As Grizzly Bear Train Mortalities Spike, BNSF Mitigation Funds are Years Overdue

Another spate of train-caused grizzly bear deaths in northwest Montana has drawn attention to an overdue federal conservation plan that includes $2.6 million in funding from BNSF Railway to mitigate bear-human conflicts on the landscape

By Tristan Scott

On Sept. 18, Justine Vallieres was setting traps to capture a pair of food-conditioned grizzly bears breaking into cabins up the North Fork when she got word that a third bear, also a grizzly, had been killed on the train tracks near Stryker, clear across the Whitefish Range. As the wildlife conflict management specialist for Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks (FWP) in northwest Montana, Vallieres remembers it as one of countless instances she wishes she could have been in two places at once.

Lacking that superpower, the bear biologist hopped into her government pickup truck and drove two hours over the mountain pass to the site of the train strike, where she found a dead 25-year-old male grizzly and set to work documenting the federally protected bear’s death.

“We get stretched thin,” Vallieres said. “Up here in northwest Montana, we have the highest density of bear-human conflicts in the state, and we’re putting in 60- to 80-hour work weeks responding to them. So yeah, having to go investigate a grizzly bear killed on the train tracks adds to the burden and distracts us from our efforts to keep bears and humans safe.”

Ten days earlier, on Sept. 8, Vallieres was wrapping up her workday around dark when she received a mortality signal from a 10-year-old radio-collared sow grizzly whose coordinates help wildlife officials monitor population trends. Its location? A BNSF Railway Company trestle spanning the Flathead River near Coram.

“When I saw that the mortality sensor was near the train tracks, I knew I had to get there as soon as possible,” Vallieres said. “We’ve had a few on that train trestle in Coram. It’s so high up that they either try to jump off or outrun the train. And they can’t outrun the train. It would be nice if BNSF would install some motion-sensor alarms across the trestles to scare the bears so they won’t keep trying to cross them.”

For decades, the freight trains trundling over Marias Pass toward Glacier National Park and the Great Bear Wilderness along a 206-mile stretch of tracks between Shelby and Trego have posed a threat to the grizzlies living there, particularly when a derailment causes a grain spill, or a train-killed deer or livestock carcass draws the bears onto the busy tracks. And for decades, a host of state, federal and tribal wildlife management agencies, as well as non-governmental organizations and conservation groups, have worked with the railroad to mitigate the hazards to threatened and endangered species like grizzlies, with varying degrees of effectiveness.

