It was about 9 p.m. on a Friday night when the 160-pound-test nylon line on Leslie Griffith’s large fishing reel began to sing the opening stanza in what would become a colorful, controversial chapter in the lore of Flathead Lake. In the days that followed that evening in late May 1955, Griffith would unspool a fish story reminiscent of a Hemingway novel.

Described as a “freelance fisherman,” Griffith had been living near Dayton, on the lake’s west shore, lured by the hope of catching a large white sturgeon and claiming a reward offered by a group known as Big Fish Unlimited, an organization of Polson residents aiming to bring economically beneficial publicity to the community at the south end of Flathead Lake. A fish over 9 feet would net a prize of $500, while a fish greater than 14 feet long would yield a captor $1,000. Members of the group contended that sturgeon lived in Flathead, a belief fueled by multiple reported sightings, including one from J.F. “Fay” McAlear, a leader of Big Fish Unlimited, who told of seeing a large fish, possibly an 18-footer, in the lake in 1951.

Griffith, 63, who reportedly had caught a 300-pound white sturgeon in the Snake River in Idaho, took the reward bait. He had been fishing unsuccessfully for nearly three months before he snagged the big one near Cromwell Island in the lake’s Big Arm that May evening. The fish, he said, pulled all 600 feet of his line from the reel and towed Griffith, alone in his 16-foot cedar boat, around parts of the lake for five hours. At one point, the fisherman told of using a gaff, a device with a hook attached to a handle or pole, to contain the fish. Apparently missing vital organs, the gaff wound caused the big fish to thrash about violently, nearly causing the boat to capsize, Griffith told interviewers.

Later, the fisherman said he used another gaff to subdue the fish and towed it initially to a dock in Big Arm and eventually to Dayton, where he located a telephone. His first call, in the minutes after dawn, was to McAlear, the Big Fish promoter, who quickly drove to Dayton and with the help of Griffith and several others, loaded the fish into a truck and headed for Polson.

The events in May 1955 remain the only reported catch of a white sturgeon in Flathead Lake, although sightings of very large fish and even serpent-like animals stretch back centuries in native legend and in the more recent stories of white inhabitants. The singular status of what became known as the “Griffith sturgeon” has sparked fascination and skepticism that has endured for decades. But the story has also fueled an even larger legend: Could a white sturgeon, the largest fish known to exist in North America, be the legendary “Flathead Lake Monster?”

Mysterious “creatures”

While ancient Kootenai legend includes vague accounts of monster-like activity in the lake, possibly the first modern account to gain credence came in 1889 from James Kerr, the captain of the U.S. Grant, a steam-driven boat that ferried passengers and freight up and down the lake. Kerr reported seeing what he initially thought was a large log. As the boat got closer, the “log,” estimated at more than 20 feet in length, began to move through the water. Along with Kerr, many of the more than 100 passengers on the boat reportedly spotted the mysterious creature, which disappeared from the surface after shots were fired from a passenger’s rifle.

In the years to come, sightings of a monster of varying shapes and sizes came in waves. The tally of sightings grew over the years, many of them reported in the pages of the Flathead Courier, the weekly newspaper in Polson. Some accounts were sketchy, others came from sources that seemed credible.

The late Paul Fugleberg, the longtime editor of the Courier, and the author of numerous books about the history of the lake and its environs, chronicled many of the monster sightings. In a column in 2015, he summarized the nature of many reports: “Some of the sightings have been attributed to hyperactive imaginations, playful pranks, natural phenomena such as wave action, shadows, lighting effects, logs and a large number of animals, including bears, horses, deer, elk, dogs, a dead monkey, a loose circus seal and even an escaped buffalo.”

Despite the cynical tendencies of news reporters, Fugleberg never dismissed the possible existence of a monster of some sort in the lake and wrote on numerous occasions of the sturgeon hauled ashore by Griffith in 1955. He also shared a letter he received from noted Montana author Dorothy Johnson in 1962 in which Johnson urged caution in dismissing sightings. “I don’t think the monster should be done tongue in cheek,” she wrote Fugleberg. “You have eyewitness accounts by people who were scared and didn’t think it was funny. I remember hearing (about) something in Flathead Lake more than 40 years ago, so I don’t give the Polson Chamber of Commerce credit for dreaming it up.”

