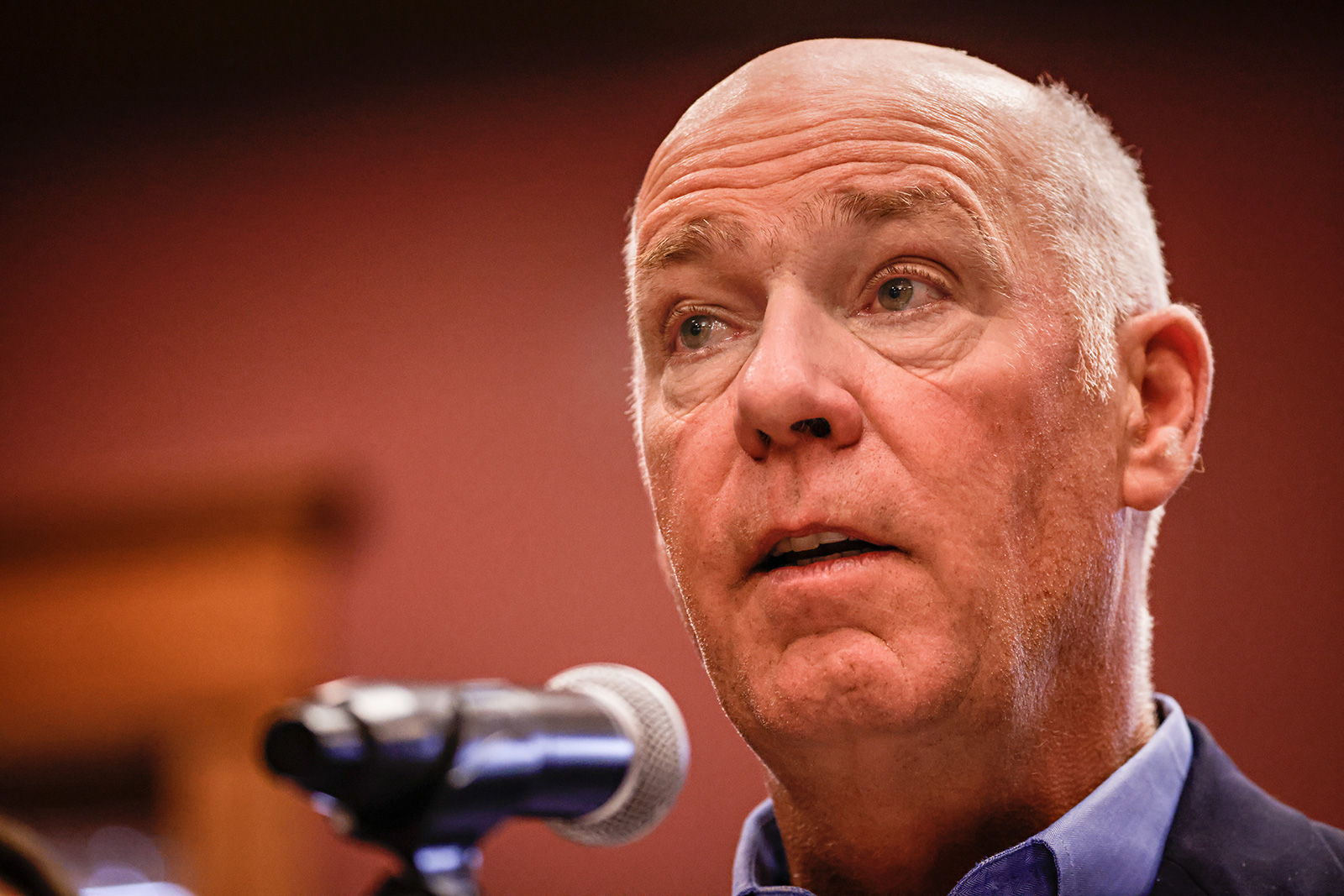

Gianforte Says State Not Responsible for Tribal Law Enforcement in Lake County

County officials frustrated by the decision that means the federal government will likely assume felony law enforcement of tribal members

By Justin Franz, Montana Free Press

Montana Gov. Greg Gianforte has informed the Lake County Commission that the state will not assume felony law enforcement duties on the Flathead Indian Reservation — despite pleas from local officials that they can no longer afford a decades-old arrangement.

