A Wild and Scenic Conundrum

With recreational use on the Flathead River's three forks rising to an all-time high, a new management plan is years overdue for the 219-mile corridor, prompting neighboring landowners to cry foul

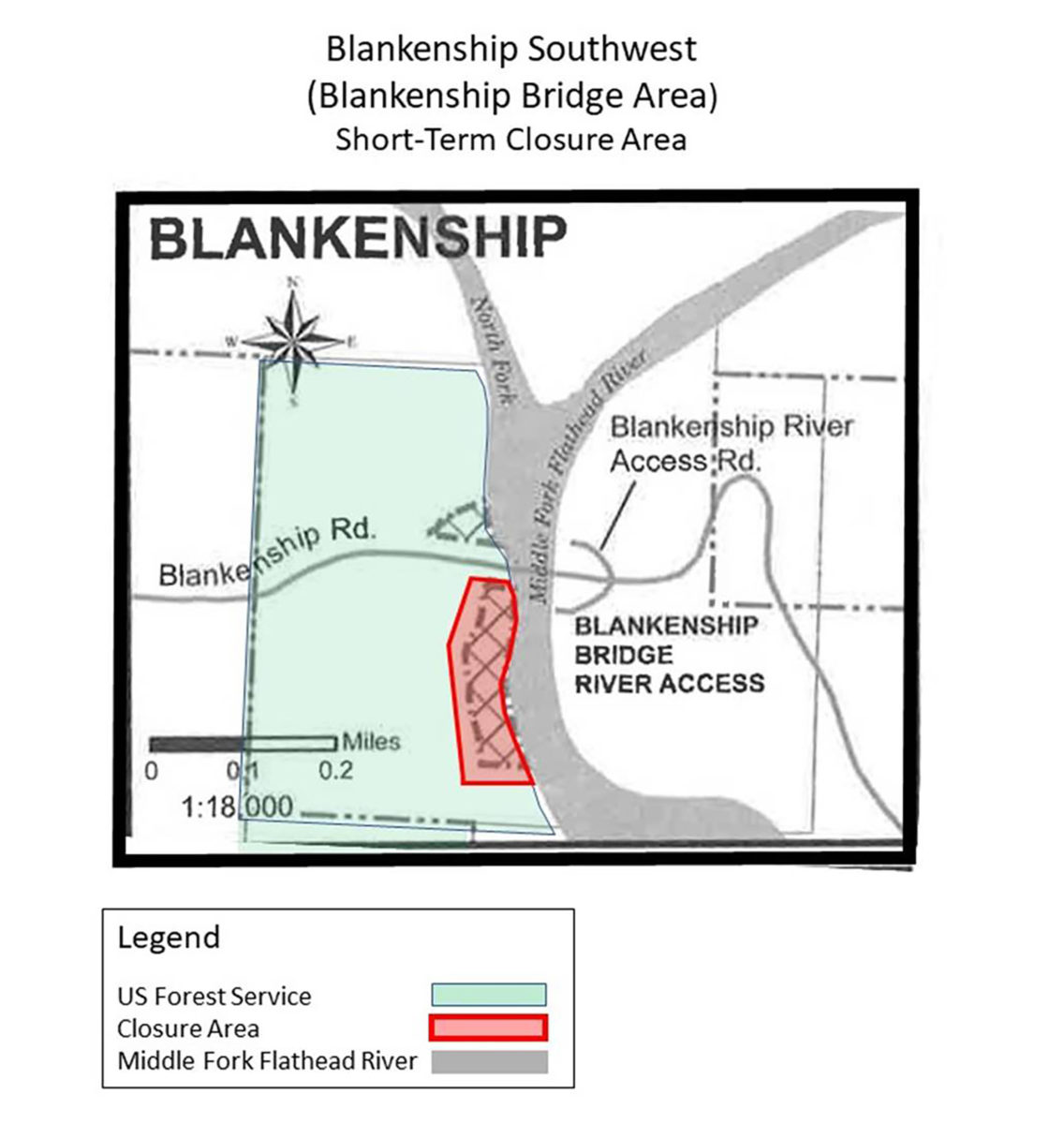

For years, Dan Diamond has tolerated the seasonal boondocking on the gravel bar near his home along the freestone Flathead River, where his family owns a forested parcel abutting federal land southwest of Blankenship Bridge. As the river’s popularity has risen, Diamond has put up with not only campfires and barbecues, mudbogging and fireworks, but also the attendant trash heaps, broken glass, human waste, and other refuse deposited along its banks, chalking them up to nuisance activities — the cost of living near a popular public access site on a world-class recreational river corridor.

