Remembering the Tragedy on Peters Ridge

Thirty years after an avalanche killed five people in the northern Swan Range on New Year’s Eve, local rescuers, skiers and snowmobilers reflect on the tragic event and the evolution of search and rescue protocol and avalanche education that followed

By Maggie Dresser

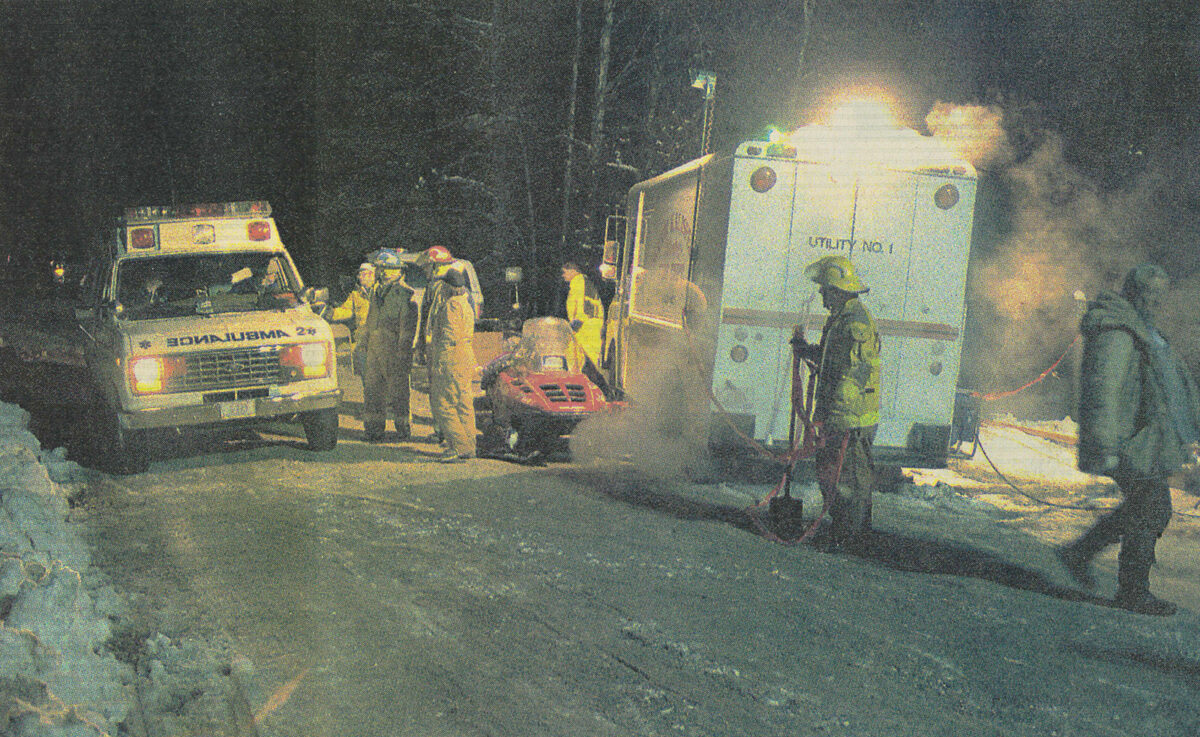

Thirty years ago on New Year’s Eve, 38-year-old Steve Burglund arrived at the accident site in the Swan Mountain Range northeast of Bigfork to find uniformed firemen, sheriff’s deputies, search and rescue (SAR) personnel and dozens of first responders and volunteers. Snowmobiles were zooming in and out of the forest two miles away from the nearest road, hauling rescuers and gear, while authorities relayed information to the 911 dispatcher.

Just after noon on Friday, Dec. 31, 1993, a report of an avalanche near Peters Ridge north of Strawberry Lake involving separate parties of 14 snowmobilers had been called into the Flathead County Sheriff’s Office (FCSO) dispatch center. Six of the snowmobilers were missing, including a 7-year-old boy.