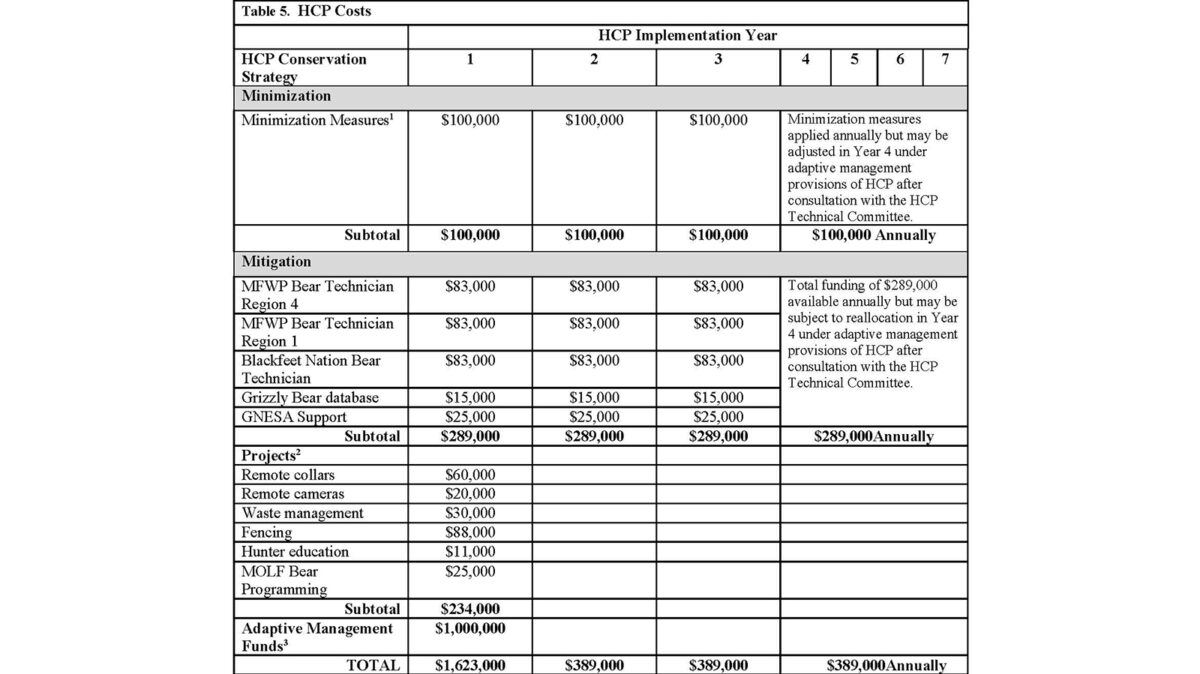

Three years ago, BNSF Railway Company proposed the most comprehensive solution yet when it applied to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for an Incidental Take Permit (ITP) and formally submitted a Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP) outlining measures it would take to reduce train-caused grizzly mortalities in the region. The HCP committed more than $2 million to fund the salaries and operational costs of two new FWP grizzly bear technicians and a third grizzly bear technician for the Blackfeet Nation, as well as related grizzly bear conservation projects and programs, including waste management, electric fencing, remote cameras, radio collars, hunter education, and a new grizzly bear database over the seven-year life of the plan.

Under the plan, BNSF would also establish a reserve account of $1 million to fund programs and projects designed by the HCP technical committee to respond to new data discoveries, the identification of new factors contributing to train strikes, “or the arrival of new challenges and solutions as grizzly bear populations expand.” Developed over the course of nearly 20 years and based on extensive consultation with bear experts from U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), FWP, the Blackfeet Nation, and Glacier National Park, the plan and the pot of BNSF money would be administered by the Montana Outdoor Legacy Foundation, a nonprofit organization that works closely with FWP on conservation efforts throughout the state.

In exchange, FWS would issue BNSF an ITP under Section 10 of the Endangered Species Act (ESA), an exception that allows the federal wildlife management agency to issue permits for the “incidental take” of grizzly bears “if such taking is incidental to, and not the purpose of, the carrying out of an otherwise lawful activity.”

However, with the recent spate of train-killed grizzlies in September, including a third grizzly mortality last month on BNSF tracks east of the Continental Divide on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation near Meriwether, many of the same bear specialists who helped develop the HCP — and who are poised to benefit from its finalization — are confounded by the postponement of both the plan and the incidental take permit, which is a legal requirement under the ESA.

“I don’t understand what the holdup is,” Gerald “Buzz” Cobell, director of the Blackfeet Fish and Wildlife Department, said. “I think BNSF is dragging its feet and the Fish and Wildlife Service is letting them do it. The tribe is anxiously awaiting this funding to make up for some of the grizzly bear losses that are occurring on the railroad tracks running through the reservation. As a tribe, we’re doing our best to minimize grizzly bear mortality and our feet are held to the fire whenever there’s a death. But I guess if you’re BNSF you get a free pass.”

Trains hitting bears has long been a problem in northwest Montana, particularly in the 1980s and early 1990s, when a series of derailments left spilled grain along the right-of-way that attracted bears. In the 1990s, BNSF Railway predecessor Burlington Northern teamed up with FWP, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the National Park Service and other stakeholders to create the Great Northern Environmental Stewardship Area in an effort to reduce the number of train-related fatalities. The railroad increased its efforts to pick up spilled grain and to reduce vegetation along the tracks that might attract the animals.

According to data tracking bear deaths from 1980-2018, trains along BNSF Railway corridors killed or contributed to the deaths of approximately 52 grizzly bears from the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem (NCDE). In 2019, eight grizzly bears were killed as the result of railway activities, the most in a single year on record, while dozens more were removed from the recovering population through management actions, the result of bears killing livestock or getting into human food.

Following the train-related deaths in 2019, wildlife advocacy groups threatened to sue BNSF Railway for its role in train collisions killing grizzly bears. The following year, BNSF submitted its draft plan to FWS, which in February 2021 posted the 60-page HCP for public comment.

Since then, both BNSF and FWS have offered scant details about the plan’s progress.

“BNSF is working with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to finalize its Habitat Conservation Plan,” according to a Sept. 22 email from Lena Kent, general director of public affairs for BNSF. “In the interim, BNSF continues to work with the federal, state and Tribal agencies in reporting and facilitating the investigation of potential bear strikes on the railroad right of way. BNSF also continues to work to identify and remove potential bear attractants from its track structure. This includes vegetation management, carrion removal, and identification and removal of spilled agricultural products.”

