Tracking Montana’s Raptors

Every fall, biologists and avid birders clock hundreds of hours on nearby mountaintops to count migrating birds of prey, part of a global network of sites collecting raptor population data to help identify threats to species and aid conservation

It first appeared as a speck in the distance, barely visible through a pair of binoculars.

“Right there, left of that notch in the mountains like a gunsight,” said BJ Worth, pointing towards a distant peak.

The raptor came in low and swift, soaring along the crest of the Swan Mountains like a feathered B-52. In mere minutes it had covered miles of distance in the approach toward Mount Aeneas, vast wings lifted in a slight “V,” wingtip feathers spread out like fingers seven feet apart.

Worth swung his camera around, telephoto lens tracking the massive bird as it passed within a few dozen feet of him.

“Adult golden eagle, how cool,” Worth said as the raptor glided off to the south. “So, that’s our first bird of the day. I’ll bet this could be a 100-bird day.”

Worth pulled out his smartphone and logged the sighting on a tracking app.

At eight other experimental and established sites in Montana, scientists, avid birders and volunteers were marking similar observations, part of a global network of locations collecting data on migrating raptors during September and October. The network is organized by Hawk Watch International (HWI), a nonprofit founded by Steve Hoffman in the 1980s as one of the first efforts to understand raptor migration patterns and population trends, in cooperation with regional Audubon Society chapters and government agencies.

The Montana Hawk Watch sites, and others throughout North America, track raptors — hawks, eagles and falcons — along various aerial corridors, which Worth describes like a massive river network.

“There’s about 150 sites like this around the United States and Canada, and we’re situated on a tributary here on the edge of Jewel Basin,” Worth said. “There’s another corridor on the next ridgeline over, and the one beyond that. I think a lot of the tributaries that come through these ridges all converge somewhere around where 200 meets 83, and then join into bigger and bigger rivers of raptors. By the time you get down to Texas, there’s massive groups of them circling on the thermals of hot air — you can get groups of raptors, called kettles, with tens of thousands of birds.”

Up in Montana, along the narrower tributaries of the continental flyway, most of the migrating raptors show up as solitary travelers, but on busy days can pass by with startling regularity.

In the hour following the golden eagle’s flyby, Worth spotted a cooper’s hawk, two northern harriers, six sharp-shinned hawks “sharpies,” and an American kestrel.

Worth has been an observer at the Jewel Basin Hawk Watch site since it was established in 2008 by Dan Casey of the Flathead Audubon Society. The Audubon provides funding for the site, which is run by Josh Covill and manned by numerous volunteers over the fall. Observers will usually put in eight hours of counting time during a day with good weather.

The best weather for the Jewel Basin site is a clear day with winds blowing from the southwest, according to Worth. When the winds push up against the ridges along the Swan Range it creates an updraft and the birds can fly south along that bubble of air along the top of the ridge with minimal effort — much like a sailboat tacking at 45 degrees into the wind.

Often the raptors glided by far overhead riding the air currents, oblivious to the spotters below, but the lower flying birds will sometimes glimpse a great-horned owl decoy that is set up a little way down the ridgeline. Owls are natural enemies of most raptors, due to a propensity for robbing nests for chicks, so even juvenile raptors will exhibit aggressive behavior towards an owl. When the decoy catches the eye of a passing bird, they’ll often pivot in mid-air and dive down to attack, offering Worth or another observer the chance to see them up close.

“When they come within 20 yards or so, we get a better opportunity to get an identification on them,” Worth said. “It also puts a smile on my face watching raptors that close.”

The kestrel did just that, changing direction with a flap of its wings and shooting towards the owl, a colorful blur of blue and red. A loud cry of klee klee klee klee klee klee split the air as the angry kestrel swooped in and around the decoy, before finally deciding it wasn’t a threat and winging off.

“Did you hear that? Just fabulous. The falcons tend to talk more than the other birds, and that kestrel was just doing its thing,” Worth said beaming. “I think I’ve only heard that up here a once or twice over the years.”

Each hawk watch site tracks a different breakdown of raptors due to their location along the migratory tributaries.

At Jewel Basin, more than half of all raptors spotted are sharp-shinned hawks. As of Oct. 17, 1,492 “sharpies” had been seen winging along the Swan Crest. Golden eagles, on the other hand, are more of a luxury here, making up just five percent of sightings.

