Every reporter should have a rolodex filled with people who are good for a quote — whether it’s about something happening on the city council or a bit of local history. For more than a decade, when I was covering Glacier National Park as a reporter for the Flathead Beacon, my go-to on the latter was Ray Djuff.

Working on a story about the 100th anniversary of the Many Glacier Hotel? Call Ray. Need a few words about a historic chalet threatened by a wildfire? Ray again. Wanna know how automobiles got around the park prior to the construction of the Going-to-the-Sun Road or U.S. Highway 2? Yep, you guessed it, Ray is your man.

By the way, if you’re looking for the answer to that last question, it can be found within the pages of Ray’s latest book, “Glacier’s Reds: The Quest to Save The Park’s Historic Buses.” Over the last 30 years, Djuff has authored or co-authored some of the most seminal titles about development within Glacier and Waterton Lakes national parks, including “High on a Windy Hill: The Story of the Prince of Wales Hotel” and “View with a Room: Glacier’s Historic Hotels and Chalets” with co-author Chris Morrison.

“I don’t know of anyone who is more knowledgeable about the history of human activity within Glacier National Park over the last 130 or so years than Ray,” said friend, author and historian Scott Tanner.

Ray’s journey to becoming one of Glacier’s preeminent historians dates back more than a half-century when he got a summer job working behind the bar at the Prince of Wales Hotel slinging drinks and answering questions for thirsty vacationers.

Ray does not remember his first trip to Glacier National Park but he knows it was sometime in the late 1950s, when his father was in the Canadian military. Ray was born in Calgary in 1954 but bounced around because of his father’s career, spending time stationed at various military posts across western Canada. The trip through Glacier likely came during a drive back to Calgary from Vancouver. At the time, it was faster to drive south through the United States to get home than to drive through the mountains of British Columbia. The family also did tours in Germany, the first in 1962. At the time, World War II had ended just 17 years earlier and signs of the conflict were still evident; “The pockmarks of bullets were still everywhere to be seen,” Ray recalled. It was in Germany that Ray became fascinated with history.

