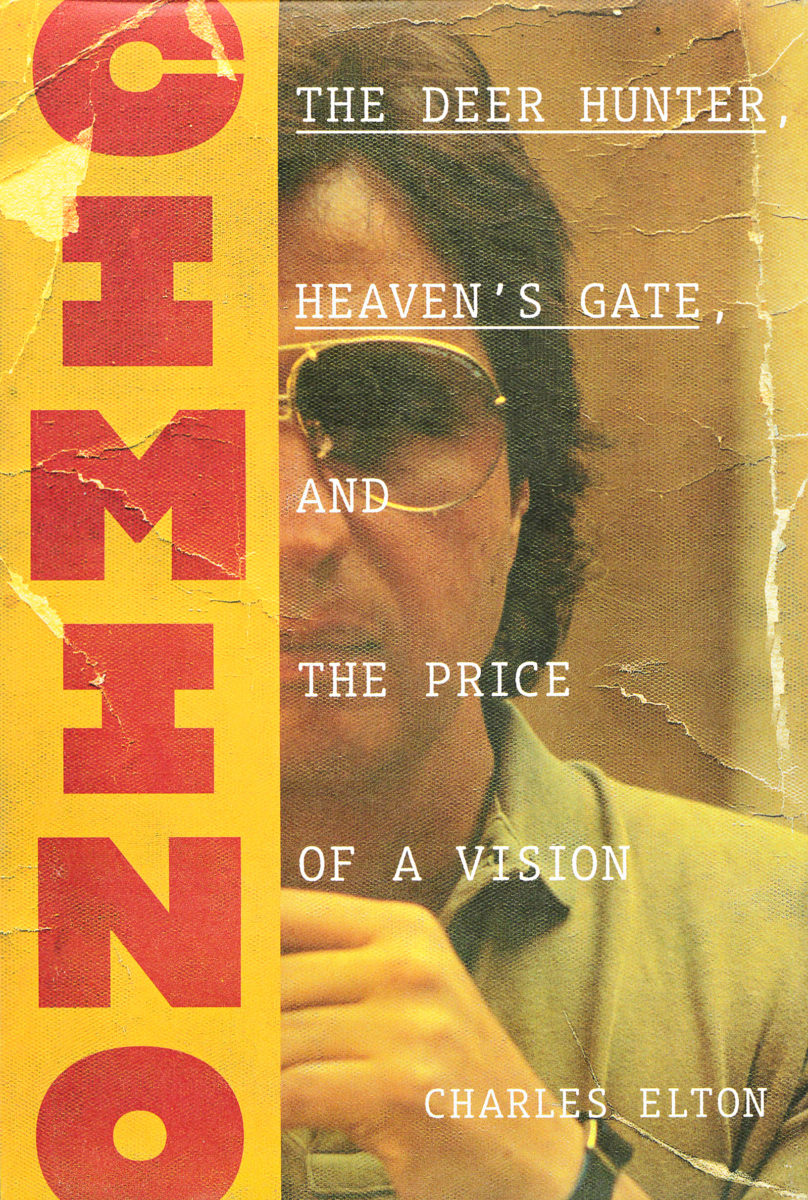

Book Examines Complex Life and Legacy of Director Michael Cimino, and Polarizing Film ‘Heaven’s Gate’

Charles Elton’s book "Cimino: The Deer Hunter, Heaven’s Gate, and the Price of a Vision," was published earlier this year

By Mike Kordenbrock

On October 7, 2019, the London-based television producer and author Charles Elton checked into the Fairbridge Inn and Suites and Outlaw Convention Center in search of clues about an enigmatic Hollywood director who in early October 40 years earlier had wrapped up filming a movie he envisioned as his next masterpiece.

The director had stayed at the same hotel, then called the Outlaw Inn, and he had been surrounded by members of a cast and crew for a production that included Kris Kristofferson, Jeff Bridges, Christopher Walken, Isabelle Huppert, John Hurt and Sam Waterston.

For longtime Kalispell residents, it may be obvious at this point who Elton was on the trail of, and what had brought all of these celebrities to a remote northwest Montana town in the late 1970s for seven months of filming that the chamber of commerce at the time estimated brought nearly $14 million into the local economy.

Elton’s trip to Kalispell was part of the reporting work he put into his most recent book, a biography of the director Michael Cimino called “Cimino: The Deer Hunter, Heaven’s Gate, and the Price of a Vision.”

“Heaven’s Gate” was Cimino’s third movie, and his next film after his award-winning 1978 Vietnam War movie “The Deer Hunter.” The movie was based on the Johnson County War, a violent chapter in Wyoming history in which cattle barons in the 1890s hired a small army of men and directed them to Johnson County with the intention to kill 70 residents who were suspected of being cattle rustlers.

