City of Whitefish Defends Immigration Enforcement Policy After Venezuelan Man’s Detention

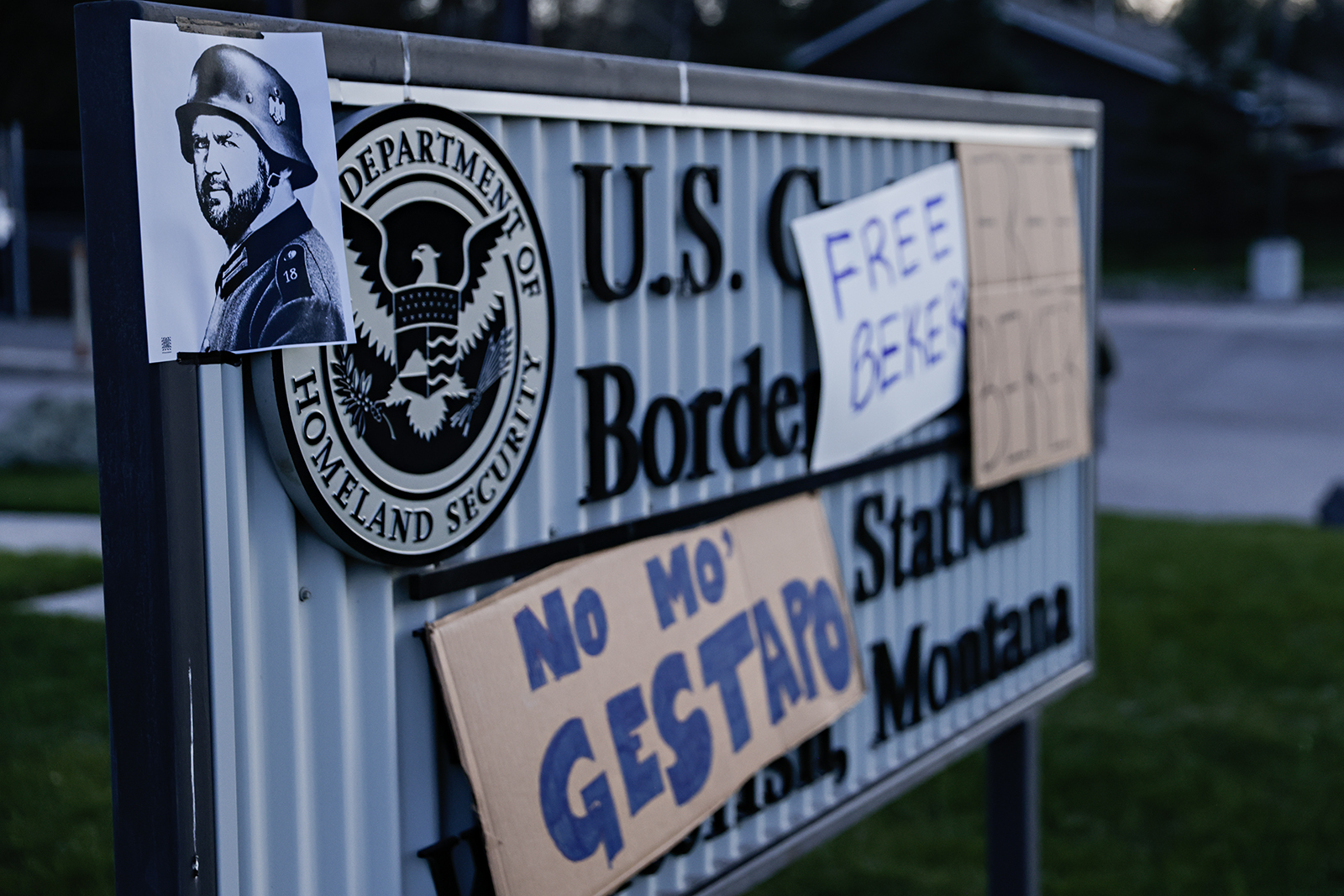

The April 24 arrest of Beker Rengifo-Del Castillo, who was transferred from Whitefish to an out-of-state detention facility until his April 30 release, prompted public demonstrations and raised questions about enforcement overreach by local authorities. On Monday, Whitefish city officials addressed those concerns.

