Low Water Levels Threaten Crop Yields; Tester Latest Official to Seek Federal Intervention

Regional drought conditions have left Flathead Lake and local streamflows at historic lows for July as farmers grapple with agricultural losses

By Micah Drew

Historically low river and lake levels in northwest Montana stemming from a rapid melt out of the region’s snowpack are threatening agricultural business in Flathead County.

On July 5, the water level on Flathead Lake had reached an all-time low for this time of year, according to U.S. Geological Survey data, with surface water levels falling to 2,891.451 feet, or 18 inches below the dam-controlled lake’s full-pool mark. The low lake level, combined with historically low discharge levels along Flathead River, is impacting the ability for local farmers to irrigate their crops.

“For more than 20 years I’ve rented ground and grown fields of potatoes, but I’ve never had anything like this happen,” said seed potato farmer Steve Streich. “I need to irrigate for another six weeks at least and there’s not a chance of there being that much water left.”

Streich is one of a half-dozen farmers that pulls water from Egan Slough to irrigate crops. The slough, located along the Flathead River south of Kalispell, is fed by the river through a headgate. However, the slough can only fill when Flathead Lake backs up the river to where the surface elevation allows for a diversion from the main channel.

During normal years, the river runs roughly 14 inches higher than the slough, allowing farmers to regulate inflow, according to Charles Jaquette, who farms potatoes and grains in Egan Slough. This year, water levels recently hit equilibrium before reversing course, beginning to drain back into the river.

Jaquette estimates more than $350,000 worth of crops are in jeopardy, while Streich said one-fifth of his are likely to be lost if nothing changes.

“I’ve called every single official, spoken to staffers with all the congressmen, county commissioners, the governor,” Streich said. “I just hope someone can rattle enough bars to do something to help us.”

U.S. Sen. Jon Tester, D-Mont., became the latest public official to reach out to federal agencies requesting intervention to mitigate the effects of the regional drought.

According to the senator’s office, Tester had a phone call with Bureau of Reclamation (BoR) Commissioner Camille Touton on Thursday and followed that up with a letter requesting the bureau take actions on “workable solutions for impacted Montanans.”

“I am hearing directly from Montanans in the region that the low water levels are threatening the livelihood of Montana small businesses,” Tester wrote. “These businesses range from farmers who need to irrigate a crop, marina owners who may not be able to keep boats in the water, and hospitality leaders who serve the thousands of visitors that flock to Flathead Lake each summer. These agriculture and outdoor recreation jobs are the backbone of Montana’s economy, which is why it is critically important to act.”

Low regional snowpack this winter and historically fast snowmelt in May resulted in the Flathead basin water supply at near-record lows. According to the National Integrated Drought Information System, 94.71% of Flathead County is in drought, with nearly 65% categorized as severe drought. An estimated 31,610 acres of hay, 21,645 acres of wheat and more than 5,000 cattle are in drought conditions.

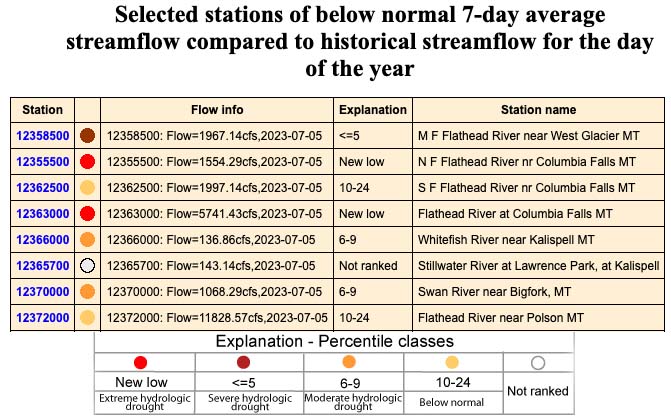

In addition, streamflow along the Flathead, Whitefish and Swan rivers are registering between moderate and extreme drought levels, with weekly streamflow averages along three stretches of the Flathead Fiver setting all-time lows.

The amount of water in the river basin is visually evident in Flathead Lake, where surface levels dropped to 2,891.45 feet on July 6, more than six inches lower than the previous record for the day. This marks the first time the lake has not been kept at full-pool since the Seli’š Ksanka Qlispe’ (SKQ) Dam, which controls the lake’s outflow, was built in 1938, according to Brian Lipscomb, CEO of Energy Keepers Inc., the corporation that operates the dam.

“This is the first time ever that this has been experienced since the facility was built,” Lipscomb said, attributing the historic water levels to climate change. “The dam holds the lake at full pool. If it wasn’t for our facility, the lake would draft down until the natural channel restriction at Polson stopped it, around eight feet below where it is.”

Lipscomb said the forecast is that Flathead Lake will stabilize around 22 inches below full pool, which, in addition to impacting recreation and business that depend on the water, has also greatly diminished the dam’s power generation.

The SKQ Dam operates under a license by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. That license has no contractual or legal obligations to maintain the lake’s full pool level, but does include strict parameters governing outflow below the dam to the lower Flathead River. From May 16 to July 15, minimum flows of 12,700 cubic feet per second (cfs) must be maintained to ensure enough water is provided for downstream irrigation and aquatic species, regardless of the lake’s surface level. Beginning July 1, SKQ operators began decreasing the dam’s output, which will continue until Flathead Lake reaches equilibrium around July 12. Under the operating license, outflows can only be reduced by 420 cfs per day.

With several days to go before Flathead Lake stabilizes, government officials including the Flathead County Commissioners and additional members of the state’s congressional delegation have floated the idea of releasing water from Hungry Horse Reservoir to recharge Flathead Lake and prevent further impacts to recreation, business and agriculture.

U.S. Rep. Ryan Zinke, R-Montana, wrote a letter to the BoR commissioner last week requesting a decision to increase outflow through Hungry Horse Dam, despite the reservoir sitting several feet below full pool.

While Zinke’s office indicated they believed the commissioner could make a unilateral decision, major operational deviations at any of the more than 60 federally operated dams throughout the Columbia River Basin require a multi-agency consensus. Dam operations are overseen by a Technical Management Team (TMT) comprising representatives from four states, BoR, Army Corps of Engineers, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Bonneville Power Administration and six tribal nations.

Members of the TMT must submit a proposal to deviate from a current water management plan to the full team for consideration, and then a recommendation will be made to the agency in charge of a specific dam — in the case of Hungry Horse Dam, the Bureau of Reclamation.

Following the conversation with the BoR Commisisoner, Tester said in a statement that the bureau is “standing by to swiftly act” on forthcoming recommendations from the TMT for potential mitigation options.

Hungry Horse Reservoir is currently sitting roughly 6 feet below its full-pool level, but can operate as far down as 20 feet below during low-water years.

According to water supply forecasts issued by the Natural Resources Conservation Service, inflows to Hungry Horse Reservoir this summer are the second lowest on record, which could limit how much the reservoir could be drawn down this early in the year. Agencies must balance requirements to provide minimum streamflow to the Flathead River for the remainder of the summer to ensure sufficient fish habitat, as well as meet power generation needs.

“It’s not just recreaters getting hurt, it’s people with real financial interests,” Streich said. “I just wish we could get some water.”