As a member of the Flathead Nordic Ski Patrol, a nonprofit organization of volunteers trained to respond to backcountry emergencies, Burglund was appointed as the accident site manager shortly after arriving to the scene. Among a sea of emergency responders, he was deemed the most qualified rescuer to initiate a search amid the hazardous avalanche conditions where “hang fire” – a term to describe unstable and potentially hazardous snow that lingers above an avalanche crown – still existed.

“Everyone wanted to help,” Burglund said. “These volunteer firemen and QRU [quick-response unit] members are all trained to help, but this incident was so different – it was so remote.”

Rescuers with avalanche transceivers switched the devices to search mode, but they failed to pick up any signals. A hasty party ensued and Burglund initiated a probe line – a last resort effort locating buried avalanche victims that entails a row of people systematically probing the snow in hopes of locating a body with a “strike.”

An hour after the avalanche, one of the missing snowmobilers, Jamie Merrill, a Canadian man in his 40s, was recovered. He was hypothermic, but alive and unscathed after he was buried almost six feet deep next to his snowmobile, which officials say likely provided him with an air pocket that saved his life. His 7-year-old son, Miles, was still missing.

The four remaining adults were found by 4 p.m., according to an incident report completed by Stan Bones, a forecaster with the Northwestern Montana Avalanche Information System who helped with the rescue and investigated the incident. Each were buried about five feet deep, and while responders attempted CPR when they were found, none of them could be resuscitated.

Burglund remembers when a responder on the probe line hit a positive strike on his friend, Pat Buls, a 46-year-old Kalispell firefighter. When they excavated his body with shovels, the snow was caked into Buls’ nostrils and his helmet, forming what Burglund describes as an ice mask that blocked any oxygen from entering his friend’s airway.

After someone relayed the discovery to dispatch, Buls’ body was placed into a toboggan, covered up and transported to a staging area for the victims.

“Everyone just stopped and watched,” Burglund said. “You took it all in.”

But as the sun set on New Year’s Eve, rescuers still could not find Miles. Soon after dark, the responders set up a light generator to illuminate the scene. There were 75 people at the incident site, two probe lines, and two Canadian avalanche dogs searching the runout zone beneath the slide.

Meanwhile, increased snowmobile traffic continued moving in and out of the area as the night went on and personnel had to navigate a steep hill that required a pully system to move machines in and out of the site.

Exhausted responders continued searching past midnight and into New Year’s Day, but by 2 a.m., officials suspended the mission until the next morning.

“To leave that scene that night was traumatic,” Burglund said. “(Miles’) father was so devastated.”

Burglund went home that night and did not return to Peters Ridge the next day.

“That day seems like a dream to me,” Burglund said.

When 30-year-old Jim Bob Pierce and his friend Larry Brazda led a party of 10 other snowmobilers, most who were visiting from Alberta, to ride at one of their favorite spots near Peters Ridge in the Swan Range, it had just snowed 3 feet following a December dry spell.

The snow continued to fall when they arrived at the trailhead where they ran into local riders Rickey Anderson and Pat Buls, who joined their crew. The group of 14 people took turns breaking trail as they rode to the Swan Crest.

The crew took turns sledding up to the notch past the Krause drainage, but they struggled to ride up the last steep pitch through the deep powder. Tired from the failed attempts, Pierce turned his sled around to head back down to the bottom for a lap before returning to the top to try again.

When he reached the bottom, he turned his sled’s engine off and, to his surprise, six people were right behind him.

“Right then, there was a big blast of air and snow and debris flying from behind us,” Pierce said. “I said ‘Avalanche!’ and tried to fire my sled up but I had the kill switch on at the time.”

By the time Pierce finally switched his machine back on, the snow had settled. He rode through the avalanche debris to the same spot he had just left his friends, but he found only Sandy Sherman buried to her waist.

“I said, ‘Where is everybody?’ And she said, ‘I don’t know. They were all just here,’” Pierce said. “That was a really terrible feeling.”

Pierce, who describes himself as a “techy” guy, had a cell phone in the early 90s and dialed 911. He rode back to his six friends and told them everybody was gone. They dug Sandy out of the snow and started looking for the six missing people, using branches as makeshift probes.