The decision likely sets the stage for the federal government to assume responsibility for investigating felony crimes allegedly committed by tribal members within Lake County. It’s unclear how quickly the Bureau of Indian Affairs will be able to establish a law enforcement presence on the reservation.

The letter dated March 1 from the governor’s office broke months of silence after Lake County informed Gianforte in November that its sheriff’s office, county prosecutors and jail system would no longer partake in a one-of-a-kind agreement in Montana under what is called Public Law 280. While officials at both the state and local level — including the tribe, the current sheriff, the county commission and Gianforte himself — have in the past heralded the arrangement as a success, the county says it cannot pay for it any longer.

This week, county officials expressed frustration with Gianforte’s decision.

“None of us wanted out of Public Law 280,” said Commissioner Bill Barron.

Since the 1960s, most law enforcement on the northwest Montana reservation has been handled locally, rather than by federal officers. Lake County’s justice system handles felony crimes, and (since the 1990s) the tribal system handles misdemeanors. Officials, including Lake County Sheriff Don Bell, said the agreement has been successful because things don’t fall through the cracks like they might with federal agents from out of town.

But for the last few years, officials in Lake County have said fulfilling those law enforcement duties has wreaked havoc on its budget. According to the county, the agreement is costing local taxpayers more than $4 million annually. In years past, county officials said the bill was easier to pay thanks to taxes generated by the Séliš Ksanka QÍispé Dam, but once the dam was sold to the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, that revenue dried up.

Over the years, there have been multiple attempts in the Legislature to get the state to help foot the bill. In 2021, one of those passed, but the state only appropriated $1 to the cause. However, that bill did give the county a mechanism to pull out of the agreement — previously only the state or tribe could.

Last year, House Bill 479 would have authorized the state to pay $2.5 million annually for two years to Lake County. But despite passing both chambers, Gianforte vetoed it. In his veto letter, the governor — who in the past has hailed the Public Law 280 agreement as a success — said the county wanted all the benefits of the agreement without having to pay for it. But the county sees it differently, arguing that since the state entered into the agreement with the tribe, it’s the state’s responsibility to cover the costs. The county also took the state to court, but that effort ultimately failed last year.

Late last year, the Lake County Commission voted to pull out of the deal. In November, the board sent Gianforte a letter informing him that the county would no longer provide felony law enforcement on the reservation after May 20, 2024. Gianforte is required by law to make a proclamation releasing the county of its duties within six months. For months, Gianforte did not respond to the repeated letters, except to acknowledge their receipt. In a statement to MTFP, a spokesperson last month wrote the governor’s office was conducting an “internal process and is committed to holding discussions with stakeholders, including Lake County, to identify a path forward,”

But in his letter earlier this month, Gianforte wrote that the plan would not include any money from the state. Referencing the original legislation that established Public Law 280 on the reservation in 1965, the governor noted that there was never a promise of state funding to go along with it and that Lake, Flathead, Missoula and Sanders counties consented to the agreement at the time. (The other three counties also provide felony law enforcement on the reservation. However, the areas where those counties and the reservation intersect are generally small, rural and sparsely populated, and the impact on their bottom lines is marginal.)

Gianforte wrote that the only thing he could do was sign a proclamation that handed off felony enforcement to the federal government, as it is done on other reservations in Montana and around the country.

“I hope you are able to resolve your concerns in coordination with CSKT, the federal government and the counties and cities located within the Flathead Reservation,” Gianforte concluded.

On Thursday, members of the Lake County Commission said that they would meet with the U.S. attorney for Montana in the coming weeks to discuss the next steps. They are not optimistic.

“Our concern is that we just don’t think the federal government or the Bureau of Indian Affairs has the manpower to assume control of this jurisdiction,” said Commissioner Gale Decker.

Decker said that he was “disappointed but not surprised” by Gianforte’s decision. But what frustrated him the most was how long it took for the governor’s office to make its decision. Now the county has less than three months to figure out how felony law enforcement of tribal members will work in its community.

“We really just want a smooth transition,” he said.

As for the tribe, CSKT officials said they were prepared to work with local, state and federal officials to find a path forward.

“Our focus on public safety remains steadfast regardless of the status of PL 280,” CSKT Tribal Council Chairman Michael Dolson said in a press release. “We are committed to security in our communities. As the process unfolds, we continue to prepare and shape jurisdictional considerations for the future.”

This story originally appeared in the Montana Free Press, which can be found online at montanafreepress.org.