As Community Services Collapse, Experts Say the Mentally Ill are Being Left Behind Bars

The closure of mental health crisis centers in the Flathead Valley has created a backlog of criminal cases involving mentally ill defendants, overwhelming the courts and leading to a growing waitlist for evaluations and treatment at the Montana State Hospital. According to experts, incarceration is the default for mentally ill defendants.

By Maggie Dresser

When Columbia Falls Police Department officers found Zain Glass on Sept. 20, 2022, he was outside the house he shared with his mother and sister clutching the knife he’d just used to stab his sibling’s 22-year-old boyfriend in the stomach.

In interviews with detectives, Glass insisted the stabbing was accidental, and that he overheard the couple arguing. He later told a Flathead County judge that he attacked the man to protect his sister.

The victim, Lukas Davis, died shortly after the attack and Glass was charged with a felony count of deliberate homicide in Flathead County District Court. Two months later, after Judge Robert Allison deemed him mentally unfit to proceed in court, he was committed to the Montana State Hospital in Warm Springs.

Glass remained in Warm Springs for almost a year-and-a-half, a timeframe during which he received a court-ordered fitness evaluation to determine whether he understood the charges against him. Glass was diagnosed with multiple disorders and Judge Allison ordered involuntary treatment with antipsychotic medication, which the defendant had previously refused. Meanwhile, Glass’s public defenders in Kalispell said prosecutors missed multiple court deadlines and hearings as delays at the hospital persisted, prompting them to request a case dismissal.

In 2023, Glass’s public defender Dianne Rice argued Glass was “unable to understand the proceedings against him or assist in his own defense and therefore [could not] be tried, convicted, or sentenced.” She also argued that ongoing delays at the state hospital and at the county attorney’s office, which included missed fitness evaluation deadlines and a failure to request hearings, rendered the case dismissible.

“The state is going to allow him to languish indefinitely, and that’s not how we treat the mentally ill in Montana,” Rice said at a July hearing 2023.

More than six months later, officials determined Glass was fit to proceed in court and the defendant was taken back to the Flathead County jail. He entered a not guilty plea in February 2024.

The following August, Glass, who is now 25, entered a plea deal with prosecutors after his charge was amended to a felony count of negligent homicide. In October — more than two years after the fatal stabbing occurred — he was committed to the custody of the Department of Public Health and Human Services (DPHHS) to serve a 20-year sentence at the Montana State Hospital.

As of Dec. 11, Glass remained in the Flathead County Detention Center, waiting for a bed to open up in Warm Springs.

Glass’s case is just one example of the consequences stemming from a backlog of court-ordered forensic fitness evaluations and the prolonged waitlist for an open bed at the Montana State Hospital located in Warm Springs.

According to attorneys with the Office of the Public Defender (OPD) in Kalispell, waitlists for a fitness evaluation usually hover around 90 people deep, sometimes running close to a year. Defendants wait out this time in jail before they’ve even entered a plea. In some cases, evaluations can be completed swiftly, but more complicated cases can take a long time, depending on the defendant’s condition.

In Glass’s case, the prosecutor and defense attorneys disagreed on his fitness, which resulted in four separate evaluations over the span of the two-year proceedings.

“When we talk about mentally ill people languishing in custody, what’s important to keep in view is that you’ve got a delay in getting the evaluation to begin with and then after you get the evaluation and everybody agrees they should go to the state hospital for restoration, you’re looking at maybe a year wait,” Kalispell OPD Manager Nick Aemisegger said. “Then if somebody is convicted and they are found guilty but mentally ill — then they need to go there for sentencing. That’s another wait.”

Because of the absence of mental health services in the Flathead Valley, Aemisegger says cases involving mentally ill defendants have skyrocketed in recent years as resources dry up and funding remains scarce, despite the $300 million that DPHHS allocated toward mental and behavioral health during the 2023 Legislature.

“I have heard from every attorney in the office that it is worse now than they can ever remember it being in terms of the number of clients they have that are seriously mentally ill, and they just have a hard time finding resolutions,” Aemisegger said.