According to Bones’ incident report, Brazda saw the bottom of a Polaris snowmobile ski as he rode to the top of the debris. He dug into the snow with his gloved hands, but his efforts proved to be futile.

“It was the most helpless feeling I’ve ever had,” Pierce said.

The Flathead County Sheriff’s Office (FCSO) dispatcher logged the call at 12:52 p.m. that day, and quickly alerted authorities. According to Bones’ report, the East Valley Quick Response Unit, the Creston Volunteer Fire Department and ALERT air ambulance were dispatched. Flathead County Search and Rescue, Flathead Nordic Ski Patrol and the Kalispell Police Department also responded to the scene along with dozens of volunteers.

Shortly after the members of the snowmobile party realized they needed equipment and personnel to find their friends, they rode down to the trailhead to wait for rescuers.

“What was so amazing – and I’ll never forget it – I was halfway out of the trail, and we were already meeting snowmobiles and people coming to help,” Pierce said.

Chuck Curry, the Flathead County undersheriff at the time, remembers when the call came in. He was off duty that day, but he and a deputy headed to the sheriff’s office, loaded up two snowmobiles and drove to the trailhead. The law enforcement officers arrived at the scene following challenging riding conditions and began handling logistics.

As the undersheriff, Curry had been on a wide range of accidents before, including a few avalanches, but he said Peters Ridge was different.

“Obviously we had had avalanches before, but never one that extensive with that many victims in that remote of a location, on New Year’s Eve,” Curry said.

By 7 p.m., Pierce finally left the avalanche site and rode to the trailhead to rendezvous with his wife, Serena, and waited there until about midnight.

“We were just exhausted and didn’t know what else to do,” Pierce said. “We just couldn’t find Miles.”

On New Year’s Day, 1994, the search resumed with a fresh search team of about 27 people, according to the incident report. Two Canadian avalanche dogs with handlers along with volunteers from multiple SAR agencies and Flathead National Forest officials responded.

Five inches of new snow had fallen the night before and during the search, the snowfall was measured to be more than an inch per hour, adding to the avalanche hazard for the search party.

Since so many people had been at the scene, the search zone had been “contaminated,” which created a challenging environment for the search dogs to get any finds. A Canadian black Labrador named Jess continued returning to an area where there had previously been unsuccessful probe strikes.

But a digger was assigned to that spot anyway, and Miles was found 10 feet beneath the snow’s surface, just deep enough that the 10-foot probe couldn’t reach him.

Miles’ body was recovered 10 minutes before the search was planned to be suspended as the storm intensified, and 24 hours after the avalanche occurred.

Bones was waiting at the road on the second day where the ambulance was staged. He remembers watching Merrill carrying his son down from the accident site and placing his body in the ambulance.

“I don’t think there was anyone up there that wasn’t overcome by it,” Bones said.

For days and weeks following the avalanche, newspaper headlines read, “Snowmobilers Ill-prepared for Killer Avalanche” and “New Year’s Tragedy,” serving as a harsh reminder to the survivors. Pierce remembers getting requests from NBC in New York to share his account of what happened.

Meanwhile, Pierce traveled to Alberta to attend the funerals and grieve the losses of Bart Nelson, Kendall Smith, Gordon Sherman and Miles Merrill, whose ages ranged from 7 to 47.

“There were four funerals in the blink of an eye,” Pierce said.

While he remembers the avalanche scene vividly 30 years later, from details like an isolated tree poking out of the avalanche debris to the moment he hopped back on his sled after the slide, he didn’t remember that it happened on New Year’s Eve.

Pierce didn’t fire up his snowmobile right away following the accident, but he did continue riding hard until 2007 – the year after he bought his first helicopter.

Thirteen years after the accident on Peters Ridge, Pierce began donating his time, helicopter and fuel to assist on SAR missions, sparking a decades-long passion.

“I just have a passion for search and rescue,” Pierce said. “That could be because I’ve got good empathy for it through this situation.”

That passion led Pierce to pitch the idea of a formal rescue helicopter operation based in the Flathead Valley to Whitefish philanthropist Mike Goguen.

