Can Short-Term Rental Data Shine a Light on the Tourism Season?

Insights from regional data shows AirBnB, Vrbo bookings in Whitefish city limits have dropped this year, though Flathead County continues upward trend, while businesses report “softer” summer

By Micah Drew

A viral video on social media last month claimed the bottom had fallen outof the short-term rental market. The purported “AirBnB crash” zeroed in on the Kalispell area as one of the top problem areas, alleging a nearly 50% decline in revenue reported earlier this year.

Sam Randall, an AirBnB spokesperson, said the viral claim was inconsistent with the company’s own data, which showed more guests using the vacation rental platform during the first quarter of 2023 than ever before.

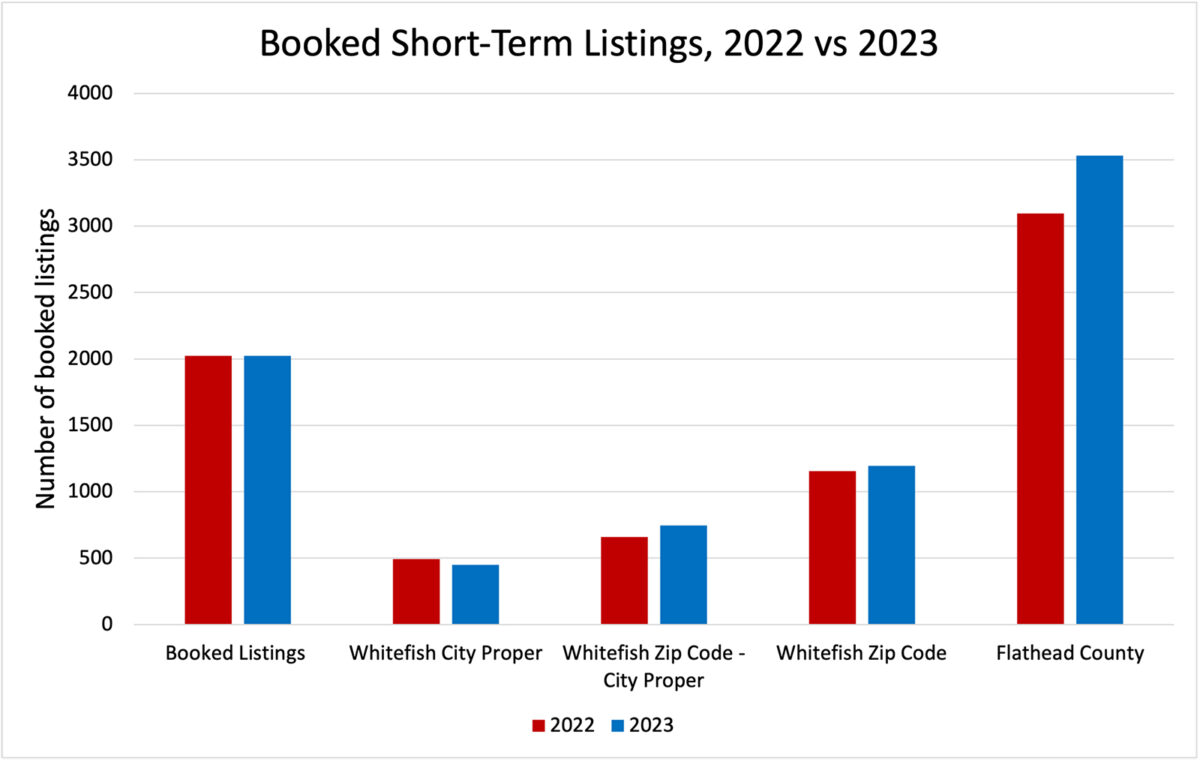

To back that up, data from AirDNA, a company that analyzes listing data in the short-term rental sector, reveals that the number of May and June listings in Flathead County increased by 12%, with bookings increasing by 6% and 14%, respectively, and revenue increasing by 2% in May, but dropping 6% in June year-over-year.

“2021 was a record year for the industry, and it was kind of a Covid anomaly, so we’re kind of coming off of those highs,” Jamie Lane, AirDNA’s chief economist, said in a CBS interview specifically addressing fears of a market collapse.”

A 2021 study by the University of Montana showed that Flathead County leads Montana in the number of short-term rental listings with 2,814 units, followed by Gallatin County with 2,524 listings. Those numbers continue to grow — last month, Flathead County had 3,345 total listings, nearly half of which were in the Whitefish zip code.