An avid reader of accounts of lake monster sightings?

Laney Hanzel worked for Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks as a Flathead Lake fisheries biologist from 1960 to 1993. Although Hanzel died in October 2022, he spent years compiling accounts and conducting interviews with folks who reported seeing large fish or other unusual animals in the lake. His obituary noted that Hanzel earned the reputation as “the world-renowned Flathead Lake Monster expert.”

Hilary Devlin, in her past work for the Flathead Lakers, the conservation group, spent a memorable afternoon with Hanzel as he shared some of the accounts and stories linked to the alleged mysterious lake dweller. She also worked with Hanzel to create a map of more than 100 sightings going back to 1889. The map, Devlin says, is among the most popular features on the Lakers website, flatheadlakers.org.

Hanzel didn’t like the “monster” label. “He called it a creature,” she says, noting the map denotes sightings of either a large fish or a creature. “When Laney told stories and talked about it, you weren’t sure if he believed it or not. He just presented it in a way that you could make up your own mind.”

Hanzel said some accounts painted a picture of a creature that vaguely resembled descriptions of a sea serpent or even the famed “Loch Ness” monster reputed to live in a Scottish lake. “Most, other than large fish sightings, describe it as long and eel-shaped, round, 30 to 40 feet in length with large black eyes,” he told Missoulian reporter Vince Devlin in 2017. “They say it undulates through the water like a snake.”

While Hanzel may have largely avoided sharing his opinion about a monster, or the possible presence of sturgeon in the lake, others of a scientific bent have expressed doubts. Despite extensive netting, electro-shocking, small submarines that have ventured deep into the lake and other types of research, including time spent underwater in the forks of the Flathead River, no sign of sturgeon or other creatures has been found.

“The odds of something like this going unnoticed are pretty slim,” Brian Marotz, a now-retired FWP biologist, told an interviewer in 2003. Noting the popularity of fishing for lake trout in the lake’s depths, “you would think that someone would pick up a smaller sturgeon after all these years.”

White sturgeon, the largest freshwater fish in North America, is native to several rivers in the Northwest that drain into the Pacific Ocean, including the Columbia River system, which includes, in its upper reaches, the Clark Fork and Flathead rivers. The big fish are found in Kootenay Lake in British Columbia and there is a small, isolated population of white sturgeon in the Kootenai River in northern Idaho and in the river below Kootenai Falls, west of Libby. Biologists believe the presence of tall waterfalls in rivers, and the later construction of hydroelectric dams, have limited the range of the white sturgeon in North America.

“There are lakes all over the Northwest that have sturgeon in them,” notes Polson resident Karen Dunwell, who serves as president of the Polson-Flathead Lake Museum. As the granddaughter of J.F. McAlear, the Polson businessman and Big Fish promoter, her interest in sturgeon may be genetic. “I was bitten by the sturgeon bug,” she says. “They are fascinating to me.”

Dunwell reports that her grandparents spotted sturgeon while fishing off Finley Point decades ago. Years later, she saw several sturgeon in the same area “and they were easily more than 10 feet.” At another point, her husband spotted smaller sturgeon in the area.

Acknowledging the scientific skepticism about sturgeon or other creatures in the lake, she notes that sturgeon can live for 80 to 100 years, are elusive and can appear to be serpent-like due to their smooth, sinuous skin that allows them to move gracefully through water. She harbors little doubt that the big fish live, or have lived, in Flathead Lake.

At the Flathead Lake Biological Station at Yellow Bay, scientists have studied the lake and its tributaries for more than a century. Tom Bansak, the station’s assistant director, says there are no clear answers to questions about sturgeon, although the idea of a prehistoric creature seems farfetched. In his view, the presence of white sturgeon in nearby waters and the oral histories of Indigenous people support the idea that the big fish could have lived in Flathead, a geological remnant of Glacial Lake Missoula.