By 2014, a twin-engine Bell 429 helicopter equipped with a hoist, a camera, a tracking system and cutting-edge SAR technology became operational for missions, and Two Bear Air was officially launched as a partnership with the FCSO as a result of Goguen’s funding. Pierce served as the lead pilot before retiring several years ago.

Since its formation, Two Bear Air has been dispatched to more than 1,000 missions across Montana, Idaho and eastern Washington while adding a half-dozen staff. The organization also continues to advance its technology with specialized equipment like infrared cameras and RECCO SAR detectors — instruments that can be suspended from aircraft to quickly scan vast swaths of open terrain and help locate buried avalanche victims.

Pierce says he has been on close to 30 avalanche-related missions during his time with Two Bear Air, most of which were body recoveries. But there’s one rescue that stands out in his mind and brings his memory back to Peters Ridge.

In January 2016, Pierce flew to the boundary of Lookout Pass Ski Area on the Montana-Idaho border during a snowstorm to a report of an avalanche that left a skier with a broken femur who was bleeding out. Pierce circled the area several times before he could access the zone in the dark and hoist the victim into the helicopter.

“The guy has gone over the top rescuing people,” said Ted Steiner, a longtime avalanche expert in the Flathead Valley. “If he hadn’t flown in there and gotten that particular individual when he did, they wouldn’t be here … He’s done some incredible rescues that he’s very humble about.”

While those that remember the Peters Ridge avalanche and the impact it had on the community, officials say the accident propelled both search and rescue operations and avalanche forecasting and education forward.

“In those days, I didn’t know that much about avalanches,” Curry said. “A lot of us didn’t.”

Curry, who served 34 years with the FCSO, including eight as sheriff before retiring in 2018, now works as a rescue specialist with Two Bear Air.

“I think professionally for us, the biggest thing that happened — and I think probably in the search and rescue community, too — is we spend a lot more time on avalanche education,” Curry said. “We were working in a hazard zone after dark, probably not even realizing the potential risks to the rescuers, especially at a point where it’s no longer a rescue – it’s a recovery.”

At the time of the incident, nobody in the snowmobile party had avalanche rescue gear or education. Pierce said one person in the party wore a transceiver, while a few other riders had left their transceivers in the truck. Nobody was carrying shovels or probes.

“When you’re unprepared and helpless and you’re trying to find people alive and you don’t have the tools to do it – it’s just really tough,” Pierce said.

Before Peters Ridge, Pierce said he had no avalanche awareness, and the threat of a slide didn’t even occur to him.

“We weren’t throwing caution to the wind because we didn’t know that there was caution to be thrown,” Pierce said.

In the early 90s, snowmobile technology was just beginning to advance to the point where sleds could travel deep into the backcountry and access steep avalanche terrain. High-marking – an activity in which a snowmobiler rides as fast and as far up a steep slope as possible before doubling back – was just beginning to gain popularity.

“Technology was advancing faster than the rider’s awareness and the understanding of avalanches,” Bones said. “This was about the beginning of the era of snowmobile avalanche accidents. And to have it be five people – it’s extraordinary.”

Bones, who worked for the Flathead National Forest issuing advisories with the Northwestern Montana Avalanche Information System at the time, wrote in his incident report that the slide failed on a layer of surface hoar, and it broke 2 feet deep and 350 feet wide, running about 800 vertical feet on a west-facing slope. He also wrote that, while any rescue involving six deep burials would be complicated and time-consuming, it may not have changed the outcome if the victims had been wearing transceivers — although it would have considerably shortened the body recovery.

After Peters Ridge, Pierce bought a transceiver, along with two spare devices to loan out to friends. He also purchased a shovel and a probe, and he said local stores couldn’t keep avalanche gear on shelves, in part because the tragedy raised awareness.

When Bones first started teaching avalanche courses in the 80s, he said the user groups were primarily skiers and snowshoers. But after Peters Ridge, he started to see more interest from snowmobilers, with avalanche-education courses eventually splitting into motorized and nonmotorized programs as the demand grew.

