EPA Issues Long-awaited Decision on CFAC Superfund Cleanup Plan

Federal regulators on Friday afternoon published a record of decision approving a cleanup remedy for the contaminated aluminum plant property near the Flathead River. Federal and state regulators estimate that the actual cleanup activities, once initiated, will take two to four years to complete.

By Tristan Scott

After spending much of the past year trying to allay the concerns of residents living near a contaminated former industrial property near the Flathead River, federal regulators for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) on Friday afternoon issued a long-awaited record of decision (ROD) finalizing its plan to remediate the Columbia Falls Aluminum Company (CFAC) Superfund site.

The 432-page document is a key milestone in the years-long environmental remediation investigation and provides a detailed account of the EPA’s plan to contain pockets of toxic waste buried on the sprawling property at the base of Teakettle Mountain. Although the former industrial site has been dormant since 2009, a recent wave of community concern has centered on the EPA’s proposal to contain rather than remove the environmental hazards; specifically, groundwater in the plume core that contains concentrations of cyanide, fluoride and arsenic in dangerous concentrations, posing risk to future residential drinking water users.

EPA officials sought to address those concerns at a series of community engagement sessions in 2024, as well as in an exhaustive section of the ROD, which is divided into three parts. The document’s final section is dedicated to addressing more than 800 public comments, with many of them focused on the waste-in-place proposal. While the property’s owners and its neighbors hadn’t yet had time to digest the ROD on Friday afternoon, the document makes it clear that the EPA’s proposed remedy remains largely intact.

“It’s going to be a total weekend read,” John Stroiazzo, the project manager for CFAC, which is owned by Swiss commodities giant Glencore, said when reached late Friday afternoon. “It’s hundreds of pages.”

Matthew Dorrington, the EPA’s project manager for the CFAC Superfund site, said the ROD largely supports the agency’s proposed plan, with one notable exception to the type of lining it intends to use to contain waste in a reservoir overflow ditch.

“To me, those concerns [about containing rather than removing the waste] really bore the full brunt of all of our engagement and dialog,” Dorrington said. “I do not want to diminish those concerns, which the ROD addresses in detail. But at the end of the day the proposed plan is very much reflected in the record of decision.”

Dorrington characterized the ROD as a midpoint in the cleanup saga, marking the fifth step in the nine-step Superfund process, with ongoing community involvement throughout.

Key components of the remedy include:

- Slurry walls designed to isolate waste and prevent contaminant migration.

- Improved waste covers to reduce exposure and infiltration.

- An on-site landfill to safely encapsulate contaminants without off-site disposal.

- Long-term monitoring to ensure the effectiveness of the remedy over time.

The ROD marks a transition from the investigative phase to the cleanup implementation stage at the site, establishing a framework for future cleanup actions to protect the Flathead River and reduce risks to the Columbia Falls community and environment, according to officials.

EPA will now work with the Montana Department of Environmental Quality to finalize a consent decree with the responsible parties — Glencore and the Atlantic Richfield Co. (ARCO), a subsidiary of the oil and gas behemoth BP America — to ensure cleanup actions proceed as planned. The consent decree will include a comprehensive statement of work and will be open for public comment before finalizing. EPA and DEQ estimate that the actual cleanup activities, once initiated, will take two to four years to complete.

