Chasing Tracks and Trails in the Wild Swan

Born and raised in the Swan Valley, Luke Lamar didn’t have to stray far from home to find fulfillment. As a wildlife biologist, wilderness first responder and expert animal tracker, Lamar is promoting conservation and expanding stewardship in the Swan and beyond.

By Kay Bjork

When Luke Lamar explains that he has spent more time exploring the Swan Valley than most people do in 10 lifetimes, it is not to boast. He is just stating fact. And being a scientist, facts are the framework for most of what he does.

He might only be 42 years old, but Lamar has spent most of those years piling up miles and stories in the wild Swan, and he probably knows the land and the animals better than just about anyone. His role as wildlife biologist and managing director at Swan Valley Connections (SVC) certainly benefits from the fact that he is so deeply rooted in the Swan Valley.

He was born at the family home just a few air miles from SVC headquarters. As he likes to tell it, “I took my first breath of Swan Valley air and grew up on the minerals of the Swan Valley when I munched on dirt with a wooden spoon while playing in the sandbox.” You might say he was Montana made.

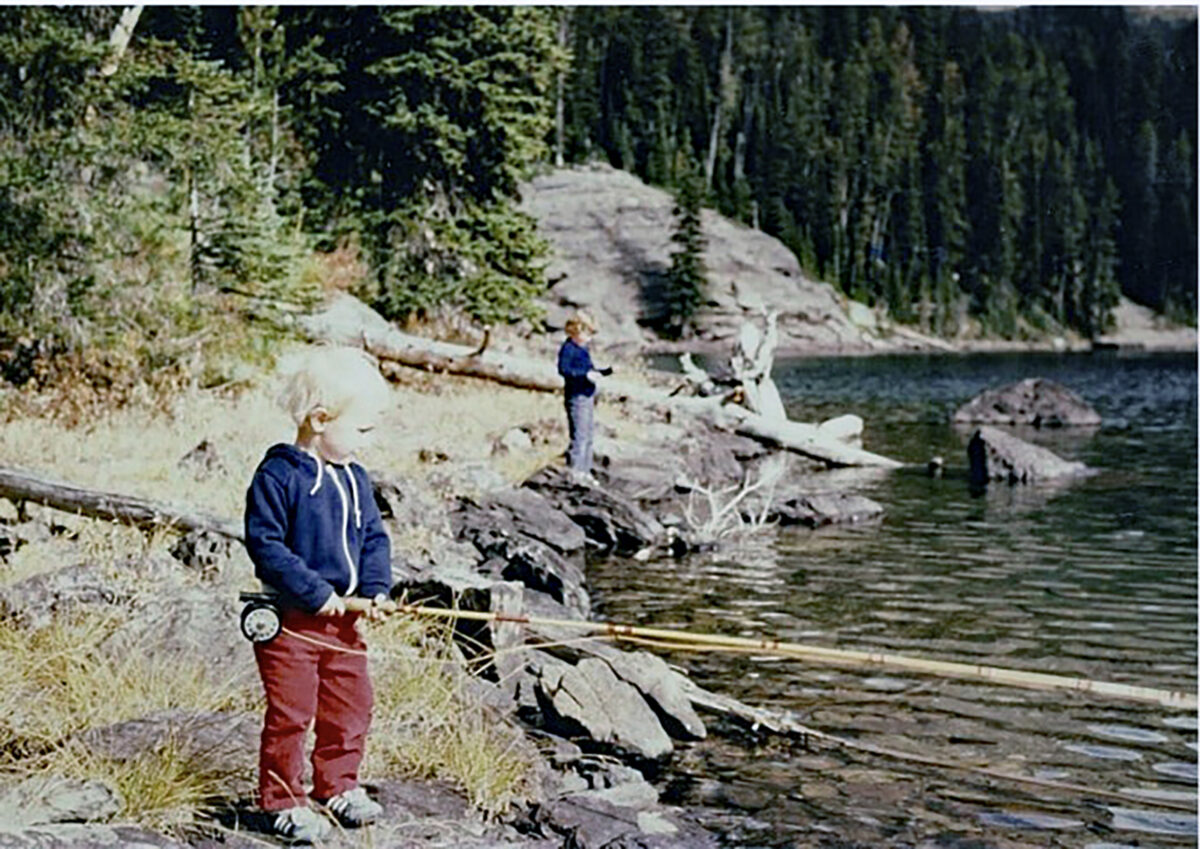

As a young boy, Lamar spent hours roaming in the Smith Creek swamp area where his backyard seemed endless and borderless, with only field and forest between him and the Bob Marshall Wilderness. His parents gave him full reign and encouraged his curiosity and exploration of the great outdoors.

