Who is ‘Held’ of Held v. State of Montana?

Early exposure to scientific rigor and climate change’s impact on ranches led Rikki Held to confer her name to the nation’s first constitutional climate change lawsuit to reach trial

By Micah Drew

Rikki Held’s last name has been referenced in legal briefs, news articles and water cooler conversations for two years now, since the court case Held v. State of Montana was filed in Montana’s First Judicial District Court. Held was one of 16 youth plaintiffs who filed the 2020 lawsuit against several Montana government agencies, and its governor, alleging that the implementation of two energy-related policies is an infringement of the youths’ constitutional right to a clean and healthful environment. Since she was the only plaintiff of age when it was filed, it’s her name that will be forever attached to the decision made in the landmark case.

Held was brought to the legal table by a meandering path that runs through the heart of her family’s ranch. Held grew up on a 7,000-acre cattle ranch and saw the destruction of the land and her family’s livelihood caused by the changing climate — an experience she feels can be understood by the rural state’s ranching and farming communities.

“I think that ranchers see it in a different way, ranchers are on the ground every day,” Held said. “Maybe they aren’t having as many conversations about climate change necessarily, but they are seeing these changes with wildfires and are worried about the daily impacts of hay prices going up because of drought and losing cattle from water variability or fires.”

Between growing up on a ranch and a chance encounter with the world of scientific inquiry at a young age, Held charted a unique path to the courtroom. And while Held didn’t set out to become a climate activist, she felt compelled to act on behalf of her younger peers. Those who are too young to vote on the actions of the government look at the world through a different lens than their older counterparts, she says.

“As youth, we are exposed to a lot of knowledge about climate change. We can’t keep passing it on to the next generation when we’re being told about all the impacts that are already happening,” Held said. “In some ways, our generation feels a lot of pressure, kind of a burden, to make something happen because it’s our lives that are at risk.”

Before it was a legal reference, Rikki Held’s name was first published in the acknowledgments of a 2015 peer-reviewed paper in the scientific journal GeoResJ titled “Preserving geomorphic data records of flood disturbances.” Though Held was in middle school at the time, she is credited with helping U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) researchers survey cross sections of Montana’s Powder River, one of the longest undammed waterways in the West, which happens to pass through her family’s 7,000-acre ranch.

The Powder River begins in the Bighorn Mountains of Wyoming and flows north through Montana before joining the Yellowstone River between Miles City and Glendive. With no man-made modifications along the route other than some diversions to irrigate farmlands, Powder River provides a lengthy, natural, outdoor laboratory — a scientist’s dream. A study on the river that began in the 1970s has quantified the natural erosion, transport and deposition of sediments throughout the riverbed, and mapped changes to the river’s channel with specific focus on years of high flood or periods following nearby wildfires. Researchers have established 24 survey sites along a 57-mile stretch of Powder River, several of which are accessed through the Held family ranch.

Several scientific papers have come out of the study over the years. One documented the aftereffects of a major flood event in 1978 where as much as 65 feet eroded from sections of the river bank. Regular follow-up studies characterized sediment composition, erosion patterns and plant distribution along the river.

“Even when I was little I would go out with [the researchers] during surveys, just following them around and learning from them,” Held said, adding that she “got kind of caught up” in the science, which later led to internships and ultimately the mention in the 2015 paper. “I think that really got me interested in science, I was able to connect it back to my ranch, my home.”