Over the last two years, however, Diamond’s tolerance has begun to dry up as dispersed camping along a spit of undesignated Flathead National Forest land has risen to a fever pitch, intensifying from a mere annoyance to an environmental hazard, which Diamond worries could have long-term consequences. It’s a trend land managers say has beset other public access sites in Northwest Montana, too, and which they attribute in large part to the influx of out-of-state Covid migrants commingling with the river corridor’s growing popularity, which has been trending steadily upward for more than a decade, along with just about every other form of outdoor recreation.

“We’ve been watching it get worse and worse, but when Covid came people basically just showed up to live there and work remotely,” Diamond said of the gravel bar. “The numbers were just staggering that first spring and summer and it’s been bad ever since. And unfortunately, these aren’t the paragons of stewardship that understand the outstanding remarkable values of a Wild and Scenic watershed. These people are treating the river like their personal sewer.”

The gravel bar near Blankenship Bridge has been a popular site for locals since it was designated as a dispersed camping location in 2010, but the dimensions of its overnight usage spiked off the charts in early 2020.

“It’s become like Daytona Beach over spring break,” Rob Davies, the Flathead National Forest’s Hungry Horse and Glacier View district ranger, told the Beacon in 2020, when usage picked up in earnest, admitting that the agency was ill-equipped to adequately monitor or manage the surging popularity; instead, land managers opted to install a pair of temporary port-a-potties on the gravel bar.

As the access site took on an increasingly festival-like atmosphere, irked neighbors banded together to air their concerns, drawing up a petition that was signed by more than 200 residents. In it, they demanded the Flathead National Forest prohibit overnight camping at the site and limit it to day-use only. Last summer, however, Flathead National Forest Supervisor Kurt Steele announced the agency would continue to allow dispersed camping at the site, even as local communities braced for record-breaking visitation in the Flathead Valley, due in large part to the popularity of nearby Glacier National Park and the region’s wide array of open spaces.

“Last year the Flathead National Forest was privileged to provide the public a great place for outdoor recreation and we are excited to provide that diversity of opportunity again this year,” Steele explained in a statement following his policy decision. “As a public agency, our job is to provide for a diverse range of recreational opportunity for the American people that want to enjoy their outdoors, including those underrepresented, nature-deprived communities.”

Diamond sees it differently, having recently formed the nonprofit Friends of the Flathead River and formally challenged the Flathead National Forest in federal court, where plaintiffs are seeking to halt overnight use on the gravel bar through a court-ordered injunction. Their hope is to spur the agency to action, restricting camping until there is a newly minted long-term management plan in place.

According to the lawsuit, Diamond and his co-plaintiffs say their tolerance ran out as they observed: campers urinating and defecating directly into the river; campers washing dishes and throwing away food scraps directly into the river; recreational vehicles emptying their “black tanks” and allowing feces and toilet paper to float into the river; and vehicles driving into a spawning tributary used by westslope cutthroat trout, a threatened species.

Indeed, the Flathead National Forest’s proposed action under a long-delayed Comprehensive River Management Plan, released in 2019, recommends the gravel bar be regulated as a day-use site only, but the completion of an environmental assessment and requisite public scoping period for the plan’s finalization has been waylaid.

“For us to go through the planning process to close Blankenship and make it day-use only takes time and requires public engagement,” according to an agency spokesperson, emphasizing that the Flathead National Forest is currently working to address long-term uses on all three forks of the Flathead River through the new comprehensive management plan. “Because we already have this process underway, where we are taking public comment, as long as we don’t have anything that rises to the level of an emergency, the best thing we can do is to continue to engage the public.”

To that end, Diamond and his co-plaintiffs hope to eventually join hands with the federal land management agencies charged with developing and finalizing the plan, including the Flathead National Forest and Glacier National Park. But in order for that hand-holding to occur, Diamond says it’s become clear that a bit of arm-twisting is in order.

Otherwise, it might be too late.

“The motorized vehicle use and excessive camping use on the gravel bar is degrading the quality of the Flathead River. The sheer number of vehicles and people are causing sediment, human and dog feces, and other substances to pollute the Flathead River,” according to Diamond’s sworn affidavit attached to the May 2022 lawsuit, in which he claims to have documented tire tracks in the cutthroat trout spawning creek adjacent to the Flathead River; witnessed campers and recreationalists litter the gravel bar by leaving trash, including broken glass and human waste; witnessed numerous vehicles become stuck in the Flathead River, including a repurposed school bus; and, in April 2022, counted 94 rock fire rings and campfire sites along the gravel bar.

“The excessive use of the gravel bar is ruining the scenic views and the natural landscape of the Flathead River,” Diamond said. “It needs to be regulated.”

Regulatory change has been brewing on the Flathead River’s three forks as officials tasked with managing the Wild and Scenic Rivers System chart a new course on 219 miles of the popular recreation corridors as well as its more primitive stretches.