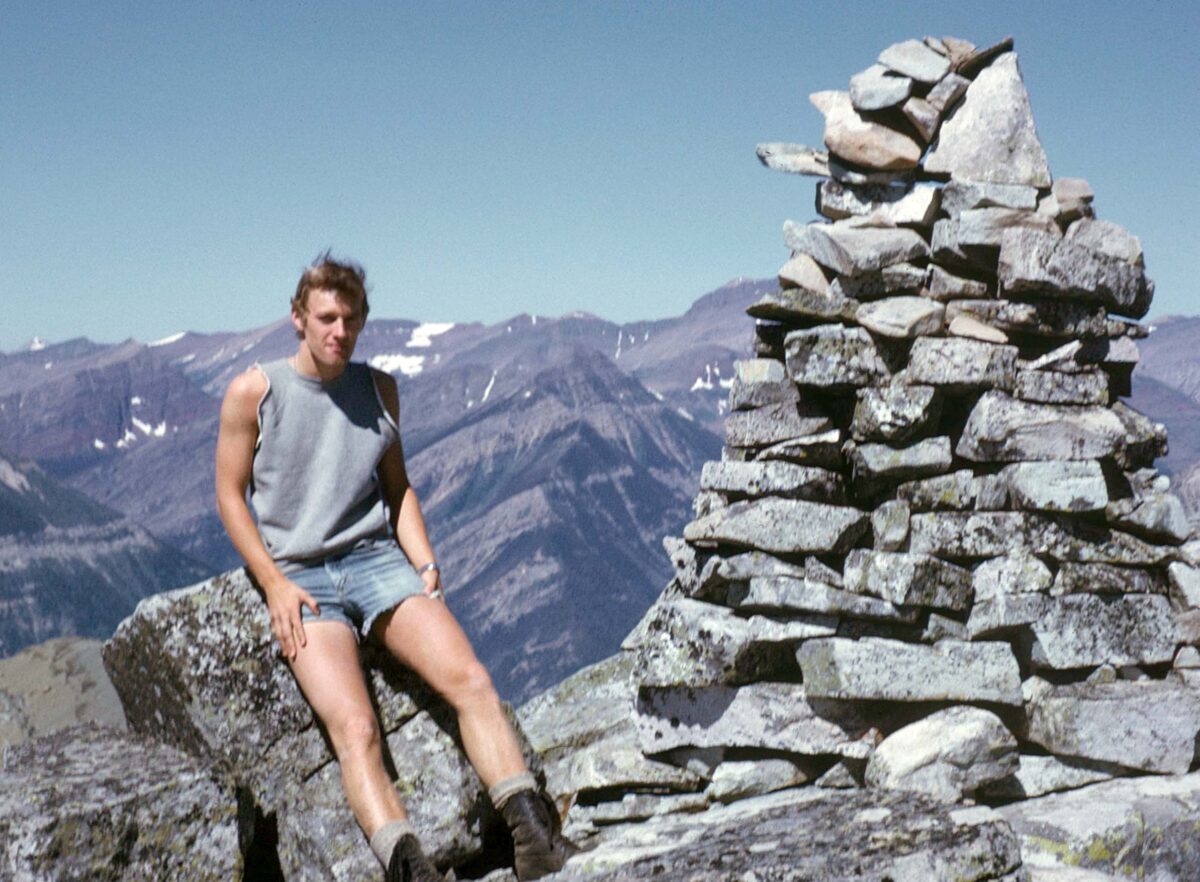

If Germany is where Ray fell in love with history, it was back home in Canada where he fell in love with the mountains. In 1970, Ray was in the Army Cadets and spent six weeks in Banff National Park hiking, climbing and building a deep appreciation for the rugged landscape.

After years of bouncing around because of his father’s career, Ray decided to attend the University of Calgary to better get to know his native city. Following his first year in school, Ray went out in search of a job that would allow him to spend more time in the mountains. While Banff, an hour and a half west of Calgary, would have been an obvious choice, Ray decided to apply for a job in a place he had never been, Waterton Lakes National Park. In the summer of 1973, he started a job as a busboy and, later, as a bartender at the Prince of Wales Hotel. The Prince of Wales was the last of a series of lodges and chalets constructed by the Great Northern Railway in the 1910s and 1920s. The railway had first proposed constructing a hotel at Waterton Lake in 1913 — at about the same time it was building facilities like the Glacier Park Lodge and Many Glacier Hotel — but the plans were shelved because of the outbreak of World War I in 1914 and a proposed dam that put a halt to all building in Waterton for three years. The hotel would have likely never been built had it not been for the enactment of the Eighteenth Amendment, prohibiting the manufacture, sale or transportation of alcohol. Wanting to ensure that visitors could still enjoy a cold one while on vacation, the Great Northern set out to build Prince of Wales on the shores of Waterton Lake in 1926. The 90-room hotel opened the following summer as a “haven for thirsty Americans.” With its picturesque location and whimsical design, the structure never fails to impress. More than 50 years later, Ray still remembers the first time he set eyes on the place.

“I was awed by the hotel itself,” he said. “When you’re in the parking lot looking up it’s so imposing. Obviously, it’s not as big as the mountains but it seems that way. It’s jaw-droppingly beautiful. It’s inspiring.”

Ray’s time as a busboy was brief and he was quickly promoted to bartender. Tending bar meant Ray was asked all sorts of questions, from “What time do they let the animals out” to “How much does that mountain over there weigh.” But on occasion, some people bellied up to the bar asked some tough ones. Ray and the other employees knew the basics about the hotel — that it was opened in 1927 by the Great Northern — but beyond that, there were many unanswered questions. A small booklet about the park made a brief mention of the hotel, but that was about it. However, in 1973, the hotel was only 46 years old and many of the people who helped build it were still around town. Curious to learn more about the hotel himself, he hit the streets on his days off — when he wasn’t off hiking.

