FWP Reboots Efforts to Return Native Redband Rainbow Trout to Northwest Montana

In a project that has broad conservation and recreation implications, the state’s only native rainbow trout is poised to make a comeback in the Kootenai River drainage

Committed trout anglers who make a habit of plying the Kootenai River tailwater downstream of Libby Dam, or of plumbing the depths of Lake Koocanusa, may have encountered one of the football-shaped rainbows that grow big and blocky on a steady diet of kokanee salmon, which spill out of Lake Koocanusa like a chum line. The origins of those piscivorous trophy trout, known as Gerrard rainbows, trace back to British Columbia’s Kootenay Lake, and while they’re a hoot to catch, they’re not representative of the northwest Montana fishery’s suite of native species — westslope cutthroat trout, bull trout, and redband rainbow trout.

All three of those species occupy mere fractions of their historic ranges, and have benefited from recent conservation efforts in the Kootenai River system. Lately, though, it’s the redbands, Montana’s only native rainbow trout, that are garnering the attention of biologists working to balance conservation and recreation opportunities in the Kootenai.

Rainbow trout are common throughout much of Montana due to widespread legacy stocking, but almost all of them are nonnatives, descendants of costal rainbow trout originally brought inland from California hatcheries starting as far back as the late 19th century. For years, fisheries managers stocked coastal rainbows in Montana streams containing native redbands, which resulted in the hybridization of two rainbow subspecies, rendering genetically pure redbands increasingly rare.

Today, genetically pure Columbia River interior redband rainbow trout occupy just 15% of their historic range in Montana, all of which is confined to the Kootenai River system; however, as state and federal management agencies increasingly recognize the value of supporting native species on the landscape, particularly in the face of climate change, efforts are underway to restore genetically pure redbands in the Kootenai.

“It’s really a gem of an opportunity to be able to do something that benefits conservation and creates sport fishing opportunities for redbands,” Jim Dunnigan, the Libby Dam mitigation coordinator for Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks (FWP), said. “It’s really special in a place like Montana, where redbands are the only rainbow trout that’s native to the state, and it makes the Kootenai all the more unique. You can go anywhere in Montana and catch a rainbow trout. But where can you go and catch a native rainbow?”

According to biologists, the answer to that hypothetical question could change if conservation measures aren’t taken to support the imperiled redband fishery.

Mike Hensler, the regional fisheries manager for FWP who spent much of his career in Libby, said redband rainbow trout face various threats, including invasive species, habitat loss, and hybridization and competition from introduced fish.

“The long-term persistence of redband trout depends on continued and strategic conservation efforts,” Hensler said.

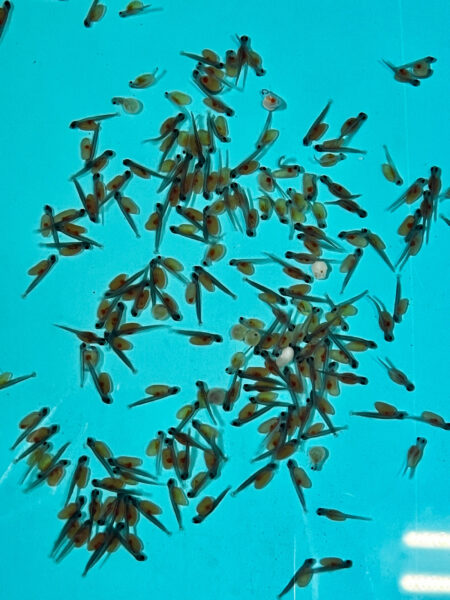

This spring, those conservation efforts began taking shape as part of a program to raise redbands at the Murray Springs State Trout Hatchery near Eureka, where the first embryos hatched the week of June 17. Juvenile fish could be ready to begin stocking in regional lakes by summer 2025.

While inland redband rainbows are found throughout the Columbia River basin, nowhere in Montana has them except the Kootenai River and its tributaries as far upstream as the Fisher River, located a few miles downstream of Libby Dam. Even though it represents the species’ deepest inland penetration, few populations of redbands exist in the U.S. and Canada, and the species is now gone from nearly 80% of its historical range. Due to population declines, redbands are considered a species of special concern by federal and state conservation agencies.

To remedy that, FWP is creating a redband broodstock using native genetic strains of fish that have survived and persisted in isolated streams in the Kootenai basin. The goal of this renewed effort is to conserve wild populations of redbands and the recreational fishing opportunities they provide. Once the brood stock is fully developed, FWP plans to stock approximately 25,000 or more fish annually.

“They are a beautiful fish,” said Brian Stephens, FWP’s fisheries manager for the Libby area. “They have dark-red bands down their sides and anglers love them; they’re a strong, fighting fish that are very catchable. They can get up to 20 inches. But this project has a dual objective: create recreation opportunities for anglers and try to restore redband rainbows to their native range.”

