The Tragedy in Tunnel Creek

Twenty years ago, a small plane carrying a team of U.S. Forest Service employees departed for a backcountry airstrip in the Bob Marshall Wilderness, never to return. Authorities put out word that no one had survived the crash; 48 hours later, two young foresters emerged from the wilderness and hailed down a passing motorist on U.S. Highway 2.

By Butch Larcombe

On Sept. 20, 2004, a pilot and four passengers in a single-engine Cessna 206 left Glacier Park International Airport and headed for Schafer Meadows, the site of the only public airstrip in the mountainous, remote 1.5-million-acre Bob Marshall Wilderness complex.

Located along the upper stretch of the Middle Fork of the Flathead River in the 287,000-acre Great Bear Wilderness, the northernmost chunk of the Bob, Schafer Meadows is a popular jumping off point for river runners, hikers, pack trips and those seeking to venture deep into wild country. Surrounded by mountains, Schafer and its 3,200-foot turf airstrip is a prized destination for some pilots and one that requires an advanced degree of mountain-flying acumen.

“On a (difficulty) scale of one to 10, flying into Schafer on a beautiful summer morning is like a six or a seven,” says John Paul Noyes, chief pilot at Red Eagle Aviation in Kalispell. “When you get winds and a heavy plane, it’s more challenging, more like a nine. Winds can be a significant challenge back there. And there are not a lot of options if you have mechanical problems.”

Noyes estimates he has flown into Schafer 700 to 800 times, typically flying a route southeast from Kalispell using the lowest passes over the mountains. The route also includes several possible landing spots or places to safely turn around if weather or other issues arise. Flying the same route also helps pilots become familiar with landmarks on the ground, knowledge that can be critical in low-visibility conditions.

The preferred Red Eagle route into Schafer, which first crosses the mountains at Red Owl Pass east of Bigfork, is often not an option when clouds limit visibility. Plan B is a more northerly route up Bad Rock Canyon and above the Middle Fork of the Flathead to a few miles beyond Essex, where the river bends south toward Schafer Meadows.