“On my days off, I’d go knock on doors and talk to people,” he said. “Through that, I was able to piece together a history of the hotel.”

Ray worked at Prince of Wales throughout college. In school, he took on several writing projects about the hotel and the park in general. As he performed more research, his interest in the subject grew. In 1977, he made his first trip to the National Park Service archive in West Glacier. It was there that he learned that the Great Northern Railway (by then merged with the Northern Pacific; Chicago, Burlington & Quincy; and Spokane, Portland & Seattle railroads to form the new Burlington Northern) had turned over much of its corporate archive to the Minnesota Historical Society.

Knowing that the archive might hold the answers to many of his questions about the development of the lodges and chalets inside Glacier and Waterton Lakes national parks, he decided to take a road trip to St. Paul, Minn. It was there he found the answers he had been looking for about the development of Prince of Wales, plus a whole lot more.

“Seeing the Great Northern files was very exciting to me,” he said. “It finally felt like I understood the entire story.”

In 1980, Ray graduated with a journalism degree from the Southern Alberta Institute of Technology and soon started working for a newspaper in Fort McMurray. While he was busy, the new job and his new family (Ray and his wife Gina had two children) didn’t put a damper on his desire to research and write about the park. By then he had gathered a huge amount of material that he wanted to turn into a book. But finding a publisher for such a title proved challenging in the mid-1980s as interest in Waterton Lakes — which was essentially a regional park — was limited. Finally, Ray approached the Waterton Natural History Association about the idea. It was there he met Chris Morrison, a fellow journalist and board member of the association. She too was interested in the history of the hotel and championed the idea of Ray authoring a book about it. Chris also came on as an editor for the project, the first of many collaborations between the two.

Chris said she and Ray are both “dedicated to the past” and have similar working styles. They also share a preference for working with original source material, meaning their books often chart new ground and rarely rehash past efforts. In 1991, the Waterton Natural History Association published “Prince of Wales Hotel,” the first comprehensive history of the lodge. Two years later, they co-authored “Motor Vessel International” about the boat that has traveled back and forth over Upper Waterton Lake between the two parks since 1928. Later, in 1999, a new book about the Prince of Wales Hotel titled “High on a Windy Hill” was published as well. As time went on, Ray’s interests expanded, and so did his research efforts.

“The Prince of Wales got me interested in the other lodges and then I got interested in the Blackfeet Tribe and their relationship with the Great Northern Railway. And then that led to the buses and so on and so on,” he said. “It really just snowballed.”

The next project would be the most ambitious yet: a complete history of the Great Northern’s properties in Glacier and Waterton Lakes national parks co-authored with Chris. Published in 2001, “View with a Room: Glacier’s Historic Hotels & Chalets,” would in many ways become the seminal volume about the railroad’s footprint in the park. The 168-page book chronicles the rise and fall of the lodges through detailed profiles of each structure. After an initial hardcover offering, it would be reprinted as a softcover.

In the decade that followed, Ray wrote numerous articles and collaborated with Chris on other books, including “Waterton and Glacier in a Snap!” (2005) and “Glacier from the Inside Out” (2012). All the while, Ray continued to work as a journalist in Alberta, including stints at the Calgary Sun and Calgary Herald. Ray said none of the books or research would have been accomplished without the support of his wife, Gina, who never batted an eye when he headed out the door for an extended research trip; “It couldn’t have happened without Gina’s cooperation,” he added.

In 2012, Ray was laid off by the Calgary Herald, and while he considered staying in journalism, he instead got a job as a cheesemonger. It was a dramatic change in career, but his time as a journalist prepared him well for it, especially in researching the different types of cheeses. He was so good, in fact, that a rival store hired him away to open new shops in Calgary and Edmonton. He attributed that success to his storytelling abilities, entertaining shoppers while preaching about the differences between Parmigiano Reggiano and Padana. He retired from that job in 2020.

