‘One of the Most Bizarre and Obscure Chapters of Modern Warfare’

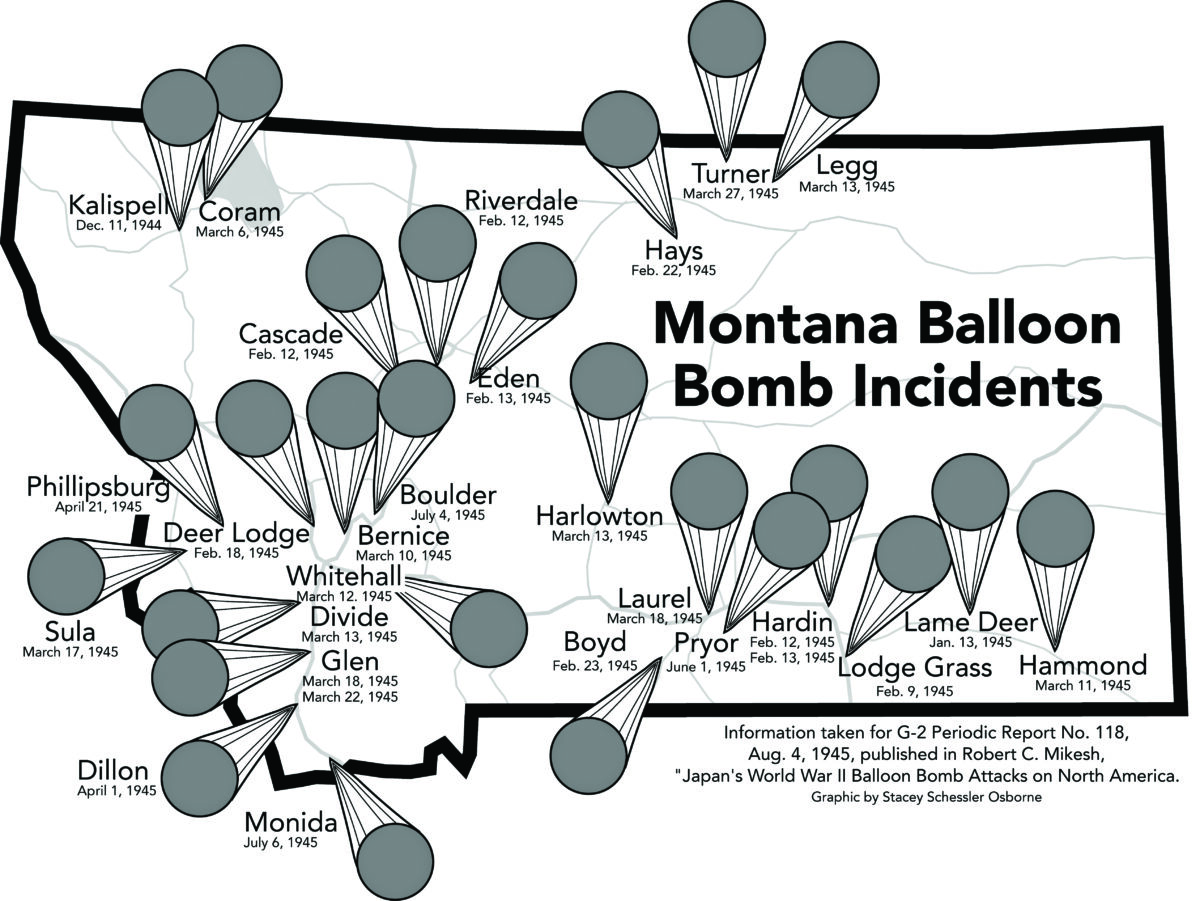

Historians estimate that Japan launched about 9,300 balloons at the height of World War II, each carrying about 800 pounds of bombs. About 300 were sighted or found in North America, with 32 balloon bombs turning up in Montana, including one in Kalispell.

By Butch Larcombe

Editor’s note: A Chinese balloon drifted over Montana (and later across much of the U.S.) in late January and early February of this year created an international incident. But the balloon, eventually shot down over the Atlantic Ocean, was far from the first foreign balloon to make its way to Montana.

On a cold early winter day in December 1944, Oscar and Owen Hill, father and son, were cutting wood in the Truman Creek area about 17 miles southwest of Kalispell when they discovered what at first appeared to be a cream-colored parachute. The object, later determined to be a balloon, featured Japanese writing and a rising-sun symbol.

The Hills notified Flathead County sheriff Duncan McCarthy, who gathered the balloon the next day and stored it in a garage. The sheriff also summoned federal authorities, who came to the Flathead to investigate.

News of the balloon discovery understandably sparked curiosity and the local rumor mill. Some accounts say that more than 500 area residents were able to view the balloon stored in the garage. The first local news account of the find came on the front page of the Western News, the weekly newspaper in Libby, on Dec. 14, 1944. The source of the news was a local mail carrier, who had heard it from a Kalispell-based mail carrier. According to this hearsay version, the large balloon didn’t have a basket “but in its place was a bomb which had failed to explode when the balloon came to earth.”

The story delivered by the mail carriers also noted “that secret service men were working on the case” and that “it has been impossible to obtain further confirmation of the story.”

The federal authorities, who were actually with the FBI, were tight-lipped. And shortly after the discovery of the apparent balloon bomb near Kalispell, the federal “Office of War Censorship,” established after the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, asked the news media to not publish accounts of the balloon bombs, claiming sharing such news would help the Japanese.