His days were spent wandering with his golden retriever, led by his fascination with the natural world and all it offered — from the tiny spider crawling on a wisp of grass to the lofty Swan Mountains that formed a gigantic headboard to his playground. He was a bit of a wild child immersed among wild things. Lamar often observed signs and sounds of the animals who live here, along with an occasional close encounter. He remembers one sixth-sense experience when he says, “I felt the hair on my neck stand up.” He turned to look behind him and saw a mountain lion crouched just 20 yards away. The lion darted into the brush and Lamar made a hasty return home, opting to crawl along through a tangle of towering grass rather than retrace his steps in the direction where the lion had disappeared. Undaunted, he continued to head out his back door each day to explore this fascinating playground. Not because he hadn’t been afraid, but probably because fear is often akin to awe.

He says he began hunting when he was 12, “which is how I cut my teeth on tracking and trailing.” He also developed a passion for shed hunting (collecting naturally shed antlers from ungulates). Both activities lured him deeper into the wild and solidified his connection with the natural world.

Those experiences helped shape an appreciation and love for the animals and the land along with a desire to fight and conserve his homeland, part of the western portion of the Crown of the Continent, which is considered one of the last remaining wild and intact landscapes in North America.

This lifeline to the Swan Valley remained unbroken while he earned a bachelor of science degree in wildlife biology nearby at the University of Montana and found his dream summer job as a wilderness ranger in the Mission Mountain Wilderness. He said, “I found myself daydreaming about the Missions.” After college his goal was simple — he wanted to work outside. His work as a wilderness ranger was seasonal, so he began to piece together a way to keep working in the Mission Mountains and to live in the Swan Valley.

He helped build houses and cobbled together contract work in wildlife biology, completing snow track surveys and fisher, owl, woodpecker and waterfowl surveys. In 2012, he became involved with the Rare Carnivore Project monitoring the existence and distribution of rare carnivores in the Swan Valley, which include Canada lynx, fisher, marten, and wolverine.

In 2014, he finally settled into a year-round, full-time job when he became the conservation director of Swan Ecosystem Center, a nonprofit community-based group organized to work for the sustainable use and care of the land.

His work included a seven-year project on the Swan River National Wildlife Refuge, one of the largest wetland restoration projects in Montana to date. The project included mapping (and walking) the entire 1,979 acres of wetland. It was predictably wet, but challenges also included the tangle of reed canary grass, razor-sharp hawthorn and an occasional close encounter with a bear, hidden by the deep underbrush. It all came with the job — and the territory. A territory that he helped return to its original state. “It really improved a lot of really fantastic wildlife habitat for waterfowl and other wetland-related wildlife,” Lamar said.

In 2016, the Swan Ecosystem Center merged with another Swan Valley community nonprofit organization, Northwest Connections, to form Swan Valley Connections. Headquartered at the Condon Work Center, the newly formed SVC continued their focus on conservation, education and stewardship, through partnerships with U.S. Forest Service (USFS), other agencies, and private landowners. With the staffing and mission of both organizations under one umbrella, Lamar recently became managing director of the conservation programs and operations.

Lamar’s personal values align with those of the SVC, whose mission is to inspire conservation and expand stewardship in the Swan Valley and beyond. He explained, “I really value helping connect people with the outdoors, providing opportunities for learning, doing good conservation and stewardship work on private and public lands in the Swan Valley, and hopefully inspiring others to care for this special place as well.”

This merger, along with his continuing outdoor education, broadened his experience and views of the place where he grew up. In 2014, he took a course with CyberTracker, an internationally acclaimed organization established to restore and grow trackers worldwide, to preserve a primitive skill that was being replaced by technology. “Tracking teaches observation. I love that about it,” Lamar said. “It blew my mind because I saw things that I didn’t see before … It opened a whole new world.”

Having received his Wildlife Tracks and Sign Specialist certification, Lamar now teaches tracking and trailing courses offered at SVC throughout the year, from a one-day class to a week-long class that offers the option of college credits and a CyberTracker Certification.

Basic tracking skills include identifying characteristics such as species identification, straddle length, stride width, gait, (walk, bound, lope or other) habitat and interpretation of behaviors. Students are guided to observe other signs that might help identify the animals such as forage, scat, scratches, and rubbings. Like detectives, they look for clues to help them solve the mystery of a track discovered in snow or soil.

