New Study Details Shrinking, Vanishing Glaciers Across Lower 48

A new comprehensive inventory of glaciers in the Western U.S. shows fewer and smaller icy features than previously detailed, including six lost from Montana

Six named snow features in Montana no longer meet the standard definition of a glacier, removing them from the official inventory of glaciers in the state, according to a new study published in Earth System Science Data.

The study, authored by Portland State University geology professor Andrew Fountain, was the first comprehensive inventory of glaciers and perennial snowfields in the Western U.S. compiled since the 1960s and provides a new baseline for assessing glacial changes in the future.

“Glaciers only go in one direction — they go downhill, and they shrink,” Fountain said. “We all know that glaciers have changed a lot in the last decades, so we were motivated to figure out what the extent of that change was.”

About a decade ago, Fountain had a realization while looking at the standard USGS topographic maps. The maps depict named glaciers — one of the only comprehensive mapping of glaciers done in the U.S. — but the data was outdated.

“Some of those maps, at least for Montana, date back to the 1960s,” Fountain said. “If you look at them, they’re updated every few decades, but they don’t update the glaciers, just the human infrastructure.”

Cross-referencing old maps, lists of named glaciers and utilizing satellite imagery from 2013-2020, Fountain and his co-researcher Bryce Glenn spent more than a year mapping and digitizing the extent of snowfields and glaciers throughout the country. While using satellite imagery is easier than surveying glaciers in the field by hand, there were still some obstacles — imagery had to be taken during summer months without additional snow cover, and determining whether a snow field is moving, a defining feature of a glacier, is difficult from a photo. The key to the latter, Fountain said, is identifying crevasses, the large cracks that open up when a glacier is moving downhill.

Fountain received funding for the project from the U.S. Forest Service (“They own most of the glaciers anyway,” Fountain said), which came through just before the COVID-19 pandemic swept across the globe.

“It was a really great COVID project. We could just sit at home, traveling around the western U.S. through aerial photos of this fabulous terrain — especially in Montana — and outlining the glaciers as we went,” Fountain said. “It was very meditative.”

Even though the new inventory is the most accurate, comprehensive survey of the nation’s contiguous states’ glaciers, Fountain acknowledged there are limitations to the method they employed.

“The ideal way to conduct a survey is through field work, but there’s a limited season to survey a glacier or snow field, no one has the manpower or funding for it and many of them are difficult to reach by foot,” he said. “You can’t survey the lower 48 by walking to them.”

Over the course of 18 months, Fountain and Glenn, outlined and digitized a total of 2,542 features, including 1,331 glaciers and 1,176 perennial snowfields.

The standard definition of a glacier is a perennial snowfield that moves on its own and is at least .1-kilometer squared — roughly the size of two football fields side by side.

Under that definition, Fountain found that 52 of the 612 officially named glaciers in the country no longer exist, either because they are now too small to qualify, or have completely disappeared.