The Beacon asked BNSF to clarify the reason for the delays that have stalled the HCP and the company’s application for an Incidental Take Permit, but the company did not respond.

Thomas Stoever, an attorney who represented BNSF and helped author the HCP, said he couldn’t comment on the procedural delays and directed the Beacon toward BNSF or FWS.

On Sept. 21, the Beacon sent FWS a formal request for comment on the progress of the HCP. As of Oct. 4, Joe Szuszwalak, acting deputy assistant regional director for the agency’s office of communications, said he still had not received clearance for a response.

By most accounts, BNSF’s efforts to clean up bear attractants from its railway have been exemplary, as has the response by BNSF employees when a train strike does occur.

“I will give BNSF some recognition there,” said Tim Manley, a retired grizzly bear biologist who spent 37 years as FWP’s grizzly bear management specialist in northwest Montana. “They did make some changes over the years and the local railroad folks were excellent to deal with. When bears did get hit, we would go investigate and try to make sure we could identify the attractant, get it cleaned up, and get electric fencing around the grain spills.”

When Manley was hired in 1993, his position was funded by BNSF, which back then faced the same legal mandate to mitigate grizzly bear mortality that it does now. In 2004, he served on the technical committee assembled to inform the development of the railroad company’s HCP.

Today, Manley is at a loss to explain why the conservation plan hasn’t been finalized, although he speculates it has something to do with the likelihood that grizzly bears in the NCDE will soon be proposed for delisting.

“I have essentially been involved in this thing for 20 years and my opinion is that BNSF is stalling until bears get delisted, in which case they wouldn’t need an incidental take permit,” Manley said. “In 2021, the final draft was put together and sent out for public comment. It still has not been signed off on by BNSF and here we’re going on three years.”

Under the draft plan and application for a seven-year take permit, BNSF acknowledged that grizzlies in the NCDE would soon be delisted and considered that probability as part of its application.

“BNSF expects that within seven years, the NCDE population of grizzly bears will be delisted and the post-delisting monitoring period of the population will be complete,” the draft plan and permit application states. “At that time, it is anticipated that the NCDE grizzly bears population will continue to be managed through a conservation strategy implemented through Federal, Tribal, State, and local stakeholders in the region (NCDE Subcommittee 2019). At the end of the Permit duration, BNSF may voluntarily continue its HCP conservation strategy. If the NCDE population is not successfully delisted within the seven-year Permit duration, BNSF may apply for a Permit renewal.”

Mitch King, a 31-year FWS employee who now works as executive director of the Montana Outdoor Legacy Foundation, the nonprofit organization that would administer the HCP’s funding under the plan, said that, to the best of his knowledge, BNSF and FWS were still ironing out the details.

“This thing has sort of been hanging around for decades now,” King said. “It just seems to drag on and on. Meanwhile, the trains have taken a toll because they’re operating in prime griz habitat. You can’t stop those trains on a dime, so there’s no way they’re ever going to make them completely bear proof.”

Hence, the need for a take permit.

Chris Servheen, who for 35 years worked as the FWS’ grizzly bear recovery coordinator before retiring in 2016, said he can’t understand why the draft HCP hasn’t been formalized, particularly since BNSF stands to benefit from a relatively small investment in grizzly bear conservation.

“It’s pretty embarrassing for a multibillion-dollar company to try and save a few nickels on the backs of grizzly bears,” Servheen said. “This plan has been ready to go for years and it’s all been examined in great detail and it lays out what they can do to help offset some of the effects of the railroad by helping fund some of these positions. It’s not a huge financial imposition on them so I can’t understand why they’re trying to avoid responsibility.”

For Vallieres, the HCP’s inclusion of funding for another FWP bear technician holds special meaning — when Manley hired her as a seasonal technician, it was understood that in order for her to join FWP as a full-time employee, the HCP would need to be finalized. Instead, she assumed Manley’s role when he retired.

“When I started working for Tim, he always had to raise money for his tech positions,” Vallieres said. “I just remember him telling me that my job would be funded once they pass the HCP, which had been in the works for a long time. It just never happened. It still hasn’t happened.”

Even in retirement, Manley keeps tabs on bear management and conservation in the region and beyond. But as more biologists retire, he says the endangered grizzly bear is losing some of its most dedicated champions.

“Pretty much all of us who served on the original HCP technical committee are retired now,” Manley said. “I have asked repeatedly through the years what the status is of the HCP and I was told it was being passed back and forth between BNSF and [FWS]. At this point, I don’t know where things stand. It’s basically in BNSF’s hands.”