Despite the county’s overall increase in short-term rental business, not every segment of the county is equal in the eyes of the visitor. According to AirDNA, the city of Whitefish saw a marked decline in listings, bookings and revenue in recent months, though still not rising to the level that analysts would consider a “market crash.”

Zeroing in on the hyperlocal data, Julie Mullins, executive director of the Whitefish Convention and Visitors Bureau, also known as Explore Whitefish, said there’s been a clear drop in occupancy rates in recent months — 12% last quarter — which she believes has contributed to many businesses in the city feeling that the tourist season is more manageable this year.

“The chaos of Covid, that sense of urgency the last few years where everyone wanted to book their stays, and do so really far in advance, we’re not really feeling it this year,” Mullins said.

Despite anecdotal evidence of tourism season’s softer landing, Mullins does note that different methodologies for parsing data can provide vastly different interpretations of the short-term rental picture

For one, there’s a difference between occupancy rates, an oft-reported statistic to gauge the health of the tourism economy, and actual booked listings. While a hotel doesn’t fluctuate in the number of rooms and can use occupancy as a standard metric, short-term rentals can regularly be taken online or offline, causing year-over-year market fluctuations that don’t speak to a consistent occupancy trend.

So, while Flathead County as a whole registered a 14% increase in June bookings compared to last year, occupancy rates declined 4.4% — the discrepancy explained by the more than 400 new short-term rental listings in the county this year, causing inventory to swell and thus resulting in the rate of decline.

While those factors position bookings as the more accurate metric to portray the industry’s health, market experts say there’s another facet to examine in order to form a complete picture — hyper-specific location data.

In Whitefish, the inventory of short-term rental units within the defined city limits is only a fraction of those available across its greater geographic zone as defined by the 59937 zip code — 478 in the city out of a total of 1,261 units.

For example, in June, Flathead County bookings jumped 14% while bookings in Whitefish city limits dipped 10%; however, bookings in the greater Whitefish area, excluding city limits, increased by 13%. Using that formula, Whitefish’s overall bookings increased by 3.6%.

Another data set AirDNA provides are “pacing” forecasts, which essentially examine supply-and-demand numbers several weeks into the future and compare that projection to the same periods in previous years. Looking forward, projections for the entire Whitefish area reveal bookings through the end of August are down between 9% and 28% compared to this time last year. The data shows visitors planning trips to the area have booked 12% fewer nights than they had by the end of July in 2022.

Indeed, since mid-May, booking rates in Whitefish lagged behind 2022 figures for most weeks, one notable exception being the Under the Big Sky music festival.

Broadly speaking, Mullins thinks there’s likely been a bit of an overcorrection in the short-term rental market, at least in the Whitefish area, as well as a shift in how travelers are planning their vacations. With the post-Covid rush to travel continuing to die down, visitors are making plans on a more short-term basis, rather than booking trips months in advance.

She added that the traditional lodging industry hasn’t experienced a decrease in demand this year. For example, June’s occupancy rate for traditional lodging was 72.4%, which is essentially flat when compared to last year. This might indicate a shifting trend of visitors opting for traditional lodging over an AirBnB or Vrbo, which Mullins said have become increasingly more expensive — the average daily rate for a traditional room is around $200 in the Whitefish area, compared to an average of nearly $500 for a short-term rental.

“While we are seeing that decline in the short-term rentals in recent months, our traditional business partners are having a strong year,” she said. “It also is causing a bit of a softer experience in Whitefish. We just aren’t seeing quite the volume we had last year.”

Casting a wider data net to gauge the region’s visitation helps paint a slightly clearer picture. In June, 494,432 visitors passed through entrance gates of Glacier National Park, the region’s biggest tourist draw, a 6.6% decline over last year. Outside the park, local outdoor companies have also reported a slowdown to the summer’s pace of business.

“We really enjoy having a busy town, and our business partners need these months to sustain them throughout the year, but at the same time our residents have been very vocal that we have enough visitors in the summer,” Mullins said, adding that Explore Whitefish stopped actively promoting summertime visitation a few years ago, pivoting instead to their “Be a Friend of the Fish” sustainable tourism campaign.

No matter how you splice the data, Mullins says the overwhelming consensus in the area is that of a more manageable summer.

“As long as our business partners are doing well, it’s nice to see that we aren’t exceeding our capacity with visitors,” she said. “It’s really helping to create a more positive experience for our residents.”