BROWNING – The walls of Chief Earl Old Person’s office are lined with paintings of past chiefs. Each image features a stoic, commanding face, similar to his own. These portraits reflect the history and pride of the Blackfeet people, a past many on the reservation are forgetting, says Old Person, who has been a cultural guardian and political leader on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation for six decades.

Old Person, now 84, has served on the Blackfeet Tribal Business Council off and on since 1954, serving as chairman for much of that time. He was ousted in 2008, but reelected in 2012 to a governing body that has since been mired in controversy. In 1978 he was given the title of chief, a lifetime appointment he will take to the grave.

“This is life,” he said.

Old Person is waging a quiet battle to save the Blackfeet culture and its people. He believes the problems the tribe faces today – perpetual unemployment and endless political unrest, among others – are rooted in the disappearance of the tribe’s traditions and heritage.

“We had something to base ourselves on,” he said. “And now that’s gone.”

Earl Old Person was born on April 13, 1929 and grew up near the Starr School, about 10 miles outside of Browning, close to where he lives today. Blackfeet was his first language and he had to be taught English as a child. In the late 1940s, he spent summers working on a track gang for the Great Northern Railway so that he could buy new clothes for school. In 1952 he got his first job at the tribal land department.

It was there he forged relationships with tribal councilors who encouraged him to run for office because of his relationship with elders. In June 1954 voters elected him from a field of 64 candidates. He soon came up through the ranks and became chairman of the nine-person board, a position he held for decades.

Prior to the 1930s, chiefs traditionally led the Blackfeet tribe. With the death of Chief John Two Guns White Calf in 1934 and the establishment of a council, the position sat vacant for 44 years, until 1978 when Two Guns White Calf’s family bestowed the honorary position upon Old Person. As chief and chairman, Old Person has met every United States president since Harry Truman and was even invited to Iran in 1971 to celebrate the 2,500th anniversary of the Persian Empire.

A champion for civil rights and cultural preservation, he has served as president of the National Congress of American Indians, holds an honorary doctorate from the University of Montana and was awarded the Jeanette Rankin Civil Liberties Award by the American Civil Liberties Union of Montana. In 2007, he was inducted into the Montana Indian Hall of Fame.

In 2008, he lost his spot on the council in an election that replaced all four incumbents. After leaving office, he began working on a compilation of native songs and stories. But as the 2012 election approached, tribal members once again urged Old Person to run.

“I really didn’t want to go back in,” he said. “But there were some things I saw that needed to be done, that I could help with. But still, we’re having problems.”

Since early 2012, a bizarre political saga has unfolded on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation that has brought about the suspension of seven councilors, dozens of tribal employees and even an attempted government takeover.

The tribal council began fracturing a few months before Old Person was reelected in 2012, when it suspended councilor Jesse “Jay” St. Goddard for authorizing an illegal moose hunt. In 2013, St. Goddard pleaded guilty to federal charges.

In July 2012, a month after the tribe’s biennial election, a group of councilors contested that St. Goddard’s suspension was illegal because only six of the nine councilors voted on the matter. According to the Blackfeet Constitution, a council “may expel a member for cause by two-thirds or more members of the entire Blackfeet Tribal Business Council voting for expulsion.”

On Aug. 19, 2012, councilor Paul McEvers was suspended for violating Tribal Ordinance No. 67, which protects the council from threats and intimidation. The council, including Chairman Willie Sharp Jr., alleged that McEvers had used tribal office equipment to prepare petitions to remove some members of the council.

A week later, a group of councilors who supported McEvers voted on a resolution to suspend Sharp, Old Person, Shannon Augare, Forrestina Calf Boss Ribs, and Roger Running Crane, and form a new council. None of those actions were taken and soon after, on Aug. 27, Chairman Sharp declared a state of emergency. That same day, Sharp led the council in a vote to suspend Cheryl Little Dog, Bill Old Chief and Jay Wells. In a press release, the ruling council said the suspensions were necessary to protect the tribe and that the councilors had “grossly violated the Blackfeet Constitution and their oath of office by attempting to form a new Tribal Council.”

