On winter evenings at dusk, a 2012 Prinoth Bison groomer fires up on Canyon Creek Road north of Columbia Falls and begins combing corduroy into the snow, crawling up the mountain at a maximum speed of 7 miles per hour. For the next six to seven hours, grooming operators cover as much of the 85-mile trail system as they can on a multiuse route that extends to the Whitefish Mountain Resort boundary and beyond, stretching west all the way to Olney.

The Bison is one of three machines the Flathead Snowmobile Association (FSA) uses to groom more than 200 miles of trails across the Flathead Valley for snowmobilers, Nordic skiers and dogsledders. A second 1990s-era groomer is responsible for the Crane Mountain trail system near Bigfork while a third maintains the network of forest roads scoring Desert Mountain in Martin City.

“They’re out there typically by themselves,” FSA President Amanda Berlinger said. “They’re trucking right along but it’s cold, it’s slow, and it’s dangerous. It’s the middle of the night in the middle of a snowstorm — in the middle of some place that doesn’t have cell service.”

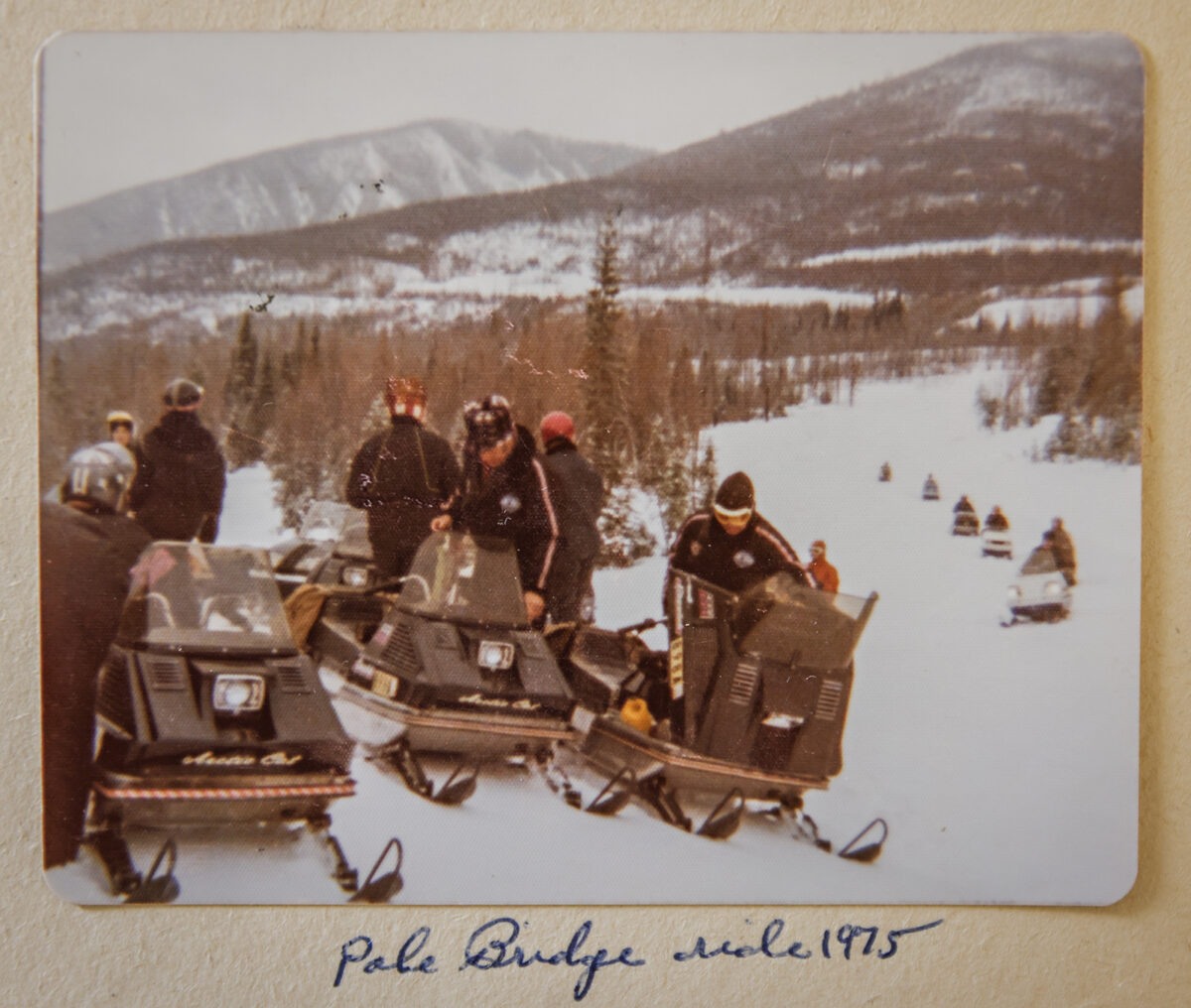

After forming in 1971 as a social club for snowmobilers, the FSA started grooming trail systems in the 1980s and began partnering with state and federal agencies for maintenance. The organization has a handful of grooming operators on the payroll, and the association has 282 members this year. Volunteers work on trail projects in the summer and repair the grooming machines, which require specialized mechanical skills and expensive and elusive part replacements.