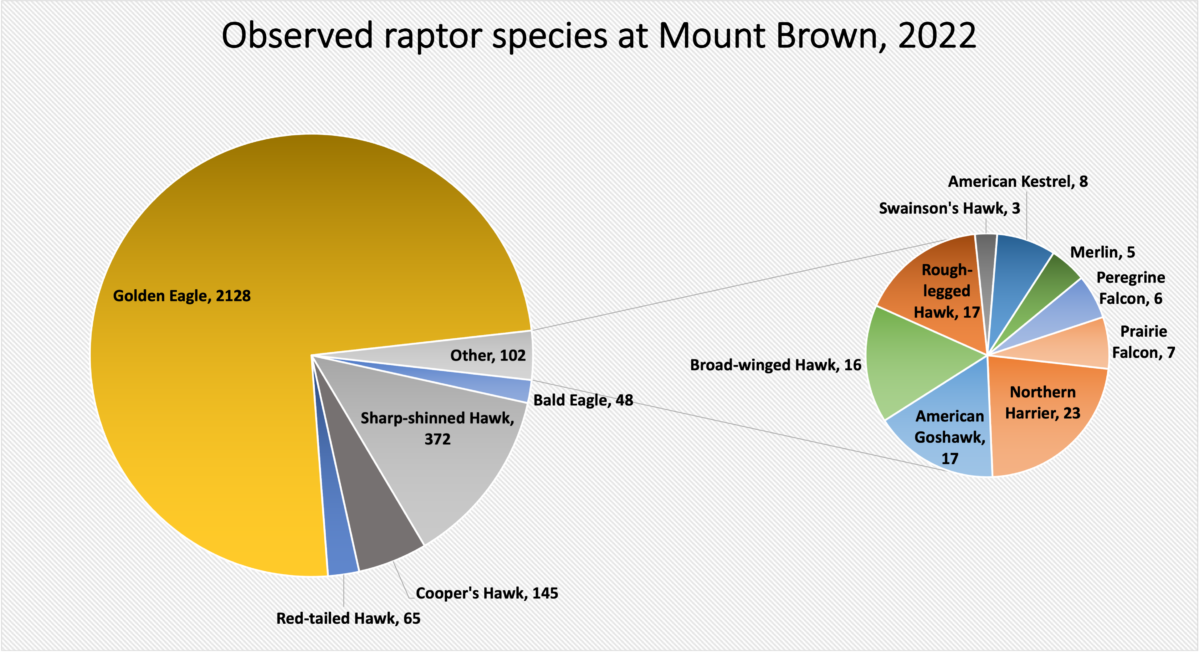

Thirty miles to the northwest, however, the golden eagle is the primary focus for biologists in Glacier National Park (GNP). On Oct. 8, observers spotted 160 golden eagles passing below Mount Brown, where an official hawk watch site has been set up since 2018.

“Most people who come to Glacier are totally into the grizzly bear because it’s the top predator in the terrestrial ecosystem,” GNP wildlife biologist Lisa Bate said, pointing towards an eagle flying over Lake McDonald. “But that is also the top predator in terrestrial ecosystems, just in the air. I mean, seriously, that’s the same niche that it fills. And so for any raptor, they’re great indicator of the overall health of our ecosystems.”

In the mid-1990s, biologists identified Glacier Park as an important migration corridor for golden eagles and recorded around 2,000 eagles annually migrating past Mount Brown from 1994 to 1996.

Since then, trend data from regional hawk watch sites, including in the Bridger Mountains, indicated a decline in population for the eagles that biologists attribute to habitat loss, environmental contaminants and climate change. Bate, along with GNP citizen science coordinator Jami Belt, decided they were well positioned to replicate the studies from the 1990s and add their own data to try and understand the species’ decline.

Unlike the older studies, which were conducted from Lake McDonald Lodge, Bate and Belt decided to find a location higher up in the mountains to make spotting and identifying birds easier.

After five years of gathering preliminary data at locations scattered around the park, they established an official hawk watch site on Mount Brown, 25 switchbacks up the trail that accesses the mountain’s lookout tower. Funding from the Northwest Montana Lookout Association was used to help restore the Mount Brown lookout, which is used by park staff to store equipment and spend the night, negating the need to hike up and down the mountain during counting season. The location also best correlates with the older data from Lake McDonald.

“When you see a raptor close up, it’s just that thrill of excitement,” Bate said. “I mean, a lot of times you’re looking these raptors in the eyes, they’re so close.”

The proximity of the eagles, which often soar within 100 feet of the trail, along with the popularity of the lookout as a hike for visitors offers an opportunity to educate the public.

Each October, the park hosts a Hawk Watch Day at Lake McDonald, where biologists and park staff give presentations on how to identify and count migrating raptors, the integral role they play in our ecosystems and the risks they face.

Two of the biggest threats posed to eagles in Montana is lead poisoning, which the birds ingest while scavenging animals hunted with lead ammunition, and poisons used to kill rodents. There are also threats from powerlines, wind turbines and invasive plants, which can impact prey animals the eagles rely on.

“Most visitors to the park aren’t even aware that we have golden eagles because most people don’t look up,” Bate said, adding that on the busiest days it’s not unusual to see several hundred eagles pass by Mount Brown. “And that’s why it’s important to get people up to places like this on days when we’re counting dozens and dozens of eagles. There’s nothing quite like it.”

While golden eagle observations are currently down this year compared to the previous two, the overall data from Mount Brown is not yet clear on whether the eagle population is still declining or holding steady, according to Bate, as it takes roughly 10 years of data to establish clear trends, but another project within the park has offered more concrete clues.

In the 1990s, biologists had records of 49 active nesting sites within the park, but by 2020 Bate knew of none. For the last three years, Bate and Belt have recruited groups of citizen scientists to search for nests, which are often high on mountainside cliffs. In 2021, a single nest was located, but this year they found seven. Worth was recruited to the project this year, spending days photographing and filming golden eagle chicks.

“It’s amazing to watch these birds slowly grow and fledge over months,” Worth said. “Then suddenly they’ll go from not being able to leave the nest to joining the migration the next day.

The more data obtained by biologists and citizen scientists alike, the more likely researchers will be able to identify and mitigate threats to the species.

“We’re really trying to get a pulse on what this all means,” Belt said. “These birds are really challenging to monitor but knowing what they’re doing from year to year is really valuable for not only helping understand what’s going on within the protected landscape of the park, but what threats are outside of its boundaries.”

“If we don’t take part in this work and collect this data and educate the public on what’s going on, we might suddenly realize there aren’t enough eagles around for the species to persist,” she continued. “And it would be hard to know that until it’s too late to do anything about that.”