Aemisegger said the lion’s share of cases in his office that are related to mental illness aren’t as extreme as Glass’s. Rather, they more often involve misdemeanor charges like theft, criminal trespass and criminal mischief, while most of the felony charges involve criminal drug possession. But despite the pettiness of many of the crimes, a high volume of them requires a fitness evaluation in order to proceed in court. And because of the growing backlog, that means the length of time a client spends in jail waiting for an evaluation is often longer than their sentence would have been.

Flathead County Attorney Travis Ahner, too, said the volume of felony cases involving mentally ill individuals has spiked; he recalls only seeing one or two per year when he was first elected in 2018. Because of the increase, minor crimes often go unaddressed, and many mentally ill defendants never make it to the state hospital, instead passing through a revolving door back into their communities, where resources for treatment are scarce or nonexistent.

“For the average trespass or smaller crimes, they don’t have the space,” Ahner said. “For people committing very serious crimes or sitting on homicide charges, if they are hard-pressed to address that population, there’s no way they will address the low-level folks who are no less suffering from mental illness.”

Due to the prolonged wait times, attorneys representing clients accused of minor crimes, like theft or trespassing, often do not even bother presenting mental illness as an element of their defense.

“When you’re looking at something where maybe the penalty is six months in jail, it’s hard to think that you’re going to sit in jail and wait more than six months potentially to go to the state hospital,” Kalispell public defender Alisha Rapkoch said.

But for clients with severe mental illness or defendants who have committed serious felonies, attorneys have an ethical obligation to request a fitness evaluation if the defendant does not understand the proceedings.

“If you raise this thing that’s called ‘unfitness,’ it requires us to get an evaluation,” Rapkoch said.

According to Flathead County District Court Judge Amy Eddy, the volume of civil involuntary commitments, which are categorized as people who are suicidal, homicidal or unable to take care of daily activities, has dramatically dropped in recent years. This year, there were only eight involuntary commitments in Flathead County.

“These people usually wind up at the emergency room at Logan Health due to law enforcement involvement,” Eddy said, describing a hobbled mental healthcare landscape bereft of services. “Maybe they’ve been accused of committing a crime or they’re not dressed appropriately; those people are admitted to the emergency room. We have had a precipitous decline in the number of cases.”

But while the civil commitments have dropped, the waitlist for criminal commitments continues to rise. As of late November, there were seven Flathead County defendants waiting in jail to be transported to Warm Springs for an evaluation. The women’s waitlist is even longer because there are only eight beds at Galen, the forensic unit of the state hospital where evaluations are conducted. Women are also typically more complex to treat because they are often victims of pervasive violence. One Flathead County woman has been waiting in jail since August 2023.

“The waitlist for the state hospital is a crisis,” Eddy said.

Eddy says while some defendants suffering with mental disease are still fit to proceed in court, there’s a segment of the population suffering from such profound mental illness they have no other choice but to go to Warm Springs. Meanwhile, they wait in jail, where detention officers cannot force inmates to take medication until there’s a bed vacancy at Warm Springs.

Statutory deadlines create additional snarls in the system. When a defendant is finally admitted to Warm Springs and begins treatment, the state hospital has a deadline of 90 days to complete fitness restoration. If restoration fails, the criminal case must be dismissed.

“We are blowing those statutory deadlines,” Eddy said. “It’s reached a point where we are getting motions to dismiss cases. When we don’t meet those, we have potential constitutional implications.”

For example, Eddy in September dismissed the case of a Flathead County man diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia whose fitness was not successfully restored. In the order, Eddy wrote that the delays at the Montana State Hospital are “fundamentally unfair and [do] not meet the minimum requirements of due process.”

According to the order, which was redacted to to protect the defendant’s privacy, the defendant pleaded guilty last year to a felony theft charge and was given a three-year deferred sentence along with a mental health evaluation and treatment recommendations; however, due to the defendant’s schizophrenia, he had previously been admitted to the state hospital 13 times since his diagnosis and initial stay in 2003. He has remained homeless since his first release from the state hospital more than 20 years ago and refuses to take his prescribed antipsychotic medication.

In July, a psychiatrist deemed the defendant unfit to proceed because he did not understand the charges against him, and he was therefore unable to assist his attorney with the case.