In Cimino’s adaptation, Kristofferson and Hurt play Harvard University graduates and friends who are on opposite sides of the conflict, with Kristofferson serving as the marshal for Johnson County, and Hurt aligned with the Stockgrowers Association led by the cold-blooded Frank Canton as played by Sam Waterston. Kristofferson is in love with a brothel madame played by the French actress Isabelle Huppert, whose character is on a kill list because she accepts cattle in lieu of cash payments. Walken, who kills rustlers for the Stockgrowers Association, is also in love with Huppert, and eventually finds himself at odds with the Stockgrowers and their bloody mission which primarily targets European immigrants settled on small pieces of land.

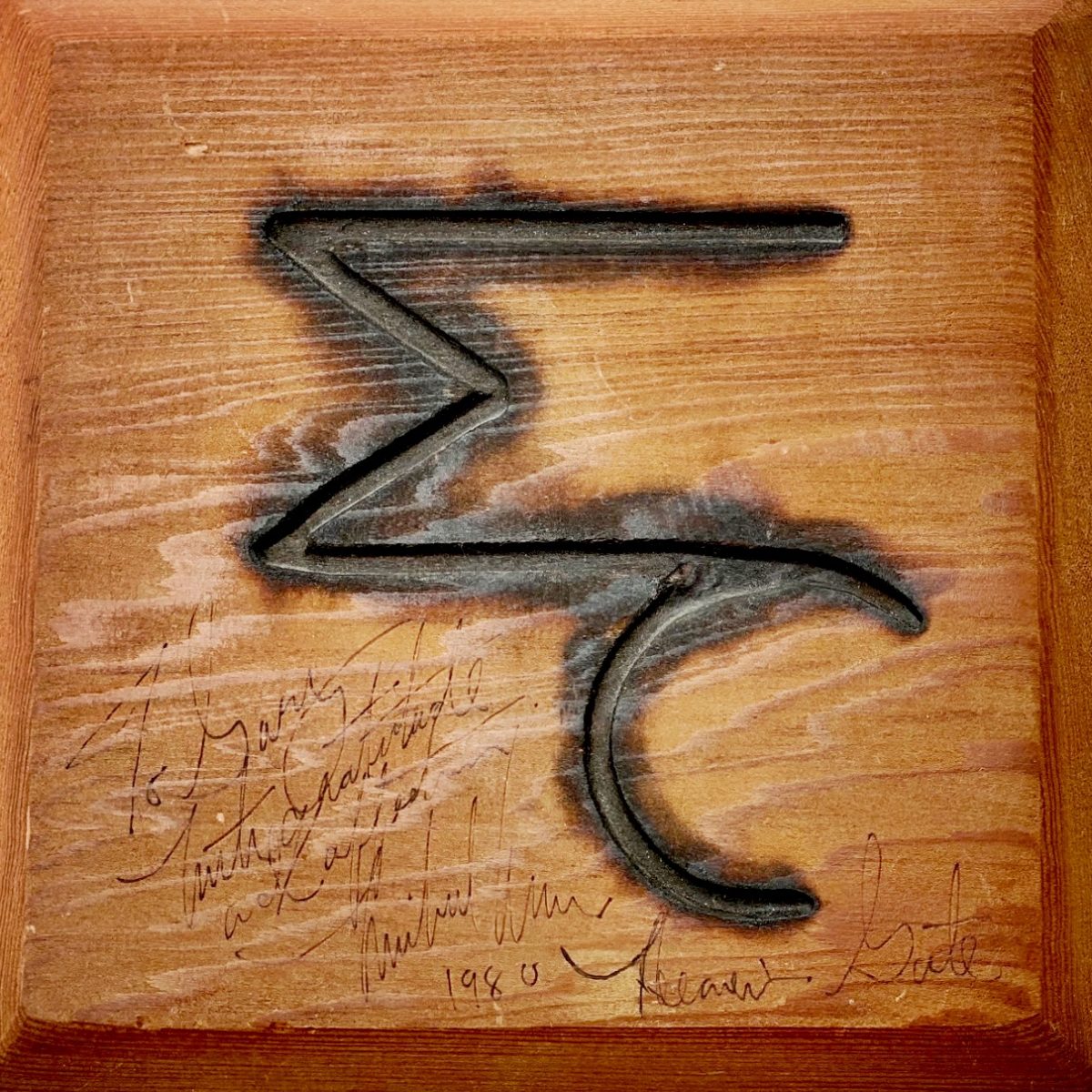

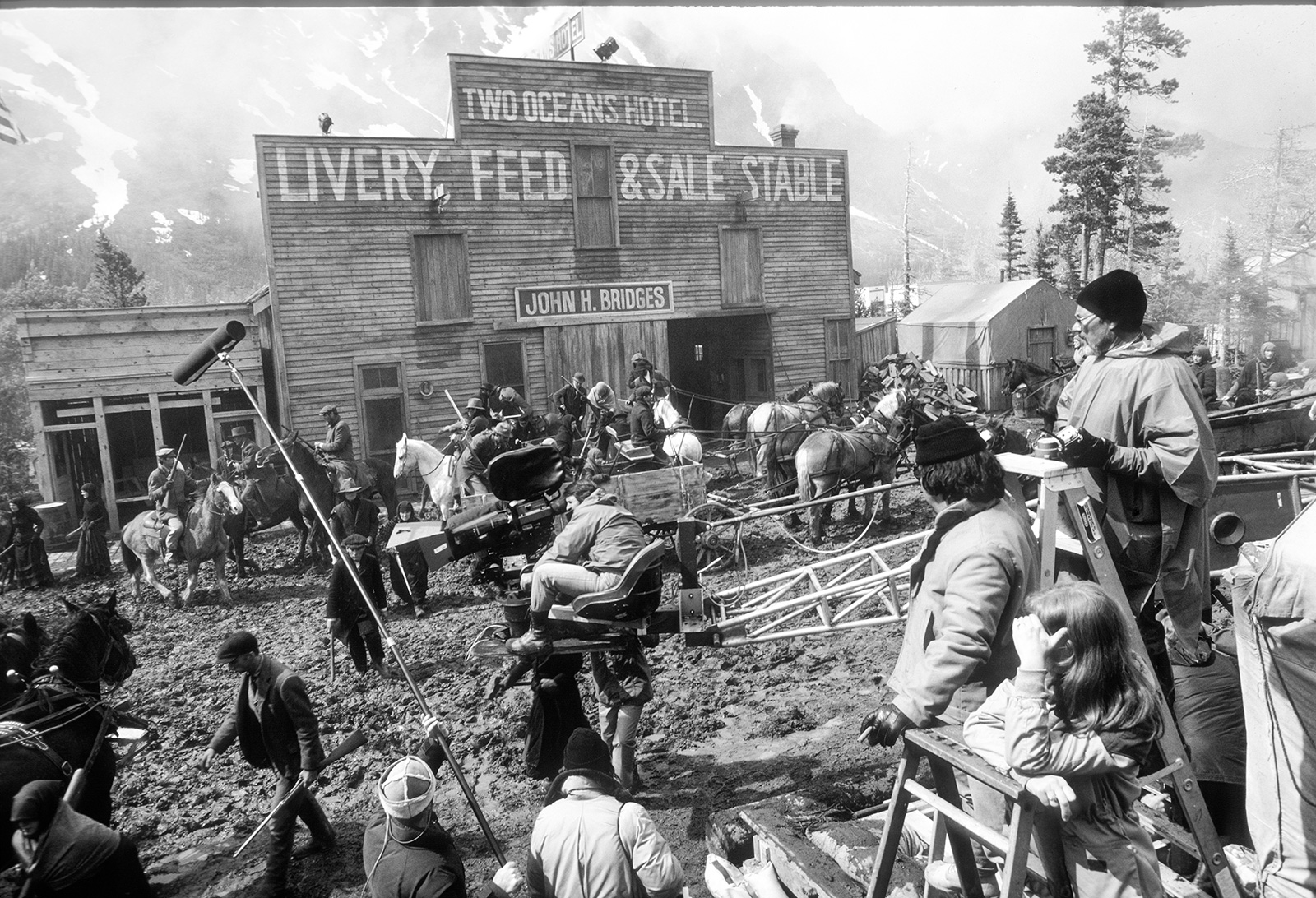

The cast and crew of the movie were based out of Kalispell, but filming was done primarily along Two Medicine Lake in East Glacier Park, where a set for the fictional town of Sweetwater was constructed.

Michael Cimino’s “Heaven’s Gate,” was considered a disaster, to the point that the phrase “Michael Cimino’s movie ‘Heaven’s Gate,’ was considered a disaster” probably classifies as a cliché, and the well-worn narrative surrounding the film has become a cautionary tale about what can happen when a movie goes creatively and financially off the rails. Cimino ultimately took the fall for the end of a golden era for Hollywood directors when studios were more apt to finance unconventional projects helmed by visionary auteur directors. Cimino has also been blamed for the demise of United Artists, the studio that spent more than $40 million on a movie initially budgeted for $11.5 million, and then only made a few million dollars back at the box office in the U.S. Elton makes the case that that popular narrative is about as accurate as the invented story of George Washington cutting down a cherry tree.