Designated by Congress in 1976 under the Wild and Scenic River Act, the Three Forks of the Flathead Wild and Scenic River are currently managed under the 1980 Flathead River Management Plan. For the last two years, the Flathead National Forest and Glacier National Park have been updating a Comprehensive River Management Plan (CRMP) for a river system they cooperatively manage, and which considers the significant increase of use (both on shore and by boat) and an obligation to protect the river system’s “Outstanding Remarkable Values” (ORV) as characterized by the federal legislation.

The Flathead National Forest and Glacier National Park currently manage the 219 miles of the Three Forks of the Flathead River under the vintage Flathead Wild and Scenic Comprehensive River Management Plan, as well as the Flathead River Recreation Management Direction, and the current editions of the Glacier National Park General Management Plan and the Flathead National Forest’s Forest Plan.

Work on the lengthy CRMP process got underway in late 2017 and the plan, along with an environmental assessment, was expected to be released for public comment in early 2020, followed by a final decision later that summer; however, staffing and funding issues forced a delay, and the coronavirus pandemic further disrupted progress. The new timeline anticipates a draft CRMP and environmental assessment will be released in the fall of 2022 for public review and comment, including a public engagement session. The final decision and CRMP is expected next year.

To help members of the public brush up on the finer points of a management planning process that only happens every two decades — and in this case has now spanned more than four — a nonprofit stakeholder group called the Flathead Rivers Alliance (FRA) formed with an education-driven mission.

“Management of the Three Forks of the Flathead Wild and Scenic River isn’t simple, it’s complex. But understanding its value and learning what tools are available to prevent degradation does not have to be complex,” Sheena Pate, executive director of FRA, said. “Our goal is to promote a better understanding of those values and create new generations of river stewards so that more restrictive tools like a permitting system won’t be necessary.”

Still, for members of the public to gain a better understanding of how they can help inform the CRMP, Pate says it’s important for them to first learn a bit about the Wild and Scenic River designation under the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System.

The Wild and Scenic Rivers System has three river classifications: wild, scenic and recreational. A single river or river segment may be divided into different classifications, depending on the type and intensity of the development and access present along the river at the time of designation. On the Flathead River system, all three levels of classification exist, and balancing them under the draft plan involves implementing “triggers” and “thresholds” that will prompt management actions, including permitting and limiting the sizes of float groups and restricting outfitters.

Managers use triggers and thresholds to help them set and evaluate levels of resource condition with a prescribed monitoring plan. The Wild and Scenic Rivers Act provides specific direction that a CRMP should describe the existing resource conditions, including a detailed description of the Outstanding Remarkable Values (ORVs) and how to protect and enhance them for future generations.

Before the plan is finalized, the agencies will conduct a final round of scoping and solicit public feedback on the proposed action, including the public’s desired river conditions and preferred markers that would trigger a management decision or action.

“When people hear that we are currently operating on a plan that was created in the 1980s, that resonates with them because they understand that a management plan should be reflective of a landscape and a level of river usage that has changed dramatically,” Pate said. “We can’t continue to manage something so precious based on a user capacity that was set in the 80s. But when the public hears the word ‘capacity,’ they immediately think that the goal of the plan is to restrict their right to access the river. That’s not the goal. The goal is to protect the watershed and promote stewardship.”

“Capacity tolerance can differ depending on the individual: Where are they from? How long have they lived here? Are they visiting from somewhere with a denser population?” Pate continued. “What’s important to remember is recreation is just one of many noted outstanding remarkable values that agencies have to protect. Uniquely unmanaged recreation can adversely affect a wide array of the river’s other protected outstanding remarkable values and water quality.”

Although the years-long delays that have buffeted the CRMP were unanticipated, Pate said it has given the group an opportunity to expand public outreach, including building initiatives to improve stewardship and launch numerous projects aimed at boosting both environmental and public safety. For example, FRA secured funding through Flathead Electric Cooperative’s Roundup for Safety Grant to recruit river ambassadors for the 2022 float season. It also hosted a Wild and Scenic River Webinar Series to bring members of the public up to speed about the CRMP’s progress and how they can participate.

“Our role is to help increase education, outreach and stewardship activities surrounding the Three Forks of the Flathead,” Pate said. “Even though one single individual can be a worthy champion of the resource and rightly so, it ultimately takes everyone working together to not only elevate recognition of the resource, but to be stewards and understand that there is such a thing as loving a place to death.”

For Diamond, the new generation of stewards can’t arrive soon enough.

Within days of his Friends of the Flathead River group filing suit, a pickup truck became stuck on the edge of the gravel bar and was partially submerged in the river, prompting a fleet of emergency vehicles to respond. Eventually, the truck was towed out, but Diamond worried that it portended a long summer of misbehavior.

“The message we have received is that the driving management principle right now is public access, but to what end?” Diamond said. “You can’t manage only for public access and still have a Wild and Scenic River. I don’t know how much more this watershed can tolerate.”