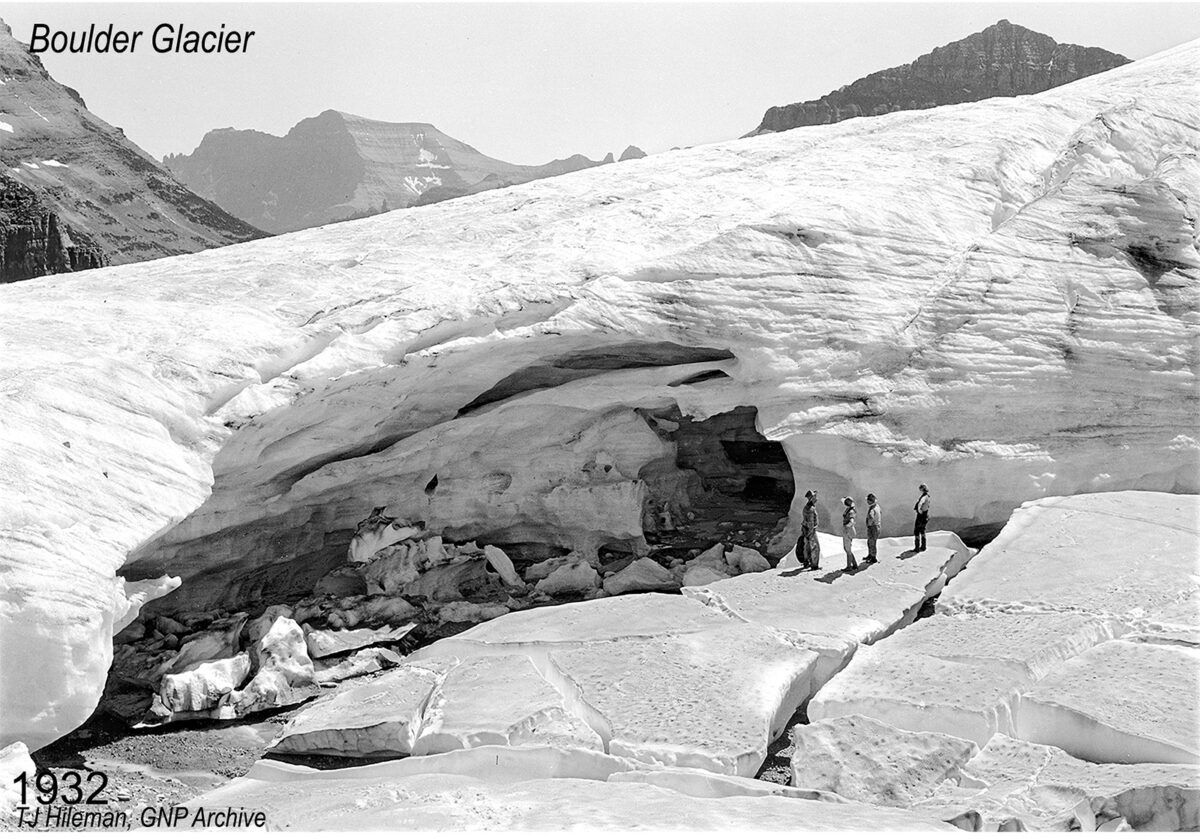

In Montana, there are six named features that no longer qualify as glaciers since the last regional inventory. The Grasshopper Glaciers (one in the Beartooth Mountains and one in the Crazy Mountains) are now considered rock glaciers, a mixture of rock and ice. The Blackwell Glacier in the Cabinet Mountains, the Boulder Glacier in Glacier National Park and the Gray Wolf Glacier in the Mission Mountains are all classified as perennial snowfields that no longer move under their own force. The Fissure Glacier in the Missions measured too small to be classified as a glacier.

On the other side, however, Fountain was surprised that several small glaciers in other parts of the state newly qualified for the inventory.

According to the inventory, Montana has 210 glaciers, the majority of which (145) reside in the eponymous national park. Eleven glaciers were mapped in the Mission-Swan-Flathead ranges, 50 in the Beartooth-Absaroka ranges, three in the Crazies, and one in the Bitterroot Range.

“Look at the Crazy Mountains, they still have glaciers there. They’re small, but they’re there and as a glacier fan I think that’s terrific,” he said.

Two things jumped out at Fountain from the collected data. The first was the number of glaciers that had disappeared completely.

“Glaciers are tough to erase. What happens is they retreat into better and better environmental niches, like shadowed headwalls where they can get extra snow through avalanches. A little glacier in a shadow that regularly gets an avalanche dumping snow on it, it can almost become climate insensitive in a way,” he said.

Fountain was also intrigued by the way he observed glaciers were shrinking. In the traditional model of glacial retreat, the front of a glacier will gradually recede uphill, but Fountain found several examples of glaciers effectively melting directly into the landscape.

“When we mapped out some of the glaciers it was hard to tell whether there was ice between rocks, or rocks sitting on top of ice. The lines are more blurred,” Fountain said. “It’s an interesting form of how they’re disappearing.”

Even though his work is essential to the field, Fountain said studying and observing something that is actively vanishing can create something of an emotional rollercoaster.

“One day not too long ago it emotionally dawned on me that maybe in 50 to 70 years from now, nobody will read my work, because there won’t be anything to read about. It’s like doing all this work on the dodo bird, and now it’s gone,” Fountain said. “It almost feels like I’ve wasted my time, but then again, who reads any studies that are 70 or 80 years old?”

On the other hand, Fountain revels in the continued awe he feels when he visits the icy landforms in person.

“Sometimes doing work digitally, without going in the field can make you lose touch with what these features really are. But standing on a glacier, it’s just an unbelievable feeling,” he said. “You get this feeling in the middle of the summer when you’re on top of this giant piece of ice, where it doesn’t make sense that it exists. I’m always taken by the incredible beauty of these features.”