On its initial release, “Heaven’s Gate” was a nearly four-hour film that was met with what Elton calls in his book “probably the most devastating reviews ever published for a movie.” The movie wasn’t tested in front audiences before release, and sound editing problems in a critical scene made the plot hard for audiences to follow, and Cimino and his cinematographer tinted the film “with a kind of yellow glow” that was supposed to give an antique look, but instead “it seemed as if the picture was shrouded in nicotine smoke,” Elton writes. The film was pulled from theaters and re-edited and a shorter version was released, but it did little to make a dent in financial losses. The film’s reception was devastating to Cimino who struggled afterwards, both personally and professionally, to try and recover from the experience. In the decades since, the consensus on “Heaven’s Gate” has shifted in a positive direction, with some critics calling it a masterpiece. The original long version was re-released in 2012 and helped drive the reappraisal of the movie.

But back to Elton. A novelist without an idea for another novel, Elton is also a lifelong cinephile. A friend suggested that Elton, who already knew a staggering amount about Cimino, should pursue a biography of the director.

“I thought, ‘Well, I don’t know if I can write a biography. I’ve never written one before.’ And I just began tinkering with it. And I went out to L.A. where I’d worked before, so I knew L.A. pretty well, and I just sort of began looking for a few people. And it just gradually began to kind of snowball, and after about a year of going to L.A. sometimes and writing some things down, I was obviously writing the book without me quite realizing I was writing the book,” Elton said.

Part of what made Cimino such a worthy subject for Elton was his mastery as a filmmaker.

“He was technically absolutely brilliant. He knew exactly what he wanted and he knew exactly how to get it …” Elton said. “You have to have that clear vision of what you want. And he absolutely had that.”

The book begins in 2018, two years after Cimino’s death, with Elton peering up through padlocked gates at Cimino’s home in the Hollywood Hills. Elton writes how Cimino’s home was “both a refuge and a prison after his last film in 1996,” and how “most of his friends had never been there.” The gated home, visible and tantalizingly close, but ultimately inaccessible, is representative of the challenges Elton faced in trying to understand Cimino. Over the course of the book it becomes apparent that taking Cimino’s statements at face-value can be a risky endeavor, and Elton’s efforts to get to the truth, or in some cases near the truth, lend the book a momentum that makes it feel at times like a page-turning thriller.

In one of Cimino’s most notorious lies, delivered during an interview around the release of “The Deer Hunter,” the director claimed that he enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1968 after the Tet Offensive and that although he never went to Vietnam he had been assigned to a Green Beret training unit. The journalist Tom Buckley wrote an article in response and reported that Cimino had enlisted in the Army Reserve in 1962, and was in the service for five months. He concluded of the Green Beret claim, “Cimino may have seen a couple of them in a chow line . . . but he never wore the Green Beret himself.”

In reporting out the story of “Heaven’s Gate,” Elton’s trip to Kalispell helped crystallize in Elton’s estimation that “Heaven’s Gate” is the most exciting thing to have ever happened in Kalispell. He took out an ad in the Daily Inter Lake asking for people to contact him if they were interested in talking to him for his book and was blown away by the response. He heard back from 60 people, and then narrowed his list down to 10 people to interview while he was in town. He said he’s still in touch with some of them and remains stunned at the hospitality he was shown. People brought scrapbooks and newspaper clippings.

“The book wouldn’t be nearly as good if I hadn’t gone to Kalispell,” he said.

Elton’s book documents how the excitement over the movie eventually turned into a kind of weariness and frustration locally, something the author said is in keeping with familiar patterns when it comes to movie shoots that come to a town or city. Cimino eventually ran afoul of Glacier National Park for violating some of the rules put into place to maintain the environmental integrity of the park. The park superintendent at the time, Phil Iverson, eventually pulled the movie’s permit to film in the North Fork after the Two Medicine Lake scenes were finished.

In response, Cimino and one of his closest associates, Joann Carelli, held a press conference outside the Outlaw Inn where Cimino declared “Iverson is exhibiting a total isolation from the community of northern Montana–maybe the same isolation President Nixon exhibited in the Oval Office.”

Frustration was also building among some of the extras, some of whom who were upset with conditions, their treatment and in some cases their roles in the movie. Elton writes of how after the movie left town bright yellow t-shirts declaring “I Made It Through Heaven’s Gate” started showing up on locals. Carelli made her own criticism of Kalispell, saying that “The longer you stay in a place like this, the more people seem to think you have a lot of money. After all, you’re from Hollywood, right? They really start to rip you off. It was like hold-up time without a gun.”