But Ray did not retire from research and writing, and when he left cheesemongering he was in the midst of one of his biggest research projects yet: piecing together a history of Glacier’s iconic red buses. A few years earlier, Ray had been deep in an effort to research Two Guns White Calf, a Blackfeet chief who had been hired by the railroad to help promote the park. The project had become all-encompassing, and Ray was looking to do something a little different, so he began to dig into the red bus story.

The story of Glacier’s famed red buses dates back more than a century to 1914 when Glacier Park became the first in the United States to offer motorized tours. Through the 1910s and 1920s, the Glacier Park Transportation Co. employed a variety of touring buses, but its most famous, the White Motor Company’s Model 706, would arrive in 1936. The 706 touring bus was popular throughout the western National Parks, but as the decades went on only the Glacier fleet survived mostly intact (of the 35 built between 1936 and 1939, 33 are still on the road today).

As with any project, Ray tracked down as much information as he could, pulling together material from archives in Montana, Wyoming and Minnesota. He also was able to secure the personal papers of key players in the red bus story, shedding new light on the topic (perhaps most notable were the papers of Roe Emery, who helped create the Glacier Park Transportation Co.). Before long, Ray knew he had the makings of his next book in hand. While Ray worked feverishly on the book, things in his personal life took precedence, most notably the passing of his wife Gina after a battle with cancer. Another challenge was the pandemic that closed the U.S.-Canada border and prevented Ray from making much-needed research trips until 2022. Finally, in March 2024, Ray was able to publish the long-awaited volume. So far, it has been well received.

“I think ‘Glacier’s Reds’ will stand for decades as the Bible of the red buses,” said friend, author and historian Scott Tanner. “I don’t see anyone doing something as well researched as this and it’s exemplary of everything Ray does.”

Scott met Ray in the mid-1990s after he had written a story in the Great Northern Railway Historical Society’s journal and Ray reached out with some additional questions; “It didn’t take more than a few minutes to realize that we had a lot in common and a great friendship blossomed from there,” Scott said.

Scott noted that Ray has done more than record Glacier’s history — he’s become a part of it. When the National Park Service rebuilt the Sperry Chalet following a devastating wildfire in 2017, Ray knew where the original plans for the building were.

“I’ve acquired a lot of useless knowledge that every once in a while becomes pretty useful,” he said.

Fifty-one years after he first got a job at the Prince of Wales Hotel, Ray said he’s just as fascinated as ever about Glacier and Waterton Lakes national parks. And he still gets a “thrill” chasing down answers that help people better understand these beloved landscapes, no matter how small. Recently, during a visit to the Belton Chalet, Ray took a visitor down to the basement to look at a large signature written on the foundation wall. In old German script, someone had written “Lores – Aug. 15, 1913.” Ray said that was the summer the chalet opened, so it’s possible that a contractor painted their name on the wall, although there’s no record of one by that name. While one might think the calligraphy would suggest someone of German descent, Ray isn’t so sure. That’s because the nine in 1913 does not have an extended tail, which is common in Old German script.

Questions like who put the moniker on the foundation of the Belton Chalet are what keeps Ray going. He said at 70 years old, he’s got enough research and writing projects to keep him busy for decades to come.

“Some people wonder what they’ll do in retirement, but I wonder how I can live long enough to finish all the projects I’ve started,” he said.

It’s hard to understate Ray’s contribution to the study of Glacier Park history. But perhaps the best example is an analogy that National Park Service historian Deirdre Shaw once shared with him.

“Deirdre said the publication of ‘View with a Room’ was a blessing for her,” Ray said. “She no longer had to spend time providing a historical overview of Glacier to researchers and reporters, instead telling people making inquiries to buy a copy of ‘View with a Room,’ read it and, once they had digested it, to pose any remaining questions.”

As luck would have it, I was one of those reporters. And I‘ve been bugging Ray for quotes ever since.

“Glacier’s Reds: The Quest to Save the Park’s Historic Buses” by Ray Djuff and published by Goathaunt Publishing can be purchased through Amazon.com or local booksellers.