In Northwest Montana, Private Timber is Betting the Forest on Public Access Protection

Land and wildlife managers, timber companies, hunters, and conservationists have stitched together a checkerboard of vulnerable working forests, using easements to protect private timberland from development. With a critical piece of the puzzle coming up for final land board approval, advocates say a new model of forest management is taking shape.

By Tristan Scott

On a bright October morning west of Marion, from a viewpoint along a forested county road corridor interspersed with commercial real estate signs, Neil Anderson surveyed the north slope of Dredger Ridge, a favorite walk-in elk hunting area for generations of Montanans. Widely known as the most productive public hunting ground for harvesting an elk in the region, the mixed conifer stands flanking Dredger Ridge are central pieces on a checkerboard of private timberland that’s been managed for public access for a quarter-century, despite a succession of ownership.

To Anderson, the region’s wildlife manager for Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks (FWP), it represents not only an unbroken migration boulevard for deer and elk, but also the connective lacing together a broader mosaic of protected wildlife habitat and working forests connecting Glacier National Park to the Cabinet Mountains Wilderness and the Selkirk and Coeur d’Alene mountains.

“Everything is intact. It hasn’t been chopped up,” Anderson said. “As we were driving up you saw all the ‘for sale’ signs. That could have been the future of this landscape. But by maintaining this as open space, by maintaining it as a working forest, it benefits the wildlife. It benefits the community, it benefits the timber industry, and it benefits the public because this land is now open year-round for them to access. But imagine, if you start breaking this up, that goes away. And it’s not just that ridge there, it’s everything behind it.”

“But you could see why this would be a pretty attractive view for someone buying a home,” he said, still scanning the panorama.

From where Anderson’s standing, though, the view is more complicated, even if it’s no less scenic. From his vantage, the forest canopy hides hummocks of bunch grass, forbs, and other well-inspected browse range for elk and deer, which roam a conservation easement that FWP acquired to protect 7,256 acres of timberland and wildlife habitat.