By Tristan Scott

Federal immigration enforcement authorities say the April 24 arrest of a Venezuelan man who was authorized to live and work in the Flathead Valley was legally justified. So was the man’s transfer to an out-of-state U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) facility in Tacoma, Wash., where he was detained for nearly a week.

But residents of Whitefish, including some who attended daily demonstrations outside the local U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) office demanding the release of 33-year-old Beker Rengifo del Castillo, have publicly raised concerns about why the man was arrested at all, particularly since the Whitefish Police Department reportedly made initial contact with Rengifo del Castillo during a traffic stop over a burnt-out tail light.

On Monday night, facing a flood of questions from the public, members of the Whitefish City Council addressed those concerns and called on city officials, including Police Chief Bridger Kelch, to clarify the scope of the local department’s role in Rengifo del Castillo’s arrest.

“I think we need to be clear and transparent to our community about how we get from a traffic stop to the Border Patrol being there,” Councilor Steve Qunell said. “I don’t quite understand that process. I’ve been pulled over before and nobody asks me my immigration status.”

Kelch said the city has firm policies in place “that strictly prohibit biased-based policing and improper profiling,” while city officials issued a statement that “the Whitefish Police Department does not actively seek out immigration violations.”

“In fact, policies are in place that prohibit the detainment of any individual, for any length of time, for a civil violation of federal immigrations laws or a related civil warrant,” according to the statement.

On Monday night, council members pressed the police chief to explain how, then, federal immigration enforcement authorities had come to intervene during the traffic stop.

Whitefish City Attorney Angela Jacobs said Kelch was limited in what he could disclose about the traffic stop without compromising confidential criminal justice information; however, the police chief dismissed rumors that his officer called on CBP for language interpretation services.

“First of all, we did not call Border Patrol for interpretation services,” Kelch said, responding to what he called inaccurate accounts of the incident posted to social media. “Facebook was not accurate … we didn’t call border patrol; we called dispatch and they sent an officer over.”

Acknowledging that the intensifying pressure of immigration enforcement nationwide has crept into Montana and the Flathead Valley, Kelch said enforcement has been complicated by an evolving set of federal guidelines and executive orders.

“There’s been an uptick in immigration issues within Flathead County, and understanding immigration is difficult, especially today; there are a lot of court proceedings and rules that have gone out, it’s impossible to keep up with them on a daily basis,” Kelch told council, saying “the Whitefish Police Department does not enforce immigration law.”

“In this situation there was a question about immigration status due to a number of factors under reasonable suspicion that the [Whitefish Police Department] officer had,” Kelch said. “The officer contacted dispatch at the Spokane sector [of the U.S. Customs and Border Protection] and had them query the individual’s immigration status. I do not know what the result of that was. Our officer completed his traffic stop and issued a written warning for the violation that occurred.”

During the 14-minute traffic stop, Kelch said “the officer saw some things that raised his suspicious and he followed up. Whatever information that was provided to Border Patrol dispatch, they saw something they were concerned about and sent an agent to [Rengifo del Castillo’s] location and they took it from there. This is not common. This is not something we do all the time.”

The police chief said the department has reviewed its policy into what circumstances trigger CBP notification and is making adjustments.

“We have reviewed our policies and we’re learning from this situation,” Kelch said. “I’m putting some things in place, and making sure that a supervisor is notified prior to contacting Border Patrol. So there will be more discretion and oversight of those referrals.”

Whitefish City Manager Dana Smith said the police department is not among the Montana law enforcement agencies permitted to enforce federal immigration law under Section 287(g) of the Immigration and Nationality Act. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Flathead County Sheriff’s Office in 2020 signed a memorandum of agreement allowing the sheriff’s office to serve and execute warrants of removal and arrest for designated immigrants in county jail. The program streamlines the process of transferring immigrants into ICE custody.

The city of Whitefish does not have such an agreement in place, Smith said.