“In a case such as this where the Defendant is not fit to proceed and likely requires the administration of involuntary medication for fitness to be restored, there is no other mechanism to facilitate the Defendant’s restoration,” Eddy wrote in the order.

From the time of the charges in January 2023 until the case’s dismissal in August 2024, the defendant had been in custody for 225 days, 161 of which were due to delays at the state hospital.

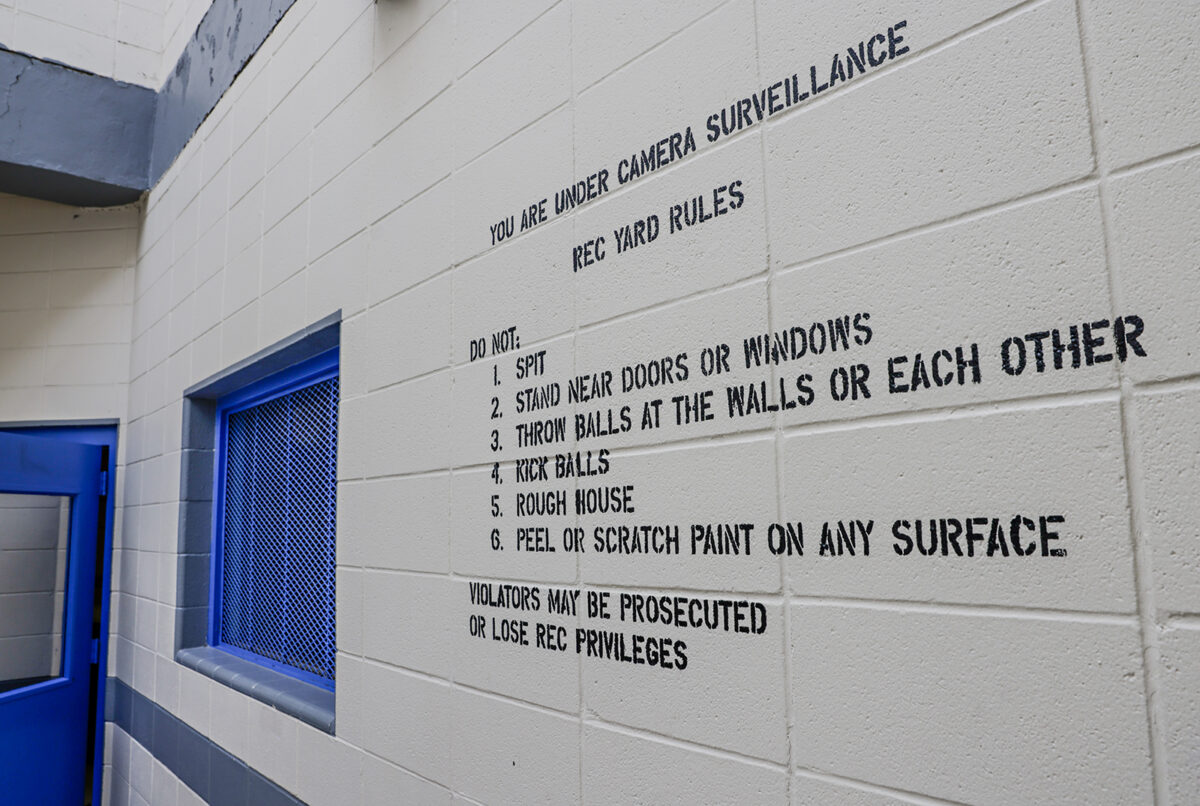

On the medical wing of the Flathead County Detention Center, the sound of inmates pounding on the walls, kicking doors and yelling echoes through the hallway at any given hour of the day.

During the first 72 hours in jail, mentally ill inmates who are violent or at risk of suicide are held in a windowless receiving cell wearing a “safety smock,” a thick garment that cannot be rolled or folded in a way that could be used as a noose or to inflict self-harm.

Even after the first three days, these inmates require single-cell occupancy because of their violent behavior and suicidal ideations. While the jail has a total of 154 beds, many of those beds can’t be used because mentally ill inmates, who make up 20% of the detention center’s population, must be housed alone.

“My med wing is overflowing into our receiving cells and they’re completely full of individuals who cannot be housed anywhere with other people,” Jail Commander Jenny Root said. “It’s a staffing nightmare.”

