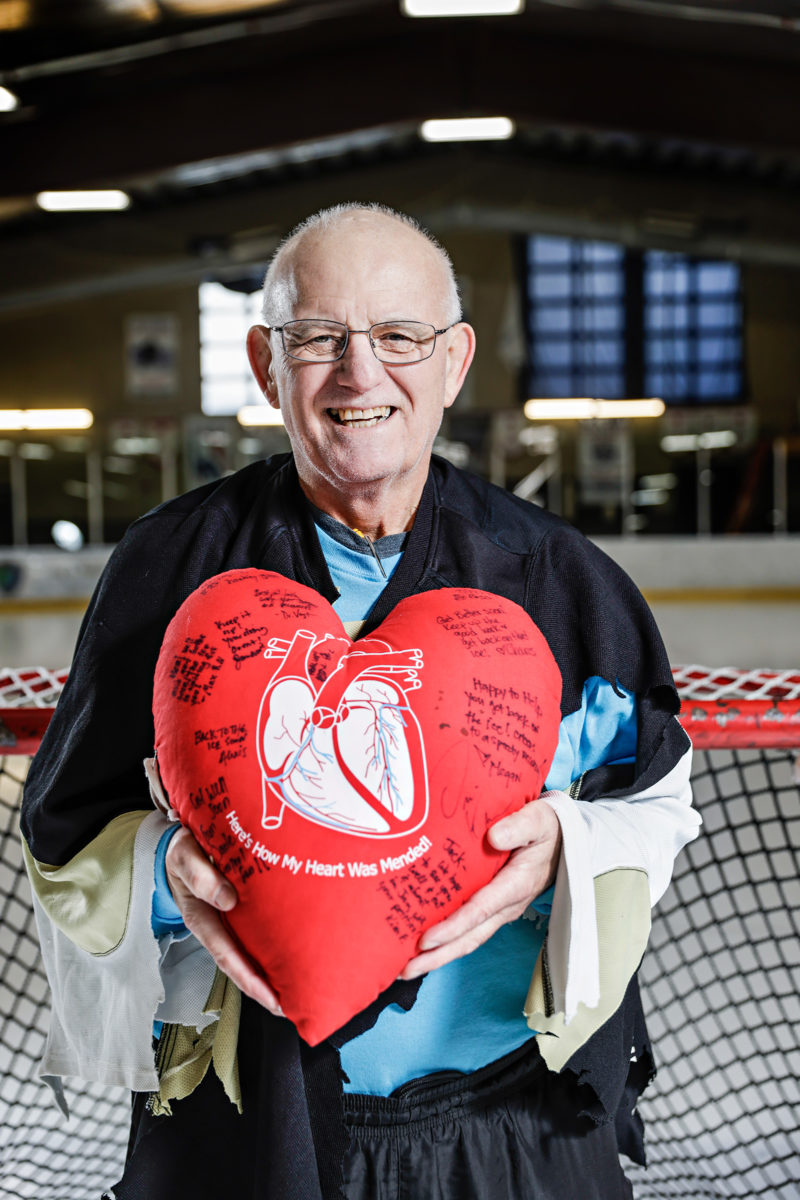

Three days later, Fallon underwent triple-bypass surgery, a successful operation that cleared a 95% blockage above his stent, as well as blockages of between 80% and 85% in five other areas.

“What happened to me, where it happened, and the people involved could not have been better timed or choreographed,” Fallon said. “I guess it’s just not my time. The man upstairs has different plans. But there’s no element of this that serves as a wake-up call. There isn’t anything causing me to take inventory or reconsider my path in life. I may not change anything but to remain on the path I am taking. But I am very fortunate, grateful and thankful for each and every person involved.”

“Doctors say I should be good to go to play hockey in April for spring league,” Fallon added.

Even if the event didn’t carry an epiphany for Fallon, his point about the event seeming to have been carefully orchestrated is sharpened when he describes the 48-hour period leading up to his heart attack, which occurred on a Sunday night.

“I refereed a youth game Friday night, refereed three youth games on Saturday and three on Sunday, and I was supposed to sub in the 9:15 p.m. game after my regular game on Sunday,” Fallon said. “A number of the youth games were at the Kalispell rink, which does not have an AED, and that machine was a total game-changer in terms of my outcome. Without the AED at the Whitefish ice rink, I would not be here. Additionally, what kind of impact would my death have had if it occurred during a youth game? I wouldn’t be talking to you and everybody would have a bunch of bad memories stuck in their head.”

That Fallon had Weathersbee orbiting his ranks didn’t hinder the fortuitous sequence of events, and while the younger hockey player may have only recently learned how to play hockey, he’s been honing his skills as a paramedic his entire adult life.

“Thank God I had the training and the wherewithal to do what I had to do, because it was a shocking turn of events,” Weathersbee said. “To go from skating and scoring a goal to doing what I did, that’s not how I intended my night to go.”

Although Weathersbee has lost track of the number of lives he’s saved during his career as a paramedic (he now works as an MRI technician at Logan Health), he can’t recall ever being so moved by a successful resuscitation.

“When I was doing CPR on Jack, there were probably 40 people watching. Our teammates were helping to stabilize him. People who have known Jack for years were standing by crying and upset, there were people yelling his name. And all of that was going on as I’m just trying to focus and keep my composure. They teach you to be like a duck on water — calm on top, but on the inside your heart is racing a millions miles an hour. I was doing my best to stay calm, but there was a moment when I didn’t know if the outcome was going to be successful. It wasn’t a great outlook.”

After Fallon was taken away by ambulance, Weathersbee skated a few laps around the rink to decompress. Bystanders recall feeling as though they’d just witnessed history in the making, a true miracle on ice.

Henry Roberts, a longtime WAHA devotee who watched the events unfold while he was waiting to play in the next game, hasn’t been able to stop thinking about what he saw out on the ice that night, which he ranks as one of the “great shifts in hockey history,” a single “shift” denoting a player’s consecutive time spent on the ice.

“I did a few Googles on ‘great shifts in hockey history,’” Roberts wrote in a recent email describing what happened. “A lot of random events came up. Zdeno Chara once skated 4:18 and killed two teammates’ penalties in one shift. Mike Keenan once forced a young Alexei Kovalev to stay on for almost 7 minutes trying to make a point, and Alexei even scored a goal during the shift. Others have spent their careers seeking a ‘natural hat trick’ — scoring three goals in a single shift. Still others might think you need a goal and a fight in one shift to enter infamy.”

“But the greatest shift in hockey history might not look like any of those things,” he continued. “Tyler’s shift will live on and should not be forgotten. To go bar down and save a man’s life without leaving the ice should be placed in the pantheon of greatest shifts of all time — possibly one of the greatest moments in sports history.”

For Weathersbee, who visited Fallon in the hospital prior to his triple-bypass surgery and recently reunited with his hockey mentor at Stumptown Ice Den in Whitefish, he’s got lots to accomplish before he considers himself an equal to his hockey hero.

Even so, thanks to the WAHA community, Weathersbee feels a powerful sense of belonging.

“I hope to be just like Jack and his friends when I get to be in my 60s,” Weathersbee said. “I will never stop playing this amazing sport. I’m so appreciative of WAHA being so open and accommodating to new players like myself. Because after a game, when everyone is having a beer and laughing and talking about the plays they made or the shots they missed, I don’t feel like an ‘E’ league rookie. I feel like a hockey player.”