But even as snowmobiling gains popularity, Berlinger says the club’s membership fluctuates each year, while it’s become increasingly difficult to recruit younger snowmobilers to help out with projects.

“It’s a struggle to engage younger members,” Berlinger said. “Our volunteer force is very hands-on and we’re working on giant specialized machines — there’s a shortage of people who will work on things like that and it’s increasingly hard to find someone who will work on them out of the kindness of their hearts.”

Since Berlinger took the helm as the snowmobile association’s president this year, she’s been working hard to engage members and potential members through social media. She’s also upgrading technology and plans to equip the groomers with Starlink satellite internet. In September, she resurrected the Keller Ranch Grass Drags, which was historically held as an annual, off-season snowmobile race that was last hosted in the 1990s.

Maintaining a good relationship with state and federal agencies has also been key for the snowmobile association to continue grooming operations, Berlinger said, and the organization is powered by three Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks (FWP) grant programs. The Recreational Trails Program (RTP) is funded through the Federal Highway Administration; the Trail Stewardship Program (TSP) uses state recreation fees and the light vehicle registration fee; and the Montana Snowmobile Program is supported by snowmobile registration, grooming fees and gas tax refunds. Each grant involves strict rules, and funding must be used for specific projects.

Upfront capital is required for the federal reimbursement program, which Berlinger describes as a heavy financial lift for a volunteer nonprofit.

FSA also operates under land use agreements with the Flathead National Forest and the Stillwater Department of Natural Resources and Conservation (DNRC) to maintain grants.

Berlinger describes the work she and other volunteers put into the snowmobile as labor intensive while there’s also a tall stack of paperwork involved to continue operating.

“The struggle is real — we have to operate under strict adherence under both federal and state adherence,” Berlinger said.

While FSA has partnered with land use agencies since the 1970s to establish the Flathead Valley’s first designated snowmobile routes, the organization has also gradually added more partnerships with other nonprofits and volunteer organizations to its roster in recent years.

The 2010s defined an era of safety promotion as the association bolstered its relationship with North Valley Search and Rescue, through which volunteers regularly use snowmobiles for winter missions.

“We are a huge partner with search and rescue,” Berlinger said. “One of our trails comes down to Flower Point, which is on the backside of Big Mountain where we’ve had fatalities and lost skiers. Search and rescue can directly get there.”

In the last decade, the snowmobile association has also strengthened its relationship with the Flathead Avalanche Center, which hosts motorized avalanche courses and has worked to reach snowmobilers in addition to backcountry skiers, who have traditionally been more receptive to engagement.

“How can you not love an organization that only wants you to come home safe?” Berlinger said. “They only care for us and everything we do.”

The Flathead Avalanche Center’s nonprofit arm, Friends of the Flathead Avalanche Center (FOFAC), has in recent years provided more motorized avalanche courses as demand grows.

That demand has grown dramatically in the last seven years when FSA member Mark Smolen formed the club’s own nonprofit arm, Friends of the Flathead Snowmobile Association, so they could apply for safety grants.

Each year, the friends group applies for the Flathead Electric Cooperative Roundup for Safety grant to provide avalanche course reimbursements and incentivize more motorized users to take classes.

“We fund most, if not all, of the motorized components for training,” Smolen said.

Smolen said in addition to the reimbursement perk, there is also typically an uptick in demand for avalanche education following avalanche fatalities, which was the case when FSA member Dave Cano was killed in in the northern Swan Range in 2021.

While Cano and his riding partners were experienced and educated, Smolen said the story served as a “wakeup call” for some users.

FOFAC Director Jenny Cloutier said she’s recently noticed a significant uptick in motorized course participation compared to when the Flathead Avalanche Center launched in 2014, which she attributes to the reimbursement program.

“For years, we have been trying to increase motorized participation in our courses,” Cloutier said. “It’s been pivotal — we were at the point with motorized courses where we were on the fence of canceling.”

Cloutier has also noticed more snowmobilers engaging on the Flathead Avalanche Center’s website by submitting public observations to inform forecasters and other recreationists of avalanche conditions.

“We were trying to crack this nut for so long and their help was the thing we needed,” Cloutier said. “Their partnership has gotten way more education.”

But as partnerships grow and as Berlinger and FSA volunteers continue building relationships to ensure there is access on state and federal lands, she sometimes worries the decline in engagement could jeopardize snowmobile access.

Dave Covill, who served as the FSA president for a decade before passing the torch to Berlinger, said the group’s members have been working to educate the public about the organization’s mission.

“In general, a lot of people don’t have a very good idea of what we do, and we’re trying to remedy that with education and posting on Facebook and Instagram and trying to get the word out,” Covill said. “It’s one of those things where snowmobilers show up at trailheads and they think grooming is just magically provided.”

FSA Vice President Brian Weber, too, says much of the community doesn’t realize the snowmobile association is responsible for trail maintenance.

“That’s what I hear over and over — everyone just thinks it happens,” Weber said.

Historically, Berlinger says FSA members have been reluctant to ask for help from volunteers, but leaders are actively working to grow the member base and are seeking more resources.

“There’s a culture we’re trying to change of not necessarily asking for help — so we’re asking for help,” Berlinger said. “The thing about motorized access is if we don’t maintain it and we don’t use it we will lose it. And if we cannot maintain it because we don’t have the volunteer commitment and we can’t keep it alive, there’s a strong chance we won’t get it next year.”