In addition to sanitary issues that regularly arise when inmates smear bodily fluids on the walls, Root said she calls the plumber multiple times per week when inmates flush objects down the toilet, causing frequent flooding.

While many of the disruptive inmates are prescribed antipsychotic medications, jail staff can’t force them to take their medication.

“We have quite a few inmates that have already been to the state hospital,” Root said. “We’ve sent them to the state hospital, they’ve gotten released and then they come right back to us because of the lack of resources in our community.”

Root says many repeat offenders start with misdemeanors and eventually wind up with felonies. Some of the same individuals will come back to jail dozens of times after stints at the state hospital over the years because they don’t stay on their medications.

“It’s frustrating. Our hands are tied,” Root said. “They don’t belong in jail. Our goal is to be returning people to the community better and not watching them deteriorate within our facility — especially a county facility. I can’t get the help for mentally ill (people) in a timely fashion unless they deteriorate and they’ve decompensated enough to where it’s a medical emergency.”

Out on the streets, Kalispell Police Department (KPD) Chief Jordan Venezio said responses involving mentally ill individuals consume about 80% of his department’s call volume.

Usually, these initial responses don’t involve arrests. However, individuals suffering from untreated or undiagnosed mental illness often decompensate to the point where their behavior becomes a public safety threat, Venezio said. While some calls are as minor as someone talking to themselves in front of a business, other calls involve violent behavior like assault.

“There’s a large handful of people that get released from jail and we’ll arrest them within six hours,” Venezio said. “On one hand, you’re trying to make sure jail is only utilized for serious offenders, but the moment they’re let out of jail, they don’t have the mental awareness to not re-offend and are immediately taken back to jail. So, it’s frustrating for jail staff to have to work in this environment, but at the same time, they are a danger to public safety. We have to use whatever resource is available to us.”

In recent years, the Flathead City-County Health Department established a Crisis Assistance Team (CAT) program to assist law enforcement and to help de-escalate individuals experiencing a behavioral health emergency. The program has grown to two teams of co-responder crisis therapists and care coordinators who also connect individuals to resources. Although the co-responder’s presence is a relief to law enforcement officers, there are few places to send the individuals in crisis besides jail or the Logan Health emergency room.

“There are not a whole lot of places where they can actually get them help,” Venezio said.

Social workers, law enforcement officials, attorneys and lawmakers all trace the lack of mental health resources back to the 2017 special session at the state legislature when more than $50 million was cut from the DPHHS budget.

Behavioral and mental health funding was slashed and essential community-based services, like crisis stabilization facilities, struggled to survive. The loss of the Case Management for Adults and Children program was detrimental to the most vulnerable clients, who suddenly lost assistance with basic necessities like filling out government assistance paperwork, medical care, and food and housing. Severely mentally ill clients didn’t have anyone to make sure they took their medication.

While some crisis stabilization centers stayed afloat for a few years following the budget cuts, the five-bed, in-patient facility called Glacier House in Kalispell shut down in 2021 due to staffing shortages, due in large part to a low Medicaid reimbursement rate. Affiliated with Western Montana Mental Health Center (WMMHC), the Glacier House provided resources for individuals experiencing a mental health crisis like suicidal ideations and other intensive behavioral health interventions.

Following more than a year of attempts to reopen the center, the former CEO of WMMHC suspended those efforts last year, citing increased costs and a stagnant Medicaid reimbursement rate that made operating nearly impossible. The state-funded service provider closed facilities in Bozeman, Butte and Polson, eliminating 31 crisis beds.

Last year, Sunburst Mental Health in Kalispell closed down after years of underfunding, and following an investigation into Medicaid fraud allegations against an employee.

Currently, the behavioral health department at Logan Health, formerly called Pathways Treatment Center, is the only local in-patient facility where those experiencing a mental health crisis can go. While the 40-bed center provides services like therapy, addiction counseling and medication, the hospital is overwhelmed with the demand.

“Budget cuts dramatically impacted the community mental health services,” Rep. Bob Keenan, R-Bigfork, said, referring to the 2017 budget cuts. “There were provider rate cuts and reductions — that was the beginning of the unwinding of the community system that we had.”