FWP previously raised redbands at its Murray Springs hatchery from 2009 until 2013, as well as the large, lake-dwelling Gerrard rainbow trout. However, operations at the Murray Springs were disrupted in 2013 and the redband program discontinued after a power outage shut down the water pumps at the facility, which is supported entirely by pumped water. According to FWP, about 160,000 fish were lost, including: 30,000 yearling Gerrard rainbow trout that were destined for Lake Koocanusa; 47,000 young-of-the-year redband rainbow trout headed for lakes in the Eureka and Libby area; 2-year-old future redband brood fish that impacted the following year’s redband spawn; 6,000 2-year-old westslope cutthroat trout destined for Holland and Lindbergh lakes; and about 50,000 young-of-the-year Eagle Lake rainbow trout.

Now, as the facility transitions to housing a redband brood source, the FWP hatchery will focus solely on raising genetically pure Kootenai redbands.

But first, fisheries biologists had to build a wild redband broodstock. To accomplish this, they identified three tributary streams that are home to genetically pure inland Columbia Basin redband trout — the East Fork of the Yaak River; Wolf Creek, located in the Fisher River drainage; and Bear Creek in the Libby Creek drainage.

“There’s redband genetics scattered across the landscape, but because of the stocking of coastal rainbows, they have mostly hybridized,” Stephens said. “So, it’s tough to find those isolated populations where the redband genetics are still pure. We did a lot of research to identify historic stocking efforts and locate lakes where barriers, like waterfalls or culvert barriers, have prevented upstream migration of other species, and therefore prevented hybridization with those isolated redband populations.”

“Our approach moving forward involves individually marking and testing each fish so we will be able to hand select only the pure individuals,” he continued. “Last month marked the first recent spawn of wild redbands in the hatchery to develop a brood source. Some of the recently hatched fish will be held at Murray Springs for four years, which is when we hope to hit full production mode.”

Because the state doesn’t stock moving waters, biologists will be looking to identify alpine lakes in which a redband population can thrive. “If there are mountain lakes at the head end of drainages that we can convert to native redband trout fisheries, that would be an opportunity to improve their status on the landscape,” Stephens said.

Murray Springs Fish Hatchery was built in the late 1970s by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to mitigate for habitat and fisheries losses caused by construction and operation of Libby Dam. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers continues to fund and maintain the Murray Springs facility while FWP operates and manages the facility. The main mission for Murray Springs is to provide fish for Lake Koocanusa and other waters in the Kootenai drainage.

Jim Vashro, president of Flathead Wildlife Inc., and the former regional director of FWP’s northwest Montana office, said the agency’s desertion of its Gerrard stocking program in favor of establishing native redband fisheries signals “a real shift in management” that not all recreational anglers will support.

“There’s big tradeoffs to promoting native fish species over trophy fish,” Vashro said. “On the one hand, redbands are one of the more imperiled fish species in Montana when you look at their distribution. On the other hand, this represents a major change to recreational fishing, and it hasn’t been vetted by the public.”

For Dunnigan, it’s a logical management shift. For one thing, the hatchery-raised Gerrard rainbows have, since 2010, come from triploid broodstock, meaning they’re growing infertile trout that don’t produce in the fishery.

“What we know from the last decade-and-a-half of putting triploid fish in Koocanusa is that most of the fish caught in the large rainbow fishery are wild spawned fish, and we know that most of that spawning occurs in Canada,” Dunnigan said. “I can say that with a high degree of confidence.”

For another thing, raising lunkers like Gerrard rainbows is resource intensive and takes up most of the hatchery’s raceway space because each year-class must be isolated.

“Because Gerrards are long-lived, late-maturing trout, the hatchery does not have adequate space to raise them along with the redbands,” Jason Nachtmann, FWP’s hatchery manager at Murray Springs.

Dave Blackburn, whose Kootenai Angler fly shop near Libby is a staple for serious trout anglers in the region, said he supports the conservation effort so long as the stocking is limited to the lakes.

“I’m all for it,” Blackburn said.

When it comes to identifying potential strongholds for future redband populations, Dunnigan said it will require careful analysis and habitat selection, buy-in from the public and authorization from the state Fish and Wildlife Commission. But without intervention, the redbands aren’t likely to return on their own. If biologists define genetic purity as trout with 90% redband genetics, then the species occupies just 15% of its historic range in the Kootenai.

“If you’re in the camp of purists who think a redband has to have 95% or 99% genetics to be considered pure, then that historic range distribution figure is going to be even lower,” Dunnigan said. “But we know they can persist here. That’s why this is such a golden opportunity to improve the distribution of redbands in the Kootenai and do something meaningful. You pick the battles that you think you can win, the ones that have the greatest chances of success, that have the greatest chance of opening those numbers up. That is the space that we work in.”