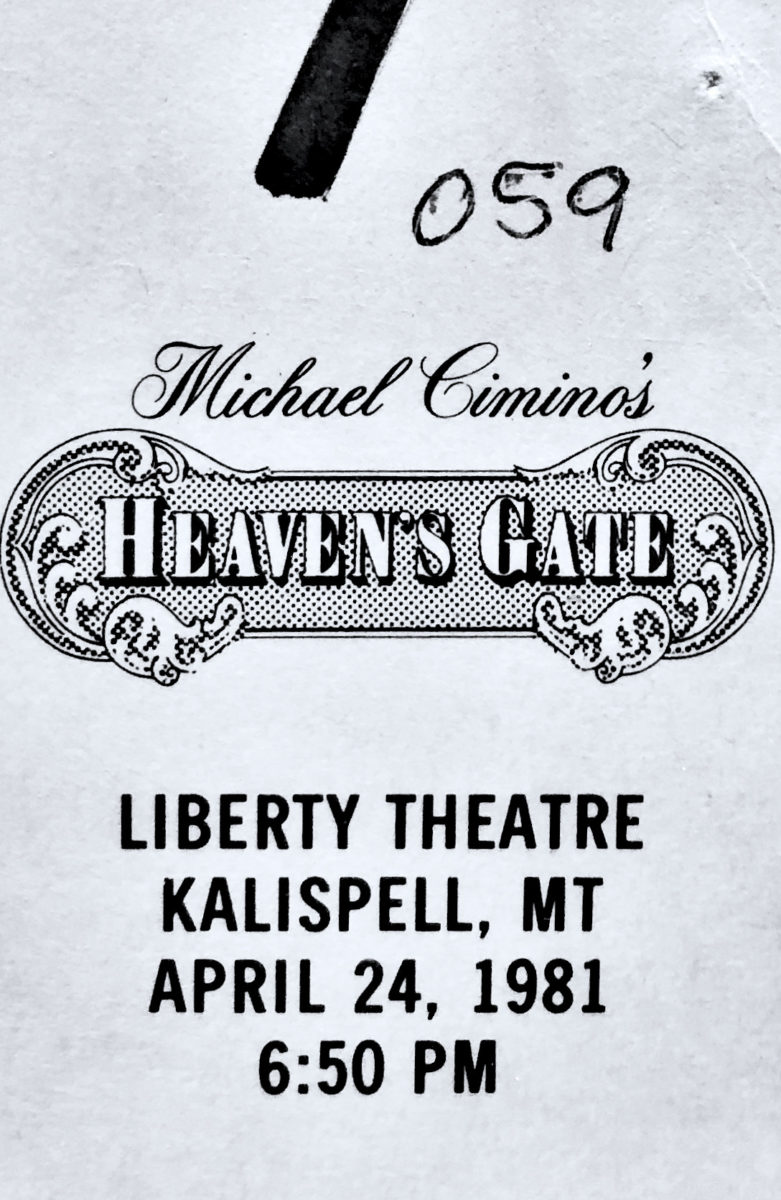

And yet, Kalispell was one of the few places where the movie was well-received upon release. Elton writes “There was only one group of people who did love it, who whooped and hollered when it was screened for them: the citizens of Kalispell, for whom Cimino organized a special screening when the short version was release.”

Elton reports in the book that 2,500 locals were employed as extras for the movie and told the Beacon that talking with some of those people, and other workers and crew members, like Cimino’s driver in Montana and his assistants, was key.

“I realized that the people who knew where the bodies were buried were the below the line people,” Elton said.

Cimino’s insistence on realizing his vision with limited efforts at diplomacy or compromise, or even truthfulness, helped alienate him from Hollywood powerbrokers after “Heaven’s Gate.” Elton describes the filming as orderly but slow, citing as an example a week of filming that produced two minutes of footage, compared to the industry standard of two minutes of footage produced out of every day of filming. The Outlaw Inn, where Elton stayed during his time in Kalispell, was not only a gathering place for locals and celebrities during filming, but it was the backdrop for a number of dramatic episodes as tensions grew between Cimino and United Artists over the movie.

At one point, a new producer, Derek Kavanagh, was brought on to try and rein Cimino in amid a ballooning budget driven by the slow pace of filming that progressed based on the satisfaction of Cimino’s ambitions for meticulously detailed, immersive scenes.

“The next day, Cimino wrote a memo to him and posted it in the lobby of the Outlaw Inn. It read ‘Derek Kavanagh is not to come to the location site. He is not to enter the editing room. He is not to speak to me at all.'”