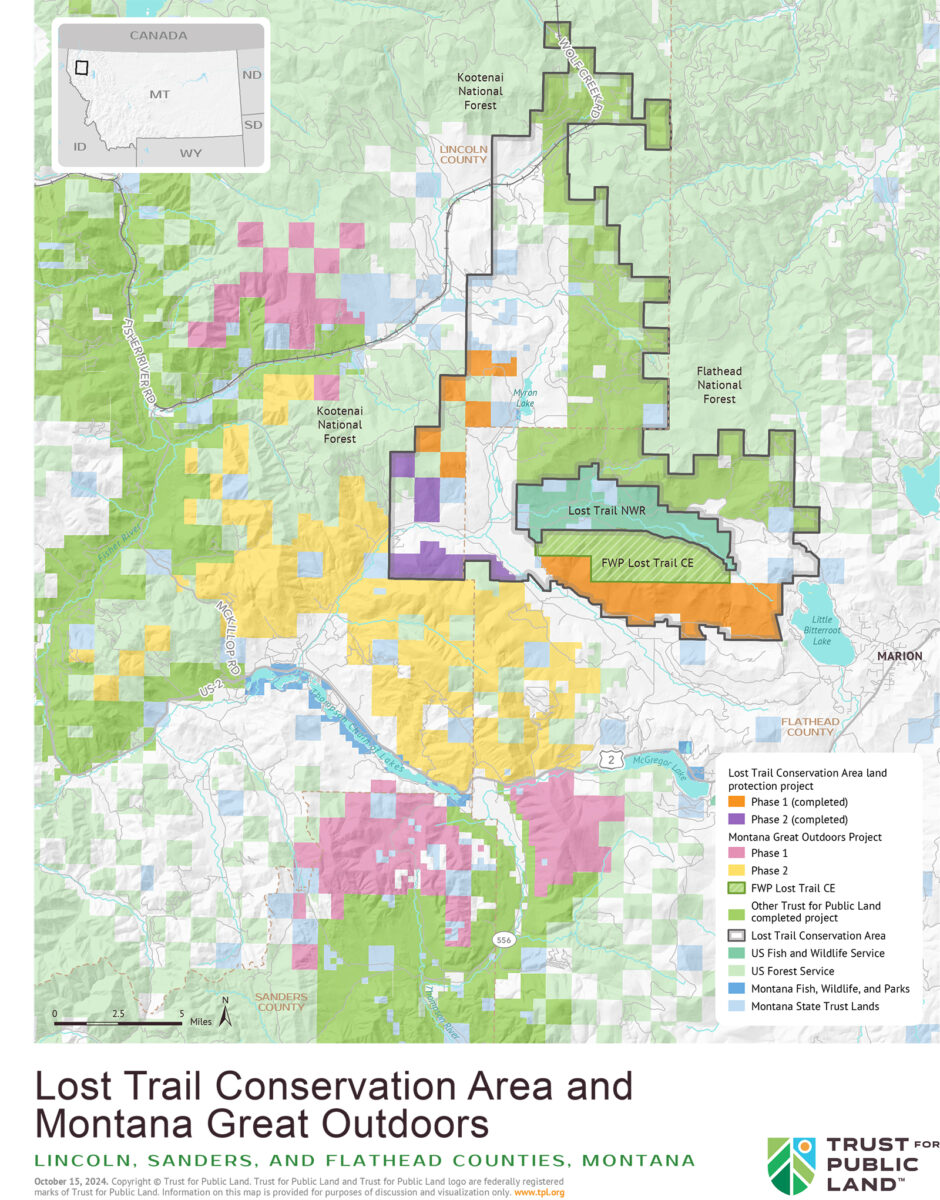

Called the Lost Trail Conservation Easement, the project shares nearly seven miles of border with the 7,876-acre U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) Lost Trail National Wildlife Refuge, and is the culmination of a partnership between FWP and Southern Pine Plantations (SPP), a real estate and timberland investment firm that in late 2019 purchased 630,000 acres of land from Weyerhaeuser Co., the timber giant that purchased the land from Plum Creek.

Initially, news of the purchase by SPP raised concerns among public land users in the region about whether the new owner might subdivide the parcels and sell them off for private development.

In finalizing the conservation easement, FWP, SPP and the nonprofit Trust for Public Land (TPL) eased those concerns. With funding from Habitat Montana, the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Trust, and, primarily, the U.S. Forest Service’s Forest Legacy Program, FWP secured the land’s development rights while SPP retained full ownership, harvesting millions of board feet of lumber per year while piping fiber into area mills.

The easement marked one of the most significant conservation achievements in the region in years, setting aside critical wildlife habitat and setting the stage for a series of other conservation easement opportunities on adjacent lands.

In 2021 and 2022, SPP sold 475,000 acres of newly minted Montana inventory to multiple interests, with Green Diamond Resource Company making the largest purchase at 291,000 acres. Those acres fall squarely in the footprint of the proposed Montana Great Outdoors Conservation Easement, a two-phase project totaling 85,792 acres of timberland and fish and wildlife habitat between Kalispell and Libby. On deck for final approval by the Montana Land Board on Oct. 21, Phase 1 affects a 32,981-acre property located in the Salish and Cabinet mountains.

As with the Lost Trail project, FWP would hold the proposed conservation easement, allowing Green Diamond to manage the land as a working forest while precluding development, protecting wildlife habitat, providing permanent free public access, and adding another piece of key landscape connectivity to the checkerboard.

According to the Montana Wood Products Association, which supports the Montana Great Outdoors Conservation Easement, the property currently produces approximately 2 million board feet (MMBF) per year, while Green Diamond intends to increase sustainable production to 9 MMBF by 2064. Many of the timber stands on the property are young, requiring time to mature as well as pre-commercial thinning treatments to be productive.

“Retaining these lands as a working forest is important to mill viability, particularly considering that 36 mills have closed in Montana since 1990,” according to Julia Altemus, executive director of the Montana Wood Products Association.

“The proposed easement can produce a sustained harvest of 20 MMBF of merchantable timber each year. This level of harvest will support 40 full-time workers and 100 seasonal workers,” Altemus wrote in a letter to the Land Board urging its support of the project. “Timber from this land would be processed regionally, generating $30 million/year in economic activity.”

The appraised value of the proposed easement’s initial phase is $39.5 million, with FWP securing funding amounts and sources including: $20 million from the USFS’ Forest Legacy Program, $1.5 million from Habitat Montana, which uses money from nonresident hunting licenses to enter land into conservation easements, and more than $4.1 million in private fundraising coordinated by TPL. Green Diamond Resource Company, meanwhile, will provide $13,827,604.80 (which is approximately 35% of the value) of in-kind contribution in the form of donated land value arising from the sale of the easement.

Because Montana statutes require FWP to gain approval of the Land Board for any “land acquisition” in excess of 100 acres or $100,000 in value, proponents of the easement will appear before the Land Board Monday to make their case for the Montana Great Outdoors Conservation Easement Project.

The board consists of Montana’s five top elected officials: Gov. Greg Gianforte, Secretary of State Christi Jacobsen, Attorney General Austin Knudsen, Superintendent of Public Instruction Elsie Arntzen, and Securities and Insurance Commissioner Troy Downing.