“I think it is highly likely that sturgeon have lived in Flathead Lake or its predecessors,” Bansak says. “To me, the question is whether they still persist and whether we can document proof of their current existence.”

Big fish mania

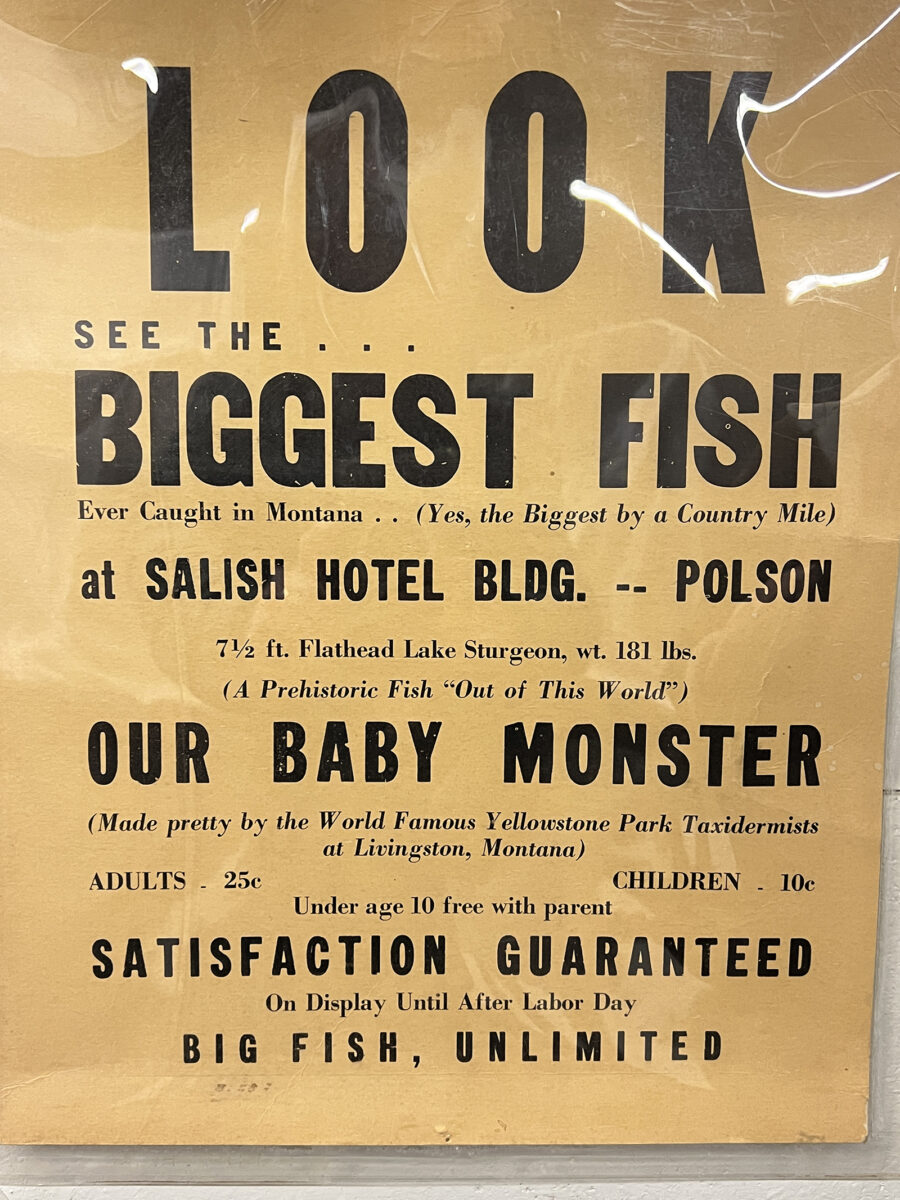

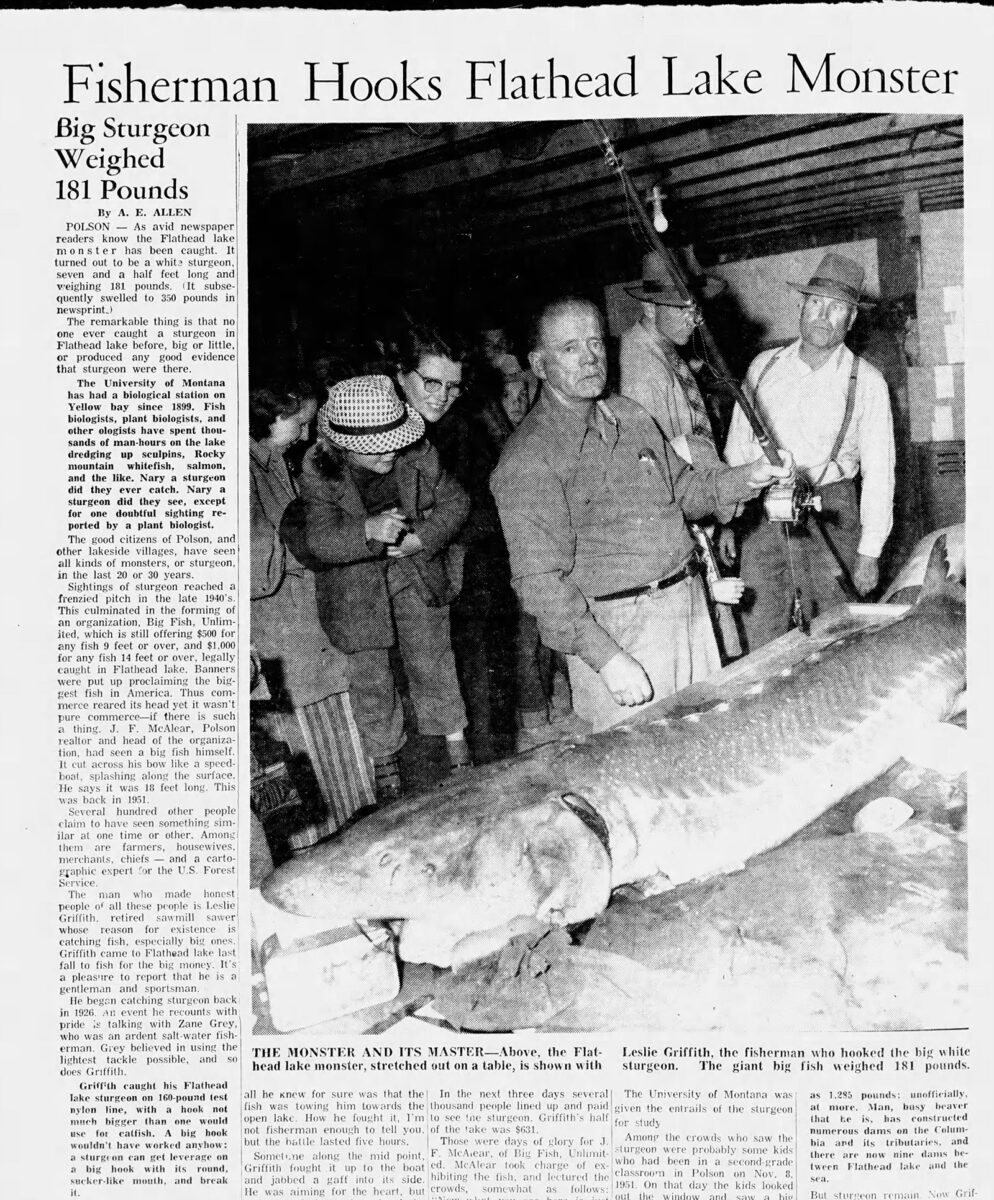

Within hours of its arrival in Polson, Griffith’s sturgeon began to make waves. McAlear and others arranged to have the fish, more than seven feet long, placed on ice and put on display in the Salish Hotel building, where it remained for several days. Viewers who paid 25 cents (10 cents for children) were invited to guess its weight. McAlear shared colorful commentary, noting that the Griffith sturgeon “was just a small fish. The big ones are still out there…we think we’ve got the world’s largest sturgeon out there.”