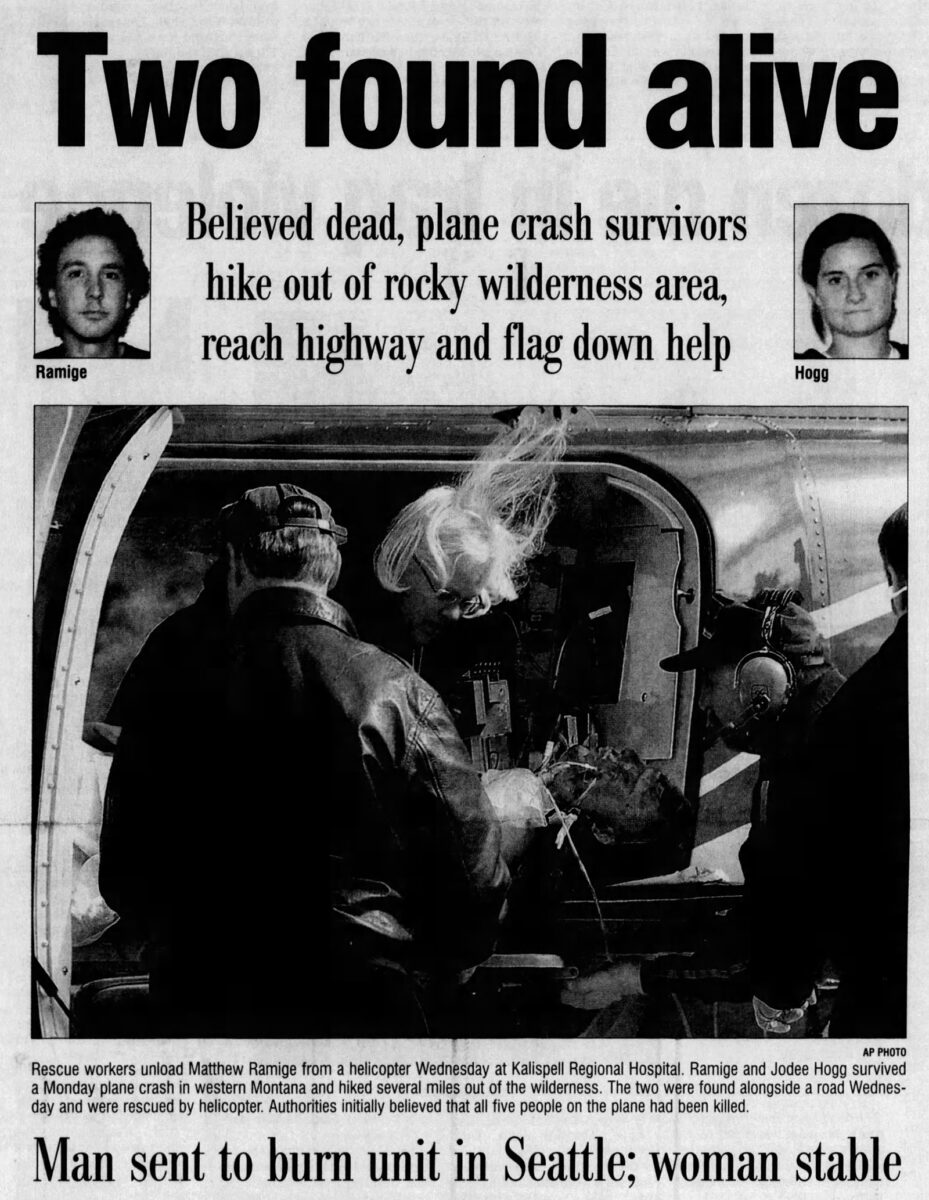

The plane that left the Flathead Valley on that fall day nearly 20 years ago intended to follow the Plan B route. The passengers were U.S. Forest Service employees, while the pilot worked for a fixed-base operator in the Flathead with a contract with the federal agency. Three of the passengers — Jodee Hogg, 23; Matthew Ramige, 29; and Davita Bryant, 32 — were planning to work in the wilderness on a vegetation inventory for several days, while the other passenger, Ken Good, 58, intended to repair electronic equipment at Schafer and fly back with Jim Long, the 60-year-old pilot, that same day.

After delaying the flight for two hours because of unsettled weather, including low clouds, rain and thunderstorms, unusual for late September, the plane departed at about 3 p.m. and headed northeast, its planned route up the Middle Fork and into the wilderness airstrip. A pilot who had taken the route into Schafer earlier that day later told investigators that with rain, low clouds and limited visibility, much of the steep terrain in the Middle Fork looks the same. “If you don’t know it,” he said, “it would be really easy to go up the wrong draw.”

At about 3:15 p.m., pilot Long, using a Forest Service frequency, radioed in that the plane was past Essex and turning south towards Schafer. Not long after the turn, Jodee Hogg, who wore a headset, reported hearing Good, who sat next to Long, ask the pilot, “is that the Middle Fork?” Long’s answer: “Yes, that’s the Middle Fork.”

At about 3:30 p.m., a Forest Service employee in the Tunnel Creek drainage near Pinnacle, about six miles northwest of Essex, reported that he had heard the pilot’s radio transmission and shortly thereafter spotted a plane flying up the drainage where he was working.

The upper portion of the Tunnel Creek drainage has been described as “a box canyon with an entrance but no exit” with an imposing 8,000-foot peak, Mount Liebig, punctuating the basin. Investigators from the National Transportation Safety Board and the Forest Service later concluded that Long, likely battling rain and mist, with ridgetops obscured by clouds, eventually realized he was in the wrong drainage and attempted to make a left turn to reverse course.

Moments later, the plane hit a steep mountain slope at 6,600 feet and flipped on to its top, flames shooting from the craft before it slid to a stop in the rocky terrain. At about the same time, two bowhunters in the Tunnel Creek drainage said they heard an airplane, its engine laboring, then “two pops, then nothing.”

“All in all,” Hogg later told Good Morning America host Diane Sawyer and a national TV audience, “the crash was actually pretty fast. I just remember the impact, there was a loud noise, there was a fire, and I was trying to get my seatbelt undone.” In her introduction to the segment, Sawyer described the crash as “so devastating authorities said no one could ever survive,” words that hinted at the cascading events that characterize the tragedy in Tunnel Creek.