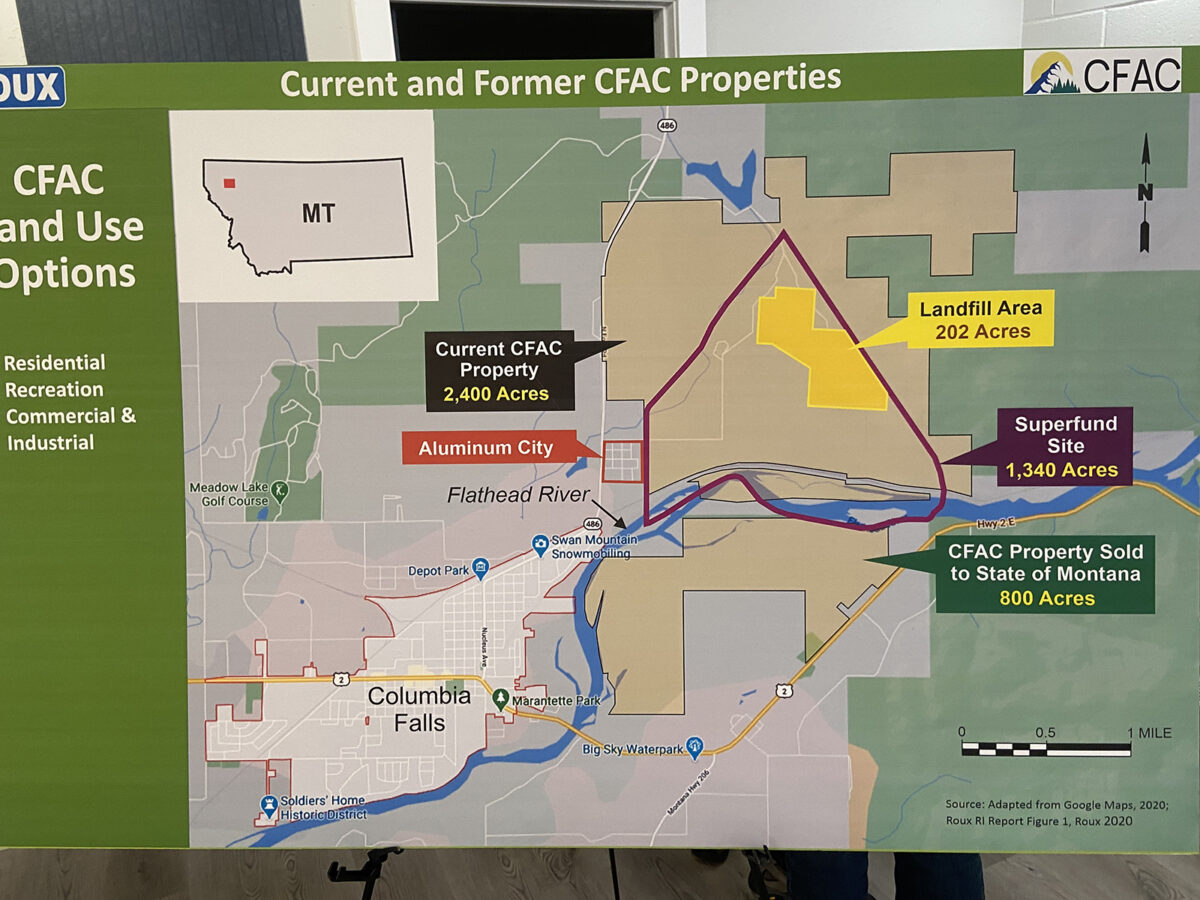

EPA released its proposed cleanup plan for the 2,400-acre CFAC property last year to little fanfare. Community interest erupted last spring, however, when Glencore publicly announced plans to sell most of its acreage to Ruis Construction owner Mick Ruis for residential and commercial use. While the terms of the sale are confidential, the deal is contingent on EPA finalizing the details of its proposed cleanup plan by issuing the ROD.

According to Stroiazzo, nothing in the ROD should affect the pending land deal.

“The sale is predicated on the proposed plan,” Stroiazzo said Friday afternoon. “If the proposed plan does not change materially than the sale goes ahead. If we’re happy and he’s happy and the ROD is based on the proposed plan, then I don’t foresee any issues there.”

The central focus of the cleanup plan is Decision Unit 1 (DU1), which comprises the former CFAC plant’s west landfill and its wet scrubber sludge pond, where experts have pinpointed the highest concentrations of contaminants. Most concerning, experts say, is that the groundwater plume underneath the unit is laced with poisonous amounts of cyanide, arsenic and fluoride, which are the byproducts of the aluminum smelting process that occurred for more than a half-century. That process began by dissolving aluminum oxide in a bath of molten cryolite, which was contained inside brick-lined cells, or pots. The bricks were used to insulate the pots from the temperature conversion process and, when they failed, needed to be disposed of and replaced.

