‘Save Flathead Lake’ Group Demands ‘Truth’ Over Depleted Water Levels

During a series of four meetings promoted by the Flathead County Republicans, organizers challenged scientific consensus on the region’s historic drought and placed blame on Tribal dam management practices

By Micah Drew

On Aug. 4, a Lake County citizen action group called “Save Flathead Lake” held a meeting in the basement of the Kalispell Eagle’s Club to discuss the impacts and causes of Flathead Lake’s historically low lake levels, which on Aug. 8 sat nearly 30 inches below the traditional full-pool elevation maintained for summertime recreation and irrigation. The depleted lake levels recently prompted a natural disaster declaration for the region as waterfront businesses and agricultural producers grapple with the economic consequences of drought and elected leaders make appeals for federal relief.

Organizers of “Save Flathead Lake” have pushed back on much of the hydrological reasoning behind the steep drop in water storage, however, and during last week’s meeting they challenged the scientific consensus while placing blame on the operators of the Seli’š Ksanka Qlispe’ (SKQ) Dam.

One of a series of four gatherings held in the region over the last week, it was promoted by the Flathead County Republican Central Committee and hosted by Dr. Annie Bukacek, a Public Service Commissioner who gained notoriety as a leader in the local anti-vaccine movement after she joined the Flathead City-County Board of Health in early 2020. She resigned from that position in April 2022 to pursue a bid for the state’s utility regulator, though she said her role facilitating the “Save Flathead Lake” meeting was as a private citizen.

“I am disinclined to believe that the low level of Flathead Lake is due to climate change,” Bukacek said at the top of the meeting while introducing Linda Sauer, a retired healthcare administrator who led the discussion. “It is the job of people to take measures such that drought and floods don’t negatively impact us and when people don’t do their job properly, events like low lake levels are bound to happen.”

Sauer’s presentation centered on what she described as the “dueling explanations” of the low lake levels, which she suggested were worsened by a multi-agency decision to reject calls for the release of additional water from Hungry Horse Reservoir — a strategy that both local and statewide elected leaders proposed to offset the slumping flows to Flathead Lake — as well as the “willful mismanagement” of SKQ Dam by the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes (CSKT).

“The bottom line is we don’t know the truth yet,” Sauer told the more than 60 meeting attendees. “We’re going to find out the truth. We have to demand it as citizens.”

Sauer shared two U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) hydrographs depicting the levels of Flathead Lake and the outflows from SKQ Dam to the Flathead River, including when dam operators ramped up outflows in mid-May. Sauer compared the strategy to attempting to fill a bathtub with the drain open, even as the graph revealed that the lake level had continued to rise throughout May.

USGS data shows that the main stem of the Flathead River reached a peak flow of 35,500 cubic feet per second (cfs) on May 6, while SKQ dam was releasing just 10,900 cfs the same day. Indeed, there were only six days in May where outflows exceeded Flathead River inflows. In addition, the Swan, Whitefish and Stillwater rivers feed into Flathead Lake, further augmenting inflows, which, this year, were scant.

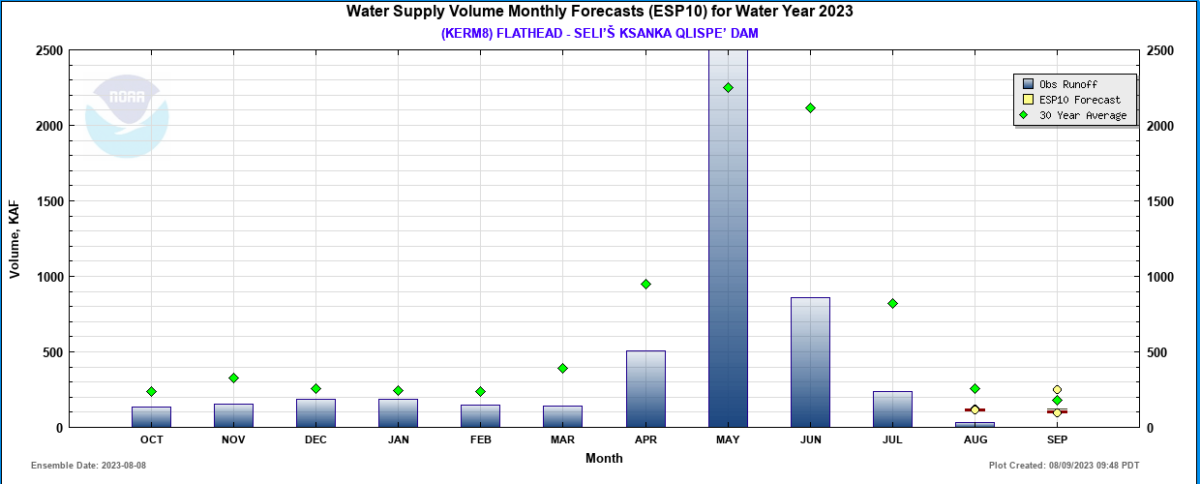

Brian Lipscomb, the CEO of Energy Keepers Inc., the CSKT corporation that operates SKQ Dam, told members of the Montana Legislature’s Water Policy Interim Committee (WPIC) on July 24 that “in 74 years of record keeping this is a new record low for water supply coming into the lake.”