Promotional posters described the sturgeon as “our baby monster” and “the biggest fish ever caught in Montana.” Within a few days, McAlear reported that at least 7,000 people had seen the sturgeon in Polson and at Allentown, between Ronan and St. Ignatius.

The apparent catch was front page news across Montana and across the country. An account in the Great Falls Tribune, headlined “Fisherman Hooks Flathead Lake Monster,” noted that the fish weighed 181 pounds, although “it subsequently swelled to 350 pounds in newsprint.” The Tribune account also pointed out a critical fact: “The remarkable thing is no one has ever caught a sturgeon in Flathead Lake before, big or little, or produced any good evidence that sturgeon were there.”

Some began to question whether the fish was actually caught in the lake. It was possible, some speculated, that the sturgeon was brought to the area from elsewhere as part of a promotional scheme involving Griffith and Big Fish Unlimited. In response, McAlear and Griffith signed notarized statements stating the sturgeon was indeed caught in Flathead Lake. Promoters also came up with an additional reward, offering $1,000 to anyone who could prove the fish didn’t come from the lake.

Two scientists associated with the biological station and the University of Montana in Missoula were unable to answer the question of the sturgeon’s residency. Despite an examination of its innards later in the day it was brought ashore, zoologists Royal Brunson and Daniel Block said the viscera offered few clues about the origin of the 27-year-old sturgeon. But Brunson, who had done a 10-year study of Flathead fish, may have fanned the flames of doubt when he noted the presence of a fish backbone inside the sturgeon that didn’t appear to come from a fish known to be in the lake.

In the summer after the Griffith sturgeon surfaced, a number of residents and visitors reported spotting big fish in several parts of the lake, with some of the sightings reportedly involving a group of fish. Thain White, a well-known amateur historian and the operator of the Flathead Lake Lookout Museum south of Lakeside, reported watching a group of fish for several hours in September 1955. By his count, there were 36 sturgeon between 3 feet and 12 feet long in the group.

The sturgeon phenomena inspired additional anglers, including McAlear. Dunwell recalls spending many hours fishing for sturgeon with her grandfather, always plying the waters between Wild Horse and Cromwell islands, where Griffith said he made his catch. They used wire cable for fishing lines, a spool of which is on display at the Polson museum. She also recalls using animal blood supplied by a local butcher shop to chum the water.

While occasional sightings of a big fish or other creature were reported in coming years, the sturgeon mania appeared to cool, at least in the eyes of the public. But a simmering dispute between the fisherman and the Big Fish promoter eventually spilled into the legal arena. Griffith sued McAlear, claiming that he, not Big Fish Unlimited, was the rightful owner of the sturgeon, which had been mounted by a taxidermist, and that he was owed more money than the $698.48 he had received from its public display.

The case eventually landed in front of the Montana Supreme Court. More than four years after the sturgeon was trucked to Polson, the court in late 1959 confirmed that the sturgeon belonged to Big Fish Unlimited and while a more thorough accounting was needed, it ruled that Griffith was owed only half of the display proceeds.

The Supreme Court justices did not offer an opinion, legal or otherwise, on the origin of the big fish or whether other sturgeon or mysterious creatures lived in Flathead Lake.

State fishing records, kept by Montana FWP, make no mention of the Griffith sturgeon. A 96-pound white sturgeon caught by Herb Stout in 1968 in the Kootenai River is the official Montana record holder.

A mounted version of the controversial sturgeon, yellowed by the decades, hangs on the wall of the Polson museum, shrouded with questions about its colorful past. Dunwell enjoys the mystery that envelops the fish but doesn’t see any answers to the questions about the sturgeon, or other possible creatures, surfacing soon.

“You are going to have controversy about this forever,” she says.