Call of the Loon

In Glacier National Park, volunteer citizen scientists help park biologists better understand loon breeding and population numbers while also creating advocates for the bird

By Sarah Mosquera

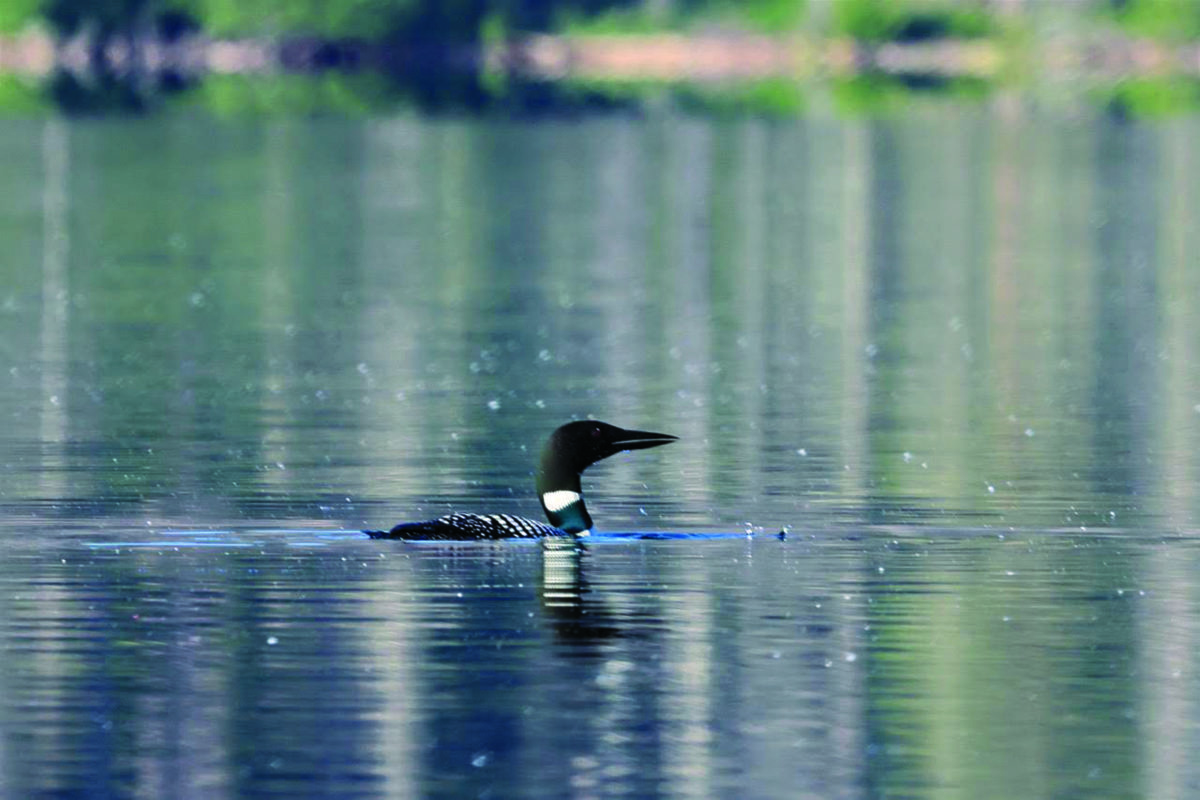

After a four-mile trek through overgrown thimbleberry bushes, Jessica Mejia and Tina Zenzola arrived at Mokowanis Lake in the Belly River of Glacier National Park. The two walked to the water’s edge and quickly spotted a pair of loons swimming in the middle of the lake. The birds’ speckled black-and-white plumage and iridescent black heads make them easy to spot.

With a closer look, the loons’ red eyes are evident – indicative of the breeding season. In a few months, the birds will return to their gray-and-white color pattern and the vibrant crimson of their eyes will fade to a dull reddish-brown.

Zenzola dropped her day pack and watched the pair through her binoculars as Mejia marked the sighting in the citizen science app on her phone. “It doesn’t look like these two have any chicks,” Zenzola noted.

Zenzola and Mejia are a part of the Common Loon Citizen Science Project in Glacier National Park, which began in 2005 to provide park biologists with a better understanding of Glacier’s loon population. Their trip was during the breeding season, and they hoped to find a pair of loons with chicks at one of their survey sites. Loons have slow breeding rates, and a pair will only have two eggs per season. Only six loon chicks are hatched in Glacier every year — of those, half will survive.

In addition to slow breeding rates, loons need a protected habitat to survive and produce offspring. With expanded access to remote lakes, humans are causing greater disturbances to loons, who must nest along the shoreline due to their inability to walk far on land. Loons evolved over one million years ago, making them well-suited for a specific environment, but unfortunately, this makes it difficult for them to adapt to environmental changes. Data gathered by citizen scientists help park managers better understand the threats to loon population health and how to best respond.

“I can’t gather all of this data alone,” Kelsey Cronin, who leads the project, said. “Citizen scientists make all of this possible.” Zenzola is in her fifth year as a citizen scientist and doesn’t plan to quit anytime soon. “We have some all-stars who have been with us for over 15 years,” Cronin said.

The citizen science project not only helps park biologists better understand loon breeding and population numbers but also creates advocates for the bird. “Citizen science makes it much more accessible,” Cronin said. “With more participants, there’s increased public outreach and more people who care about what’s going on with these birds.”

Zenzola and Mejia’s trip into the Belly was part of a greater statewide project called “Loon Days,” in which every Montana lake known as a loon breeding ground is surveyed. The project is a collective effort by the National Park Service, Fish Wildlife and Parks, the Forest Service, Department of Natural Resources and Conservation, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes and the Blackfeet Nation. Each department has its own citizen scientists who venture into the backcountry in search of loons, with high hopes of finding a pair with chicks.

The following morning, back at basecamp, Zenzola and Mejia packed up their tents near the waterline of Cosley Lake. As the sun slowly crept over the jagged peaks and the clouds settled just inches above the motionless water, a haunting cry cut through the silence: the wail of a loon seeking its mate. Mejia and Zenzola stopped to listen before venturing down to the water – they had seen a pair of loons on the lake just the day before, but now the loon’s cries went unanswered.