Even though the landfills are capped, they have been releasing contaminants into the groundwater whenever seasonal high-water levels touch the buried waste, migrating toward the Flathead River, where concentrations of metals in the seeps along the river are relatively low. While some DEQ standards for aquatic life are exceeded, “there is no contamination above background values in the Flathead River,” according to EPA.

Dorrington previously explained the toxicity of the contaminants in the groundwater plume degrades as they migrate toward the river so that, even without treatment, they are below the state’s standards for human health.

“But they still exceed aquatic life toxicity criteria. That’s what’s driving the need for the cleanup,” he told the Beacon last summer.

Dorrington said there have been no documented impacts to fish or other aquatic organisms, and water quality in the river meets state and federal standards. The feasibility study’s analysis shows that the proposed remedy will reduce concentrations to acceptable levels in the seeps without removing the landfilled wastes, but the cleanup plan still calls for constructing a semi-fluid sub-surface barrier around DU1 to contain the waste. Called a slurry wall, the barrier would stretch 3,000 to 4,000 feet in length, wrapping around the perimeter of DU1 and filling a trench 120 feet deep before tying into the aquitard, a geologic formation with a low rate of permeability that would form the fourth wall of a containment cell designed to hold the reservoir of contaminated groundwater at the source.

“That’s the key right there. Where the slurry wall ties in with the aquitard,” Dorrington said. “But even if it fails; even if there were cracks or fissures, it wouldn’t be like a dam breach, and there would be backup protocol in place.”

That backup protocol includes installing eight pairs of extraction/monitoring wells (one within and one outside of the slurry wall) downgradient of the wet scrubber sludge pond, with another series of monitoring wells downgradient of the slurry wall. The remediation plan also calls for constructing a groundwater treatment facility.

“All of our experts are quite confident that this will work quite well,” Stroiazzo said.

The EPA did evaluate the cost of off-site disposal, estimating it as ranging from $625 million to $1.4 billion, compared to the $57.5 million cost of the preferred alternative. The agency also evaluated the logistics of off-site disposal, including excavating about 1.2 million cubic yards of hazardous waste from the landfills, which would need to be dewatered and carted off site to the nearest Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) landfill in Arlington, Ore., nearly 500 miles away. The process would require 60,000 truckloads or rail containers passing through 30 neighboring communities on the way to the Oregon landfill, including Spokane, Wash., and the Tri-Cities, amounting to 70 trucks or trains per day over the course of four or five years “with associated noise, dust, congestion, traffic issues, and delays from railroad crossings.”

In a press release announcing the ROD’s publication, EPA Regional Administrator K.C. Becker hailed it as “a crucial step in finalizing a comprehensive set of cleanup actions that will protect the health of the community and the environment.”

“In partnership with Montana DEQ and the Columbia Falls community leaders, we have worked to ensure public participation and transparency throughout the process,” Becker stated. “We are moving forward now to get the cleanup underway, protect the Flathead River, and move towards a safer, healthier future for everyone who calls the Columbia Falls area home.”

The Montana Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) also endorsed the cleanup ROD.

“DEQ’s highest priority, for any Superfund site in Montana, is that the selected remedy be protective of human health and the environment,” according to a prepared statement from DEQ Director Sonja Nowakowski. “We are confident that the plan announced today will meet those criteria, and DEQ will work with stakeholders and the EPA to ensure that the cleanup is successfully implemented.”

The EPA emphasized that it provided the community with a technical assistance advisor through the Technical Assistance Services for Communities program to help residents better understand the technical issues and documents associated with the Proposed Plan.

The Record of Decision and supporting documents are available for public access at the ImagineIF Library, 130 Sixth St. W., Columbia Falls, and on the EPA’s CFAC Superfund Site webpage. The public can also find the ROD and related materials on the EPA’s CFAC Superfund Site webpage.