Nonprofits Warn of Rise in Food Insecurity After State Declines Millions in Federal Pandemic EBT Dollars

Local food banks say the end of the pandemic-era program in Montana will put thousands of Montana children at risk of going hungry while school is out

By Denali Sagner

The state of Montana last month announced that it would not accept federal funds through the Pandemic Electronic Benefit Transfer (P-EBT) program, a temporary initiative implemented by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) that seeks to fill gaps for families struggling with food insecurity.

According to estimates by the Montana Food Bank Network (MFBN), the decision to decline P-EBT benefits leaves $10 million in federal dollars on the table that could have been distributed to approximately 73,000 children to address food insecurity. While state officials cited the end of the pandemic and the administrative burden of overseeing the program as the reason for declining the funding, administrators of Montana’s network of food assistance programs warned of an uptick in hunger for Montana schoolchildren in the absence of the program.

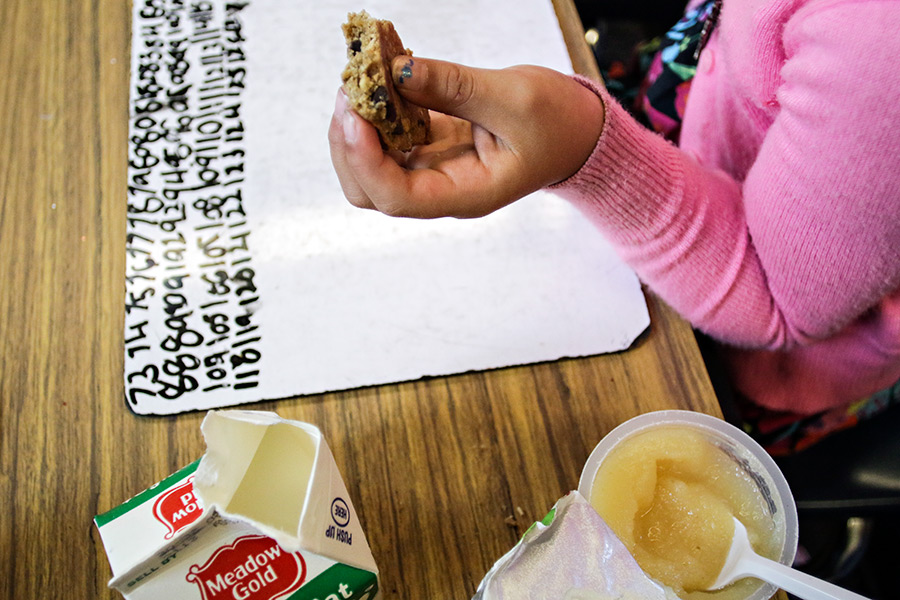

Through P-EBT, a program implemented by the USDA in 2020, school children receive EBT cards loaded with nutrition benefits, which can be used to purchase food at a variety of grocery stores. The federal government initiated the program to help families during pandemic-era school closures — as many low-income children had been receiving free breakfast and lunch at school. Despite the end of COVID-related school closures, USDA has extended P-EBT through the 2022-23 school year and summer 2023.

Thirty-two states and the District of Columbia participated in P-EBT for the 2022-23 school year, and 35 states, DC and two territories have enrolled for summer 2023, including North Dakota and Wyoming.

Yet Montana’s Department of Public Health and Human Services (DPHHS) announced last month that it will not accept the benefits for the 2022-23 school year or summer 2023, citing the administrative burden of doling out the funding to low-income families.

“The reality is the requirements of the P-EBT program are labor intensive for both school districts and DPHHS. The program does not follow traditional SNAP processes or rules. Instead, it requires manual processes for data integrity, quality control and benefits issuance, which is a significant administrative burden for what was meant to be a temporary program,” Jon Ebelt, DPHHS communications director, said in an email to the Beacon.

Ebelt also noted that P-EBT was intended to be a temporary pandemic-era program, and said that $13 million in the benefits remain unspent, as a number of families returned the funds because they didn’t understand why they received them or didn’t need them.

The administrative hurdles for DPHHS, Ebelt said, stem from the fact that the USDA does not allow states to only administer benefits to families already receiving SNAP, but rather requires states to identify and issue P-EBT to families not currently receiving SNAP dollars. Additionally, DPHHS does not have a team dedicated to staffing and distributing the program.

The decision to decline P-EBT for the 2022-23 school year and summer marks the latest development in a protracted fight between DPHHS and Montana’s network of food assistance programs, as the state has repeatedly refused to or attempted to refuse to extend the benefits.

“We certainly understand that a program like this is a lot of work to administer. At the same time, this department is designed to administer programs like this,” Wren Greaney, advocacy manager for MFBN, said. “The need that we’re seeing across the state for food assistance is really high.”

After distributing more than $66 million in P-EBT through the 2020-21 school year and summer 2021, DPHHS in early 2022 announced that it would not accept the benefits for the 2021-2022 school year and summer 2022, citing a more than 50% decrease in demand from fall of 2020. The department reversed course a few months later, after nearly 60 food banks and community groups petitioned the state to accept the tens of millions of P-EBT dollars.

Over the summer of 2022, northwest Montana’s Bigfork, Kalispell, Libby, Polson, Ronan, Seeley Lake and West Valley school districts participated in the program, receiving shares of the $3.6 million in P-EBT benefits distributed across the state between July and August of last year.

According to local food bank administrators, the program addresses a critical need for low-income families, specifically during the summer months when students are unable to access meals at school.

“Our biggest time for families with kiddos is really during the summer, when they’re in need,” Jamie Quinn, executive director of the Flathead Food Bank, said.

While Quinn acknowledged the administrative task of distributing P-EBT, the food bank director said that without the program, families across the rural Flathead Valley will be left with limited options when it comes to feeding their children during summer break.

While the USDA operates a free Summer Food Service Program (SFSP), where any child under the age of 18 can receive free meals, the program often fails to reach Montana’s most rural corners, where families can live miles from the closest SFSP site. For working parents who are unable to drive their children to the SFSP locations, the program can be inaccessible.

“There are kids who don’t have a place that they can walk to to go get food,” Quinn said about SFSP, “It’s not accessible to Kila, to Marion, to Fair Mont Egan.”

Sophie Albert, the executive director of the North Valley Food Bank in Whitefish, said that while the program is helpful in addressing summer food insecurity, accessibility issues can hinder its effectiveness in the area.

Albert noted that for families in Troy, the closest SFSP site is in Bonners Ferry, Idaho.

In addition to SFSP, food banks play a key role for low-income families during the summer in the absence of P-EBT. While the state is home to a vast network of food pantries, both Quinn and Albert said that they will not be able to make up for what is lost with the lapse of P-EBT in Montana.

“The state not approving these benefits really puts an additional burden on us,” Albert said.

Both the Flathead and North Valley food banks have seen an increase in demand and decrease in donations in recent years. Quinn said that at the Flathead Food Bank, working household visits per month rose 103% between 2021 and 2022, and food purchasing rose 78.7% due to a drop in donations.

“There’s nothing like P-EBT, so it is a huge loss,” Greaney said.

A complete list of Summer Food Service Program sites in the Flathead Valley can be found here.