Following the suspensions, Sharp ruled with a partially vacant council. Dozens of tribal employees have been fired and protests have become common in Browning. Tensions came to a boiling point this fall when, on Sept. 3, 2013, seven protesters were arrested during an attempted takeover of the tribal council.

|

|

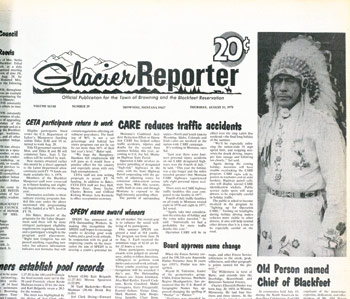

The front page of the Glacier Reporter newspaper from Aug. 31, 1978, reporting that Earl Old Person was named chief of the Blackfeet. – Greg Lindstrom | Flathead Beacon |

Last week, on Oct. 16, the saga took another turn, when Sharp personally suspended Augare, who is facing federal charges of drunken driving, and Leonard Guardipee, a councilor who was appointed to replace Wells. Sharp cited Augare’s pending court case and Guardipee’s recent conduct on a trip to Washington, D.C., where Guardipee apparently missed important meetings. However, the next day, acting secretary Running Crane issued a press release saying that Augare and Guardipee were still on the job and that Sharp’s order was illegal. Sharp refuted that statement and said he still had control over the government and that both councilors were out.

Old Person said in his more than six decades in tribal government, he has never seen a council as dysfunctional as today’s, adding that it has punished councilors for having different opinions and has made up its own rules. He lay much of the blame on Chairman Sharp and said the council is now more interested in “petty” matters than actual governance.

“Attacking one another all the time is not leadership,” he said. “If there is something wrong, it’s up to us to sit down and talk to the people… I don’t blame the people for protesting and letting their leaders know that they don’t agree.

“We held this tribe together,” Old Person said of past councils. “But today, everyone has their own mind and their own ways.”

Sharp said he respectfully disagrees with Old Person’s assessment of his administration, saying that he simply has a different style of leading. Sharp cited his own experience as the principal of Browning Middle School from 2000 to 2006 and his master’s degree from Montana State University.

But Old Person says a degree doesn’t mean someone can lead.

“In the past the elders didn’t have a lot of education or degrees, but they knew what to do,” Old Person said. “The people today don’t have the experience.”

But it’s not just a lack of leadership and political unrest that bothers Old Person. In 2013, the Blackfeet Indian Reservation faces a gamut of challenges, including rampant unemployment, environmental concerns about oil exploration and the disappearance of the Blackfeet language.

With unemployment hanging between 60 and 80 percent, many on the Blackfeet see oil development as the ticket to prosperity, including Old Person. However, environmental groups both on and off the reservation are worried about the effects of hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking,” especially on the eastern front, near Glacier National Park.

“People are concerned that (fracking) is going to cause problems for us and if it does we don’t want it,” he said. “But it also hurts our economy if we don’t let people come in and do these things.”

However, Old Person said at times the biggest hindrance to economic development on the reservation is the tribal council itself and its constantly revolving membership. He said when a new board is elected its members attempt to start their own economic projects, discounting the efforts established by previous boards, which flounder and fail. Old Person said that’s what happened in the 1980s when a long-established pencil factory closed because it didn’t have the support of the council.

But when you ask Old Person to identify the biggest problem facing the Blackfeet people in 2013, his answer isn’t about a long-closed pencil factory or oil rigs on the eastern front. It’s all about heritage.

Old Person is one of a shrinking number of Blackfeet linguists on the reservation and he is continually frustrated with the lack of interest young people have in learning the language. He’s also one of the few elders who remember the many traditional songs and dances. It’s not uncommon to find Old Person performing ceremonies on and off the reservation.

“It would take many lifetimes to learn what he knows,” said Blackfeet Community College Professor Marvin Weatherwax Sr.

According to Old Person, young people don’t have the respect for elders and tradition that they once had. He recalled an incident in Canada a few months ago where, during an historic ceremony, he saw two girls with their heads down texting instead of dancing. He said people are more interested in themselves than their community.

“There is no respect anymore. A kid can run over an elder and think nothing of it,” he said. “When you have that type of change with your people, you’re going to have that type of change in your government.”

Old Person hopes people will take the opportunity to learn the Blackfeet songs and language before he’s gone. He often encourages people to record him during ceremonies and said the only way people will learn the language is by hearing it, just like he did.

He said a renewed focus on the tribe’s traditions would not only preserve his people’s heritage but could bring unity to the nation and its government. Old Person is in the twilight of his political career, but he believes he can still do some good before he’s gone, before his presence is reduced to a painting on the wall.

“It’s challenging,” he said. “But I don’t mind being here if I can help and I’m going to do everything I can to bring these people back together.”

RELATED: Blackfeet Council Splinters Over Series of Suspensions