As a member of the Flathead Nordic Backcountry Ski Patrol, Ted Steiner was on the search and rescue team that responded to the scene at Peters Ridge, which he said informed his career trajectory as an avalanche safety forecaster; however, Steiner said he would rather be on the prevention side of avalanches.

“Everything we can do preemptively to educate people on avalanche safety is a key component,” Steiner said. “I’d much rather be working on the front-end and doing what we can to educate people in regards to avalanche safety than ever have to be tied up in avalanche rescue.”

Following Peters Ridge, in 2005 Steiner accepted a job as lead forecaster with the BNSF Railway Avalanche Safety Program. He’s also worked with The Patrol Fund, a nonprofit that coordinates avalanche education, and he is the current president of the Friends of the Flathead Avalanche Center, a nonprofit that supports the Flathead Avalanche Center.

Avalanche forecasting, too, has grown dramatically since Bones began issuing advisories with the Northwestern Montana Avalanche Information System in the 1980s. In 1995, two years after the Peters Ridge avalanche, Glacier Country Avalanche Center formed, issued 70-second warnings containing limited safety information broadcast on the radio every Friday morning.

Following a rebrand in 2013, Flathead Avalanche Center (FAC) was born, evolving into a more sophisticated Type 1 center shortly after new leadership took over the organization, producing daily avalanche advisories from December through April. FAC Director Blase Reardon took over in 2020 and the center now collaborates with Glacier National Park and the Flathead National Forest to cover more than 1 million acres in the Flathead, Swan and Whitefish ranges along with areas in the park.

“The avalanche center has done such a great job and they’ve really helped a lot,” Pierce said. “Because, if nothing else, there’s just the thought process of somebody saying ‘Hey – avalanches are dangerous, right?’ If you hear that, you have to make a conscious decision.”

Thirty years later, the Peters Ridge avalanche remains one of the deadliest in Montana’s history. To many locals, it’s also a reminder of an avalanche on Mount Cleveland that killed five young climbers in Glacier Park in December 1969.

“Prior to this one there was Mount Cleveland in 1969 and five climbers were killed,” Bones said. “So here – not that many miles away in 1993 – five snowmobilers are killed. It was significant.”

Other avalanches, too, have left lasting impacts on the community, like a 2008 slide that killed 19-year-old Anthony Kollman and 36-year-old David Gogolak in the sidecountry of Whitefish Mountain Resort, in an area known as Fiberglass Hill. In 2017, 36-year-old Ben Parsons died in an avalanche on Stanton Mountain in Glacier National Park.

The cumulative effect of such tragedies has taken a toll on a prevention expert like Steiner.

“I’ve gotten tied into the avalanche education and teaching avalanche safety on the front-end and I just don’t want to see that ever repeated again,” Steiner said. “It’s something that really affects me more than anything else. I don’t know why.”

Burglund – the accident site manager at the scene 30 years ago – said he, too, hadn’t thought about Peters Ridge in many years. And while he remembers participating in debriefings after the rescue, it remains emotional for him.

“I never thought it would bother me to talk about it to this day,” Burglund said.

According to the incident report, Flathead County Sheriff Jim Dupont held a “debriefing” for all organizations involved in the incident on Jan. 5, 1994, while several “critical stress syndrome” debriefings were held for those in the recovery operation.

Curry – the Flathead County undersheriff at the time of the incident – said debriefings were in their infancy at this time and have since become more structured, with formal training on how to help first responders process trauma.

Pierce, who is now 60, said he didn’t sleep well for a long time following the avalanche due to the anxiety he experienced following the traumatic event. Overall, he said he’s recovered since the accident, and doesn’t suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder or dwell on the past.

Pierce said he hadn’t thought much about Peters Ridge until he was at a search and rescue conference in Sun Valley a few years ago giving a presentation about Two Bear Air when the incident came up.

“A lot of people think that the only victims are the ones that died,” Pierce said. “But in a situation like this, everybody that’s surviving around you – it’s a very traumatic event. And when you’re unprepared and helpless trying to find people alive and not having the tools to do it – it’s just really tough.”