“River flows going out of the facility are at the absolute minimums per our federal license,” Lipscomb said during his presentation to lawmakers, describing this year’s water-supply challenges as a direct result of climate-induced environmental change. “That’s 49 percent of average and it’s 36 percent of the flows that we released last year on the same day. So, quite a phenomenal shift from last year to this year.”

For Sauer, however, “climate change is the weakest argument” for the low lake levels. She cast doubt on data that draws a direct correlation between the depleted inflows to Flathead Lake and last winter’s record-low snowpack and rapid spring melt-out in the region, and she shared an interview featuring Kate Vandemoer, an outspoken opponent of the CSKT’s water rights compact that was ratified in 2020, who claimed that the CSKT had released the equivalent of 2 feet of water from Flathead Lake.

Speakers at the meeting further alleged that Energy Keepers released the excess water in May to sell power to out-of-state companies, though Lipscomb said the dam’s power generation is significantly lower that normal.

Repeatedly, Sauer and other attendees emphasized that they had nothing against individual tribal members, but instead were speaking out against the tribal government and specifically the water rights guaranteed in the CSKT Water Compact.

The Water Compact reserves a right to a maximum 229,383 acre-feet of water for the CSKT to utilize throughout the year from the Flathead Basin. The water right can only be used in accordance with a 2012 study that models how the depletion would affect both Hungry Horse Reservoir and Flathead Lake. Under the models, the water would be drawn from the Flathead Basin throughout the year, with the majority coming during July, August and September. The “most extreme effect” of the annual diversions, occurring only during the lowest 3% of water years, was estimated to alter Flathead Lake by just .4 feet.

Energy Keepers is responsible for controlling the top 10 feet of Flathead Lake, which amounts to 1.2 million acre-feet of water storage. Under normal operating procedures, the dam-controlled lake drops to its lowest point by April 15 to provide flood control across the region, then rises to 3 feet from full pool by Memorial Day, hitting full pool around June 12. The goal is to then operate in the full-pool range through Labor Day, but there is no legal requirement to do so in the 38-page Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) license for SKQ Dam.

In addition, a 2009 Montana Supreme Court decision in Mattson v. Montana Power Company quotes PPL Montana, which owned the dam prior to the CSKT, stating there is “no term in the license,” nor additional FERC requirements, dictating the lake must be maintained at full pool elevation.

The FERC license, which was jointly granted in 1985 to the Montana Power Company and the CSKT to operate the facility, does include strict minimum-outflow requirements for the lower Flathead River. Energy Keepers has been operating at those minimum outflows since the beginning of June, when the region’s forecasted water supply warned of a precipitous summertime drop-off.

“We identified this early. We saw it right out of the blocks,” Lipscomb said in his explanation to members of WPIC. “We started working with the Army Corps of Engineers and got relief from having to evacuate the lake and we began to refill the first week of March, six weeks early. Then we got relief from flood control and we filled the lake on May 30 to over 2 feet above normal.”

However, those proactive measures were not enough to offset the diminished inflows, Lipscomb said.

“When you have minimum inflows that are less than your outflows, the giant bathtub starts to go down,” he said. “And that is exactly what’s happened.”

While rare, this is not the first year Flathead Lake dropped below full pool. In 1940, just two years after the dam’s completion, the lake barely crested 2,891 feet. In 2001, another major drought year, Flathead Lake peaked at 2,892.67 — a lower peak than this summer — and by July 7 was down more than a foot from full-pool elevation. In 2015, the lake was also held roughly a foot below full pool during late summer.

The Save Flathead Lake meeting ended with Sauer urging residents along the lakeshore to document damages to their property, with the goal of creating a quantifiable database in the event of future legal actions.

“This has to become a Flathead Bud Light moment,” said Dr. Al Olszewski, the chair of the Flathead County Republicans, referencing a national rallying point for conservatives over the beer brand’s supposed ‘woke’ associations. “Otherwise, you’re going to find we will be looking at Flathead Lake like Flathead Reservoir, going up and down and up and down. It’s time to say we will not drink this ‘Bud Light.’”

On the same Friday as the meeting at the Kalispell Eagle’s Club, Jim Elser, director of the Flathead Lake Biological Station, fielded questions about the environmental factors contributing to the low lake levels during an open house at the research station’s home on Yellow Bay. According to Elser, operational changes at either SKQ or Hungry Horse dam probably wouldn’t have affected the outcome.

“Making decisions at either dam is complicated, but I don’t think changing anything would have mattered this year. There’s simply just no water in the basin,” Elser said in an interview, noting that the Flathead Basin’s water supply has been at an unprecedented deficit since January compared to the 30-year average. “We had low snowpack, we had a record speed of snow melt and the river is running at 60% of normal. You can look at the drought maps — we’re in a severe drought and no one’s making that up.”

“If you take all the missing water in the basin from January until now and compare that to what we normally get each month, it’s enough water to add a foot to Flathead Lake 17 times over,” he continued. “We just don’t have it.”