Following the 2023 State Legislature, Republican Gov. Greg Gianforte signed House Bill 872, which invested $300 million to expand community-based systems. The Behavioral Health System for Future Generations Commission, chaired by Keenan, outlined the priorities in a report published this fall that included implementing a statewide crisis system.

While some of that funding is planned to go toward community mental health clinics, $7.5 million was funneled into a near-term initiative that launched in March to address the backlog of court-ordered fitness evaluations.

As part of the initiative, attorneys can now request that an evaluation be completed locally or via telehealth from a list of sanctioned providers instead of at the state hospital in Warm Springs, where the limited capacity contributes to long wait times.

“It’s unacceptable that people who have obvious mental illness are in a county jail — because that’s not mental health treatment,” Keenan said.

As of early December, there have been 37 evaluations conducted in community settings in 15 counties, which officials consider to be “excellent and historic progress,” according to an email from DPHHS spokesperson Holly Matkin.

According to DPHHS officials, there are seven providers regularly conducting evaluations outside the state hospital, which has led to a 24% drop in the waitlist since the program was launched in March.

While the initiative has provided some statewide relief, Aemisegger at the OPD said there is not a single approved provider in Flathead County. The closest evaluator is Dr. Vincent River in Polson, who he described as a “very busy guy” due to the high demand.

Despite the $7.5 million in funding that has been allocated to address fitness evaluations, Aemisegger said his clients continue to wait in jail for months before they can be seen.

“My client, who I know if he were fit to proceed, could have been out of jail within two or three weeks,” Aemisegger said, referring to his mentally ill clients in general terms. “But now the only reason he’s there is because he’s mentally ill — something he didn’t ask to be.”

Through the deinstitutionalization movement in the 1960s and 1970s, government officials envisioned a transition from mental health treatment at state hospitals to community-based facilities.

Following the federal Community Mental Health Act of 1963 and Montana’s Mental Commitment and Treatment Act of 1975, there was an exodus of patients from the Montana State Hospital. They were instead left to obtain treatment from mental healthcare centers within the community, reserving beds in Warm Springs for the severely mentally ill population. WMMHC was established in 1971 as part of this rollout with five clinics that opened in Missoula, Ravalli, Lake, Sanders, Lincoln and Flathead counties.

At its peak in 1955, the Montana State Hospital, which was at one point called the Montana State Insane Asylum, recorded an average daily census of 1,936 patients, according to state data. Now, the hospital accommodates 270 beds, 54 of which are forensic mental health facility beds.

“They deinstitutionalized the state hospital, and they put people into the community where they belonged, but they didn’t fund it,” said Jenny Ball, a licensed social worker and the OPD investigator and mitigator specialist.

To address Montana’s broken mental healthcare system, local officials all agree the Flathead Valley needs case managers and some form of crisis center to address the issues. But many local mental health advocates cast doubt on the state’s plan.

While $300 million in state funding has been allocated to mental and behavioral health, much of the rollout has been unclear. According to the Behavioral Health System for Future Generations Commission report, priorities include improving case management, expanding services and recruiting the workforce.

Officials are working to reopen the WMMHC crisis stabilization center called Glacier House in Kalispell after years of shuttered doors, but the process has lagged as leadership turnover and bureaucratic delays have caused stagnation. After years of turmoil at WMMHC since it closed in 2021, a new CEO was brought on board in November to build a sustainable model and reopen the closed crisis stabilization facilities.

CEO Bob Lopp said reformulating the financial model to provide adequate Medicaid reimbursement rates and recruit and retain qualified staff will be the major obstacles.

“We’re in the middle of those conversations,” Lopp said. “To have it be a sustainable crisis response solution — that will require Medicaid funding. We will need help from government sources and private philanthropists. Let’s not have this just be a two-month model. It’s always one of the challenges when you’re serving these populations. How do you keep the program running?”

As Lopp works with partner agencies to build a sustainable model, it’s unclear when Glacier House and other facilities across the state will open. But in the meantime, members of the mentally ill population continue to cycle in and out of jail and the state hospital, with nowhere to receive treatment following their release.

“They used to get help, and now they’re getting charged,” Ball said. “And it feels like they’re criminalizing mental health decompensation.”