An Associated Press account of the Flathead discovery appeared in several newspapers across the U.S., but for months, even as remnants of additional balloon bombs were found not only in Northwest Montana, but across the state and nation, there was very little public mention of the incidents.

Even in the Flathead, where hundreds had seen the balloon bomb found in the Truman Creek area, talk was sparse. L.D. Spafford, the publisher of the Daily Inter Lake, offered this explanation to an interviewer: “Everybody was mighty interested, but when the Federal Bureau of Investigation warned not to discuss it, the whole town clammed up. There are too many people with sons and husbands in the service to take a chance on perhaps giving valuable information to the enemy.”

This voluntary wartime censorship extended beyond the balloon bombs. Newspapers and radio stations cautiously shared news of the war, much of which was supplied by the federal government itself.

It was well after the end of the war in 1945 that federal and military officials declassified documents that revealed the extent of the Japanese use of balloon bombs. It is estimated that Japan launched about 9,300 balloons, all about 33 feet wide, each carrying about 800 pounds of bombs, incendiary devices and ballast. Of that number, about 300 were sighted or found in North America. In Montana, 32 balloon bombs have been discovered. In some cases, the balloons were largely intact, while in others, only fragments or small pieces were found.

Southwest of Kalispell, authorities recovered the balloon’s envelope, pieces of its rigging and some apparatus. Officials estimated that balloon had been manufactured in late October 1944 and was launched from Japan between Nov. 11 and 25, 1944. That Truman Creek balloon was just the second found in the continental U.S. The first came when a balloon bomb exploded about a week earlier northwest of Thermopolis, Wyo.

Later, what was believed to be a balloon bomb was spotted drifting east of Bigfork in February 1945 and paper fragments were found floating in Flathead Lake that same month. A month later, paper fragments from a balloon were discovered near Coram, east of Columbia Falls.

Historians believe that Japanese schoolchildren helped manufacture many of the balloon envelopes, which were made of layers of lightweight paper sealed together with wax-like substances. Along with bombs, the airships were fitted with barometers linked to sand bags. When the balloons descended too low, sand bags were released, allowing them to gain altitude.

The unmanned balloons, filled with hydrogen, had no propulsion system, instead relying on the narrow band of westerly winds to carry them across the Pacific at altitudes of 20,000 to 40,000 feet and at speeds of more than 200 miles per hour. Relying on what is commonly known as the “jet stream,” aviation expert and former Smithsonian official Robert Mikesh, who did extensive research into the development and use of the balloon bombs, described the device as “the first successful intercontinental weapon.”

Helena-based historian Jon Axline used more vivid terms for the early balloon bombs, including the one found near Kalispell, describing them as “the vanguard of an aerial attack on the United States by Imperial Japan as World War II wound down.”

Some believe the incendiary devices on the balloons were intended to start forest fires in the Pacific Northwest, prompting the U.S. military to shift manpower to fight the fires and possibly impede the development of weapons. Another likely motive behind the balloons? The desire to spark fear.

With findings of balloons or related fragments stretching across the U.S. from Alaska to Michigan, and in Canada from British Columbia to Manitoba, Montana trails only Oregon in the number of known balloon-bomb incidents in the U.S.

Launched primarily in the cold, wet months spanning a roughly six-month period late in 1944 and early 1945, the airborne weapons riding the shape-shifting jet stream are believed to have started just two small brush fires and have caused a temporary power outage at a nuclear plant near Hanford, WA, where work on components for the nuclear bomb were taking place.

But on May 5, 1945, an incident near Bly, in southwest Oregon, altered the historical course of the balloon-bomb saga. A group of seven — two adults and five children on a Sunday school outing — discovered what was believed to be a balloon bomb. Moments after Elyse Mitchell called out to her pastor husband, Archie, who was nearby parking their vehicle, “Look what we found, dear,” the device exploded. Along with killing the five children, the blast also claimed Elyse Mitchell, who was five months pregnant.

The six deaths are believed to be the only World War II-related civilian deaths on the U.S. mainland. It was later learned that the Japanese had stopped launching the balloon weapons about a month before the Oregon deaths.

Almost two weeks after the deadly explosion, the U.S. government issued a vague statement about the event and warned people of “the danger of tampering with strange objects found in the woods.”

While Mikesh and other historians later noted that the voluntary censorship of news about the balloon weapons made it difficult to warn the public about the explosive objects, government officials defended the practice, saying the lack of news coverage about the impact of the balloon bombs “had baffled the Japanese, annoyed and humiliated them, and has been an important contribution to security.”

In an Associated Press interview after the end of the war, Japanese officials involved in the balloon program said they had been monitoring U.S. radio broadcasts as a way to measure the effectiveness of the bombs. The news blackout led them to conclude “that the weapon was worthless and whole experiment useless.”

While a significant number of the 9,000-plus bombs launched by the Japanese likely never reached North America, uncertainty remains as to whether there are more unexploded wind-driven weapons lingering in the woods.

In 2014, near Lumby, British Columbia, the Canadian province that borders much of the Flathead, a military bomb squad was called to detonate a balloon bomb found by forestry workers. In 2019, 75 years after the discovery of the mysterious balloon outside Kalispell, a man hunting mountain goats discovered the remains of another balloon bomb above the province’s remote Rausch River.

The discoveries, and the possibility of more to come, add intrigue to what Michael Collins, director of the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum in the 1970s, described “as one of the most bizarre and obscure chapters of modern warfare.”