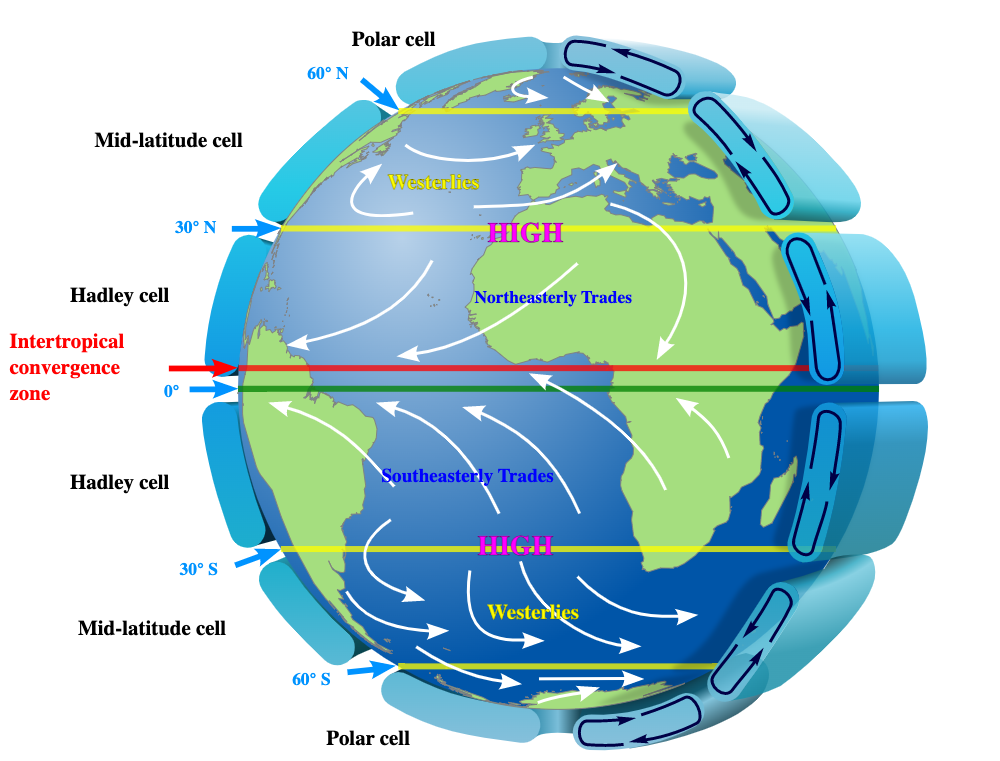

Throughout high school, Held gravitated toward the hard sciences. “I remember a wind pattern diagram with Hadley cells, and I just thought that was fascinating how things could be explained,” she said. “I got really interested in environmental science that way and learned about climate change in high school. I just knew that this is a really serious issue that we need to focus on.”

Held, now 22, graduated this spring from Colorado College with a degree in environmental science and is figuring out how to use her aptitude for environmental research to carve out a career path. Speaking about a recent NASA-funded study she contributed to, Held grew visibly excited as she described her work on “combining ecology and geomorphology to map out invasive Russian olive species.” She said she’s considering future studies in climatology or hydrology, something “about Earth processes where I can bring it back to the people and use science to help them.”

While Held was learning to survey stream widths and how Hadley cells circulate tropical air around the globe, she was also witnessing the effects of extreme weather events on her family’s livelihood.

The complaint states that in 2007 following several years of drought in southeastern Montana, the Powder River dried up, eliminating the water source for the ranch’s crops and livestock. A decade later, an early spring thaw flooded the river basin, nearly reaching Held’s house and eroding several feet of riverbank. Increased risks of major flooding events, such as the 2022 floods that damaged an entrance road to Yellowstone National Park, have been linked to global warming. One study published using the Powder River data also cites climate change as a contributing cause for the river’s changing migration rate over time.

The Held family has lost cattle to flooding events, an economic hardship for any ranch. On the elementally opposite side of the extreme weather spectrum, the Helds also lost a great number of animals in 2012 to starvation following a wildfire that burned through acres of grazing land. The fire took out miles of powerlines in the area, leaving the ranch without electricity for weeks. During another spate of nearby fires in 2021, Held recalls ash falling from the sky, dusting the ground for days and local schools were set up as shelters for families that had to evacuate their homes. The wildfire smoke, along with a record-breaking string of triple digit days that summer, didn’t keep Held inside — there was ranch work that couldn’t wait.

“When you’re in the moment, you have to just keep going with daily life, you have to do everything you can to keep up with the business or keep your livestock as safe as you can and figure out issues like how to get them water,” Held said. “It’s hard to think about it more broadly in terms of climate change … but from studying this, I know that we need to make some big systematic changes in what we’re doing to not continue down the route we’re taking.”

The increased effects on her family’s ranching lifestyle, along with her growing interest in studying environmental science in college, led Held to reach out to Our Children’s Trust when she heard about the potential lawsuit.

“When I was first learning about climate change in high school, I saw it as something on the other side of the world, like polar bears and ice melting or the coastlines with sea level rise,” Held said. “Living in the U.S., in a land-locked place I didn’t really think about how it affected me, even though I’d seen these changes while I was growing up.”

“Being part of this case, it’s been nice to put my own story into the broader climate change narrative and make the connections through science and observation of how my home plays into it,” she said. “Montana is a big emitter of fossil fuels and is contributing to climate change. I know it’s a broader global issue, but you can’t not take responsibility.”

Held doesn’t know whether she’d consider taking over the family ranch, saying she’s “unsure what the future will be there.” It’s a sentiment about the viability of the industry she thinks is shared by many farmers and ranchers in the state — indeed it’s her lived experience on the family ranch that she thinks will allow the lawsuit to resonate with a greater portion of Montanans who may not as readily engage in discussions of climate change

Across the state though, Held believes that Montana is still a place where residents value their neighbors and the land and resources they’re entrusted, making it a unique place for this lawsuit to play out.

“Those values could play into this conversation and make a change,” she said. “It’s important that this case is happening here.”

This article is part of a series on the youth-led constitutional climate change lawsuit Held v. Montana, which goes to trial in Helena on June 12. The rest of the series can be read at mtclimatecase.flatheadbeacon.com. This project is produced by the Flathead Beacon newsroom, in collaboration with the Montana Free Press, and is supported by the MIT Environmental Solutions Journalism Fellowship.