Zooming out on the broader patchwork of permanently protected, publicly accessible timber-producing parcels, the Montana Great Outdoors Conservation Easement project area borders Thompson Chain of Lakes State Park, the 142,000-acre Thompson-Fisher Conservation Easement, and the 100,000-acre U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Lost Trail Conservation Area, which includes FWP’s easement.

All combined, Altemus wrote to the Land Board, “this project will perpetually ensure area mills in the Flathead region will have a steady fiber supply. It’s this level of production needed to keep loggers, log trucks, and mills in operation. This production level is not a given. The proposal before the Land Board is a one-time, critical opportunity to secure this outcome for Montana. We are frequently asked what the state can do to support the forest products sector. These questions have increased with the recently announced mill closures in Seeley Lake and Missoula. One of the answers to that question is to support proposals that keep Montana’s working lands working and generating long-term, sustainable and reliable fiber for an industry that has faced significant reductions in recent decades.”

Of the roughly 150 comments submitted to the Land Board regarding the Montana Great Outdoors Conservation Easement project, including letters of support from the boards of commission in Flathead, Lincoln and Sanders counties, only one opposed it — WRH Nevada Properties, LLC, of Rexburg, Idaho, which owns mineral rights underlying approximately 95% of the area proposed for the conservation easement. According to FWP, the conservation easement will not have an adverse impact on the mineral rights or undercut the value of WRH’s mineral estate. According to FWP, a contractor, HyrdroSolutions, assessed the property and determined that the potential for development of the mineral estate underlying the proposed conservation easement is “so remote as to be negligible.”

Regardless of actual mineral potential, the easement’s terms would apply “only to the owner of the surface rights and would not impact third-party owners of mineral rights within the project area (unless those rights are subordinate to the conservation easement),” according to FWP environmental assessment of the project.

“Should a third-party mineral right holder discover marketable mineral resources in the project area, the conservation easement would not preclude that entity from developing and extracting those resources,” the assessment states.

Jason Callahan, Green Diamond’s policy and communications manager, said the Seattle-based company’s support for the project, as well as a suite of other conservation easements either proposed or completed on its checkerboard of Montana timberland, is rooted in its tradition as a family-owned forest management company.

“This conservation easement is attractive to us because we retain full ownership of the land and full management discretion. It’s called a conservation easement but that’s just the name we’re given. We consider it a working forest easement,” Callahan said.

Acknowledging the intensifying development pressures bearing down on private landowners in northwest Montana, including routine, unsolicited purchase offers, Callahan said simply, “we are not a real estate company.”

“We are a forest management company. That is what we do. We have been managing forests since 1890 and we want to continue managing forests. Our company’s president wants to see his grandchildren be able to access these forests. This is a generational investment. This land needs to rest. It needs sustainable forest management over the next 15 to 30 years before it’s capable of paying for itself again. And because our development rights have conservation value, this project allows us to monetize them. The conservation easements give us the bridge funding until these forests are back to full production.”

In exchange, Green Diamond gives up its development rights, the land remains on the tax rolls and the public is guaranteed permanent access to some of the best wildlife habitat in northwest Montana.

From a conservation standpoint, the property helps furnish a suite of wildlife species, including grizzly bears, with an unbroken corridor that allows them to travel between the Northern Continental Divide and Cabinet-Yaak ecosystems.

Back at FWP’s Lost Trail Conservation Easement, where the golden-hued leaves of cottonwood and aspen stands around Dahl Lake dappled in the October sun, Leah Breidinger, a habitat conservation specialist for FWP, passed through stands of Douglas fir, western larch, ponderosa and lodgepole pine. When she spotted a bristly patch of heavily browsed snowberry shrub, she reported her discovery to Anderson, who nodded with approval.

Although elk and mule deer populations are down, according to spring surveys, the conservation easement remains some of the best elk hunting in western Montana, and with additional pieces falling into place on the conservation map, both wildlife experts hope the populations will benefit from connectivity.

“The conservation easements are an important tool for us to keep those migratory paths intact and protect really important year-round wildlife habitat,” Breidinger said. “We’re lucky to have conservation partners like Green Diamond that purchased these lands because they have a long-term vision to manage the forests sustainably.”

As northwest Montana’s land ownership scales tip into balance, Anderson said he hopes the public sees the value in managing the landscape for multiple uses, including the recreation access the conservation easement guarantees in perpetuity.

“As times change and some of this land ownership changes, I think it’s starting to hit home with folks that it’s not just an open playground, it’s private property,” Anderson said. “Fortunately for us, we have had some really good partners who want to keep the working forests working. They’re in it for the long haul. Timber management and a healthy ecosystem are not opposing forces. They really can work together.”