“We have no interest in participating in those agreements,” Smith said. “We’re not interested in doing the work of ICE; that is their job. We don’t want any part of that. We don’t have the funding or capacity.”

In their prepared statement, city officials said the Whitefish Police Department has a long-standing working relationship with Whitefish Border Patrol and “regularly assists one another with support services, such as traffic control, peacekeeping efforts, officer safety, and information sharing.”

“All individuals, regardless of their immigration status, should feel secure that contacting or being addressed by our officers will not automatically lead to an immigration inquiry and/or deportation,” according to the statement.

For Qunell, the city’s role in Rengifo del Castillo’s detention was “unfortunate,” but not the result of flawed local law enforcement policy.

“It’s really unfortunate that we are put in this position in our town of 8,000 or 9,000 people, that all of a sudden these issues are cropping up and it’s not because of us, it’s because of what’s going on at the federal level,” Qunell said. “There’s an erosion of due process. But I for one don’t think that responsibility lies with our local police force.”

“We also need to be accountable and we’re accountable to one another,” Kelch responded.

Andrea Sweeney, a Missoula-based attorney who assisted Rengifo del Castillo with legal support during his detention, said that accountability appears to be lacking at the federal level.

Sweeney said Rengifo del Castillo had been authorized to live and work in the Flathead Valley under the rules of a federal humanitarian program while his application for asylum or other legal status is processed. Specifically, he’d received authorization under a statutory provision called “humanitarian parole” which the U.S. government in 2022 and 2023 extended to nationals of Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua and Venezuela,” lumping the countries together under the “CHNV humanitarian parole programs” umbrella.

According to Sweeney, Del Castillo received his two-year grant of parole in April 2024 and obtained a work permit in July 2024, extending his rights to protection until July 2026.

Although the Trump administration on Jan. 20 instructed DHS to end the program and revoke the temporary protection it afforded tens of thousands of CHNV parolees, a federal judge in Massachusetts on April 14 signed a preliminary injunction in a lawsuit challenging the Trump administration’s widespread rescissions of migrants’ legally granted parole status.

Because Rengifo del Castillo’s arrest occurred 10 days after the judge issued the preliminary injunction, Sweeney said his arrest was not lawful.

But according to a statement CBP issued “in response to recent media reports and public demonstrations … Whitefish Border Patrol agents were compliant with federal immigration law and agency protocols.”

“While CBP does not comment on the specifics of individual enforcement actions due to privacy concerns, it is important to clarify that recent arrests conducted by Border Patrol agents are vetted and legally justified,” according to the statement, which says that “having a pending asylum application with [U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services] does not preclude ICE or CBP from placing you into removal proceedings.”

“Additionally, the parole program that allows individuals to temporarily enter the U.S. does not confer legal immigration status. The parole program is a discretionary measure intended to address specific humanitarian needs, not a guarantee of permanent residency,” the statement continues, citing federal statute that says parole “shall not be regarded as an admission” and “may be revoked at any time.”

The statement from CBP also defended the legality of transferring an individual to an out-of-state detention facility.

“Individuals paroled into the U.S. remain subject to enforcement actions, including expedited removal, with access to asylum screenings and due process,” according to the statement. “As part of removal proceedings, U.S. Border Patrol transfers custody of illegal aliens to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) for further processing. The subsequent discretionary release of an individual by ICE — whether on parole, bond, or recognizance — does not imply that the initial apprehension by Border Patrol was unlawful. Border Patrol agents operate under clear legal authority, and our enforcement actions are conducted in compliance with federal law and established procedures.”

Whitefish City Councilor Rebecca Norton, who participated in the demonstrations protesting Rengifo del Castillo’s arrest outside the Whitefish CBP office, said that despite the “chaos” occurring at the federal level, she was satisfied the local police had acted according to policy.

“I think that when people read through [the department’s immigration enforcement policies] they are really well intentioned for local police,” Norton said. “I think we’re all going to be learning as we go because we’ve never seen some of these things that we’re seeing right now and so people are on edge, me included.”