After freeing herself, Hogg told investigators that while the plane was burning, she worked to free Ramige, whose foot was trapped under a seat. “I don’t know if I could have gotten out of the plane by myself,” he would say later. Soon, flames fully engulfed the wreckage. Bryant, who sat behind Hogg and Ramige, died in the plane, as did Long, after he pushed the injured Good out the passenger-side door.

The three who escaped from the plane incurred injuries of varying severity. Along with significant burns, Good had a broken leg. Ramige had serious burns and a fractured spine. Hogg also had burns and an injured back and foot. While warm clothes, food, sleeping bags and a satellite phone were packed for a planned stay in the wilderness, the equipment was destroyed by flames.

Hogg was able to gather a few pieces of the wrecked plane to build a shelter to help shield the three from the snow and cold. “We used body heat to stay warm,” she told Sawyer, her TV interviewer. “Matt didn’t have a shirt because his had burned off. So we kind of did like a Matt sandwich between Ken and I and we just held onto each other all night, and talked about how they would come get us.” Help never came. Good, who had been appointed the “chief of party” responsible for the safe arrival of the Forest Service crew per agency policy, died near daybreak.

While a search for the plane and its passengers was started shortly after it was determined missing, the early effort was focused on the plane’s planned route to Schafer Meadows via Essex. A helicopter pilot taking part in the search reported flying up Tunnel Creek en route to the Schafer area but said he was forced to turn around due to poor visibility before reaching the elevation of the crash. The reports of a plane in Tunnel Creek prompted a search by Forest Service personnel but was not shared with other searchers until the next day. Similarly, the bow hunters who heard the plane and possible sounds of the crash didn’t share that information until late the next morning when they encountered search parties.

The plane wreckage was spotted by ground searchers the next day, Sept. 21, at about 1:45 p.m. Searchers reached the crash site by helicopter shortly after 3 p.m. Finding the plane almost totally consumed by fire, the deputy Flathead County coroner within minutes relayed his conclusion that there were no survivors. That determination ended the search and officials began notifying families of the fatal outcome.

Hogg and Ramige later told National Transportation Safety Board investigators that they heard and saw aircraft, including a helicopter, the day after the crash. “So we waited, but they never came down to us,” Ramige told investigators. “I just remember Jodee and I were really confused as to why they didn’t land, because we thought they had seen us.”

Added Hogg: “I guess I just don’t understand why, why they stopped looking. I understand that the plane had been burned, but both the bodies were clearly visible. And just the fact that Ken was outside the plane, you know, intact, and knowing that there were five people and there were footprints all over in the snow, I guess I just wonder why we didn’t get picked up on Tuesday (the day after the crash).”

When rescuers didn’t arrive, Hogg and Ramige decided to leave the crash site and head down the Tunnel Creek drainage in search of help. The injured duo slowly made their way across steep slopes and over rocks and downed trees before eventually reaching a trail. After another cold night huddled in the woods, they continued downhill. All told, the trek of about five miles took 29 hours, with Hogg encouraging Ramige, the more severely injured of the two, to keep going. “I don’t know if I could have done it myself,” he said later.

Taking frequent breaks, the pair forged ahead. When they heard a train, they realized they were getting close to the tracks along the Middle Fork. They reached U.S. Highway 2 and were able to flag down motorists who summoned help at about 2:40 p.m. on Sept. 22, almost 48 hours after the plane hit the mountainside.

The news of the appearance of the two Forest Service employees declared dead traveled quickly up Tunnel Creek. Jim Dupont, the Flathead County sheriff, was at the crash scene, where fire had melted much of the plane, when he got the news. “We had a lot of very experienced people up there, and no one even remotely imagined survivors,” the sheriff told a reporter. “I’ve been at this a whole lot of years and I can honestly say I’ve never seen anything like it. It’s as close to a miracle as it gets.”

Another round of calls was made to the families of the two survivors. “We were putting together his obituary,” recalled Wendy Becker, Ramige’s mother. “You almost wanted to say ‘is this a cruel hoax? Are you kidding?’ It’s so unbelievable.”

Officials said snow had largely melted at the scene of the crash and they saw no footprints or any other evidence that Hogg and Ramige had left the site. They also theorized that Good, the front-seat passenger, could have been thrown from plane by the force of the crash. After getting the news of survivors, Dupont said he and others combed the wreckage for more than three hours before finding the unfastened seatbelts where the two sat.