With experience and practice, a person can learn to identify chase scenes and kill scenes — solving forensic mysteries in the natural world. One of Lamar’s favorite stories occurred during the rare carnivore project on the Swan front, east of Seeley Lake. He was snowmobiling up a road with his work partner, Mike Mayernik, when the duo spotted a fresh kill. Coyote and wolverine tracks surrounded the partially consumed carcass of a mule deer. They decided to backtrack the scene to learn more about the incident. Several hundred yards up a steep ridge they found tracks that revealed where the yearling buck had come bounding (known as pronking) out of a clump of trees. Right alongside his tracks were the tracks of a wolverine. And then the wolverine tracks ended. The wolverine seemed to disappear into thin air.

They followed the deer tracks and noticed a tuft of hair followed by larger clumps of hair and the story began to form in Lamar’s head. He explained, “The tracks of the mule deer became so erratic that I could almost envision the deer bucking wildly, trying to rid itself of the wolverine riding on its back, much like a bronco at a rodeo trying to lose the cowboy.” More clues appeared as they continued down the slope — blood spots and then a “gushing blood trail to follow.” They performed a necropsy on the deer and discovered a bite mark on the spine in the lower neck, which was likely the fatal blow delivered to the deer by the wolverine. They found wolverine hair near the kill site (likely loosened when the wolverine shook off) which allowed them to identify it as a female wolverine known as F5, who had been first detected near Lincoln.

Lamar’s tracking and trailing skills proved valuable when he became involved in the monitoring project in 2012 to establish a baseline for rare forest carnivores, focusing on Canada lynx, fisher and wolverine. The Southwestern Crown of the Continent (Swan Valley is on the western border) was selected as the first of 10 project areas that was awarded funding under the federal Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program (CFLRP) to assess positive or negative ecological, social and economic effects of restoration projects implemented under the program. This baseline monitoring occurred from 2012 to 2016 and was followed by a subsequent monitoring project from 2021 to 2022, collaborating with the USFS, Bureau of Land Management (BLM), the Blackfoot Challenge, University of Montana, and the Nature Conservancy.

Monitoring included using non-invasive methods like snow track surveys and DNA collection through backtracking, hair snares and bait stations. By collecting genetic samples, lab analysis can identify unique individuals and accurately determine the number of different animals surveyed. The snow track surveys were conducted annually across 1,200 miles of terrain, utilizing an average of 139 bait stations. Lamar says tracking and trailing “blends science and imagination.” To the trained eye, these methods provided information about behaviors that help piece together the stories of wildlife.

The biggest surprise was probably the number of wolverines. Lamar says before they started, they didn’t have a clue as to how many wolverines they would find. He says he would have guessed there were two to five of the elusive wolverines roaming the survey area. At the completion of the survey project across the 1.5 million-acre Southwestern Crown, they identified 61 unique wolverines (32 males and 29 females) with 55 of them standing out as new entries to the regional wildlife databases. They also discovered that, in addition to the American pine marten, there were Pacific pine martens in the region. The survey identified 109 unique Canada lynx with 95 new entries to the regional databases. No fishers were found during this intensive monitoring effort.

Collaborations with federal partners and other stakeholders provide additional expertise capacity and funding for the surveying projects. Most recently, SVC partnered with the USFS’ Rocky Mountain Research Station (RMRS) in Fort Collins, Colo., as well as the BLM to launch a new research effort to analyze lynx habitat in 15- to 20-year-old wildfire areas, prompted by data that found large concentrations of lynx in similar environments. As it turns out, there is also an abundance of snowshoe hares, which make up the majority share of a lynx’s diet.

Remote cameras at bait stations capture live and still photos of the animals and their behaviors, adding a valuable tool for understanding wildlife. There is an element of entertainment in the gymnastics of a wolverine, fox or lynx trying to wrangle bait hung in a tree, in the dance-like moves of a bear while visiting a rub tree, and the bark-like screech of the highly vocal lynx. Lamar also runs about a dozen cameras on this own time for fun, without using bait to lure animals to where the cameras are mounted.

Lamar’s other projects have included fuels reduction aimed at improving forest health, and working with the group Swan Valley Bear Resources to reduce conflicts between humans and bears. His time in the field does not end with his work day. He says, “On my days off, I’m always outside recreating, exploring, and appreciating the wild and remarkable Swan Valley.” He is usually with his wife, Sara, and golden retriever, Griz. It seems poetic that he met Sara at SVC after she was hired for an internship in 2014; but for Lamar, it also follows a logical narrative arc. The couple not only shares the same mission at work, but also a love for the outdoors and all it offers, including, hiking, fly fishing, hunting, backpacking, checking game cameras, and cross-country skiing.

Lamar will probably never leave the Swan Valley, which might sound limiting to some. But with his ability and desire to roam, to explore and study millions of acres of varied terrain in constant flux, there will always be new paths to take — and paths he might like to retrace. With all its mystery and magic, the wild Swan will always hold the promise of more adventure and discoveries for this native son.