The survival story made headlines not only in Montana but across the country. For Denise Germann, then the public affairs officer for the Flathead National Forest, the days after the crash are etched in memory. Her phone rang at all hours as media outlets clamored for details and interviews.

“It was my first experience with the national media and it was just jaw-dropping to me,” Germann said almost two decades after the tragedy. “They were just ruthless in trying to get access to the people involved in the story.”

While media relations were part of her job description, Germann and numerous other Forest Service employees were also mourning the loss of Good, a well-liked co-worker, along with the others who died in Tunnel Creek. A number of Forest Service employees served as untrained, de facto counselors for survivors and the families of the victims. “I spent a lot of time at the hospital with one of the survivors,” Germann says. “It was just difficult dealing with people who were going through tragedy. It was one of the most impactful times in my career and in my life.”

Hogg spent several days in a Kalispell hospital, while Ramige was flown to a Seattle hospital where he was treated for severe burns and other injuries, spending 25 days in the burn unit, where he also celebrated his 30th birthday. After the initial media barrage, interest in the story cooled. But weeks after the crash, both survivors shared details and emotions with interviewers.

In her hometown of Billings, Hogg recalled the cold, painful journey down the Tunnel Creek drainage: “I had this feeling that it was absolutely unacceptable to sit down and quit. I also knew it wasn’t my time.” A few weeks later, Ramige told an interviewer in Seattle that he was amazed that he had survived the crash and the subsequent hike to safety. “It’s like being given a second chance, and gaining a new perspective on life. I think anyone who has been close to death would say the same thing.”

In November, about six weeks after the crash, Montana Gov. Judy Martz presented Hogg and Ramige, who was not present, with Montana Medals of Valor for their actions to help Good and others in the crash. A medal was also presented to Laura Long, the wife of the deceased pilot, in recognition of his effort to haul Good out of the burning plane. The medal honoring the pilot didn’t sit well with some, including Brian Byrant, whose wife died in the crash. In an Associated Press interview the day before the medal presentation, Bryant said he blamed Long for the crash and noted that the investigation into the events surrounding the crash had yet to be completed.

“I think it’s pretty callous of the governor’s office to just say this guy is a hero without looking into the whole situation,” Bryant said. “One action shouldn’t override a whole series of bad decisions that cost people their lives … that plane should have never left the ground.”

Those killed were memorialized in the weeks after the crash. Davita Bryant, who lived near Whitefish, was remembered for her love of the outdoors, live music, dancing and yoga. Good, a longtime Forest Service employee who was a few months from a planned retirement, was recalled as a devoted family man but one with an insatiable passion for railroad history and photographing trains. Long, a retired chemist and corporate executive, was an avid aviator who volunteered for the Civil Air Patrol and with Angel Flight, a program that flew patients and families in need of medical help.

The investigation report from the National Transportation Safety Board that came about a year after the Tunnel Creek crash cited the poor weather and the actions of Long. The report noted that Long, who had more than 2,700 hours of cockpit time, had flown to Schafer Meadows four times during the month of the crash, logging all his flights in the Cessna he flew on Sept. 20. But the agency concluded the pilot was either “lost or disoriented” when he turned into Tunnel Creek on that stormy day in 2004.

In a separate investigation, the Forest Service cited the need for better flight communication procedures and suggested that all agency passengers on future flights wear fire-resistant clothing. It also admitted that Long appeared to have been wrongfully approved to fly Forest Service employees in the backcountry terrain on the route to Schafer. The agency requirement was for at least 200 hours of such experience; records showed Long had just 14 hours.

In 2007, about three years after the deaths in Tunnel Creek, Organizational Dynamics, an academic journal, published an article titled “Missed Opportunities: The Great Bear Wilderness Disaster.” The author was Wendy Becker, Matt Ramige’s mother and a business management professor at a university in New York.

Noting her contention that the crash was not a straightforward “wrong place at the wrong time” event, Becker outlined three critical factors that, in her opinion, had outsized ramifications: the pilot’s wrong turn into Tunnel Creek, the lack of communication that misdirected and slowed the search for the plane and survivors and the premature declaration that no one had survived the crash.

Her purpose in the dissection of the crash: “We need to better understand how multiple small errors become chained together … leading to disaster.”