Eighty-six years ago, Carlene Brooner didn’t walk to the one-room schoolhouse in Lower Valley through four feet of snow, uphill both ways.

Brocken School was only about a quarter of a mile away from her home; the way she figures it, she was probably the closest student to class in those days.

“I have trouble, because I can’t say I walked to school for two miles in the snow,” Brooner said with a laugh last week from her cozy apartment at Buffalo Hill Terrace in Kalispell. “But then our house burned down and we moved, so I was two miles away then.”

Born in 1924 in Lower Valley to a farming family, Brooner’s first experiences in that tiny school were the foundation of what would become a life full of teaching, travel, and tenacity. Now 92, Brooner is sharp and funny, her wit as dry as Northwest Montana forests in the summer as she recounts more than five decades of life as a teacher.

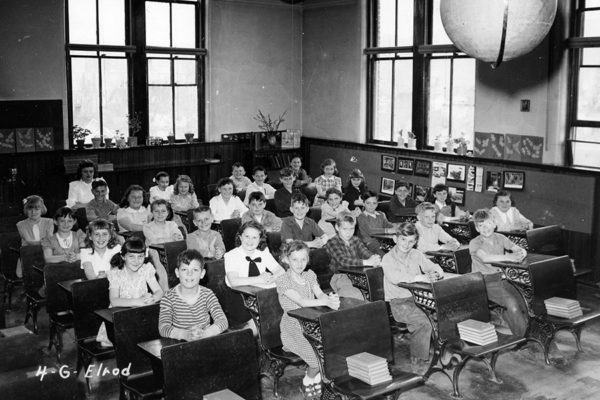

Plenty has changed since she first started teaching at age 18 in Somers in 1943 – for example, kids have cell phones in class these days, whereas the most distracting paraphernalia in Brooner’s early classrooms were marbles and comic books – but what strikes her is what hasn’t changed.

The expectation of the coming school year, the thrill of younger students learning anew, and the challenge of a new class becoming one cohesive unit are all still aspects of modern schooling. Though she hasn’t been in a classroom in an official capacity since 1990, some parts of it stay with her.

“I do miss the smell of Crayolas,” Brooner said.

The end of summer is a liminal time, when kids span the distance between the previous grade level and the next one, and parents prepare their kids with supplies and offer prayers of thanks that the school year has finally started again, while in the same breath praying to somehow stop their children from growing up so fast.

Heady and full of promise, the school year is order after a summer of controlled chaos, when teachers like Carlene Brooner wrangled her students, tan-limbed and wild, back into school shape.

But her educational experiences started just after the Great Depression had settled in the Flathead Valley, when everyone had nothing so no one felt deprived by comparison.

“Keeping up with the Joneses was out,” Brooner said. “Everybody shared what they had.”

As a first grader, there were only three other students at school, and they were seventh and eighth graders.

“The oldest boy drove a Model T coupe with a rumble seat,” she said. “Nobody else had one. A seventh grader driving one wasn’t seen as out of the ordinary then.”

Brocken had about a dozen students by the time she left for Flathead High School, where she graduated in 1941. After two years learning to teach at Northern Montana College in Havre, Brooner came back to the Flathead in 1943 for her first job teaching fourth graders in Somers. She was 18 and her last name was Wilke, and her boyfriend, Ernest Brooner, was overseas fighting in World War II. He had signed up on Dec. 8, 1941, the day after Pearl Harbor was attacked.

That first year in Somers taught her as much as it did her students, Brooner said. There were three girls and 10 boys in the class, and they were “well organized.”

“I learned a lot that year,” Brooner said.

A couple of her original students, Howard Ruby, 81, and Jerry Siderius, also 81, remember their fourth-grade teacher well.

“I had all good teachers in grade school,” Ruby, who still lives in Somers, said. “I can remember being at the old school in Somers before it burned down.”

Siderius remembers the Wilke family being from the Lower Valley, and that Miss Wilke, as she was known then, was a favorite among the boys in the class.

“She was a pretty gal,” Siderius said. “She was young and the boys thought she was pretty.”

He also remembers running into Miss Wilke while working his paper route for the Missoulian. He and his brothers would get up before dawn to deliver the news at 5:30 and 6 a.m., and during one especially cold winter, he passed his teacher while he rode his bike down School Addition Road.

“It seemed to me like she used to feel sorry for me,” Siderius said, laughing.

Life was different back then. Boys and girls were separated during recess, and marbles and comics were the contraband. The boys wore high-top boots to hold their jackknives, and they would play mumblety-peg, a game in which knives were thrown into the ground to stick in the ground as near the thrower’s feet as possible. Whoever got the closest and buried their knife the deepest won, and the loser had to pull out the knives from the ground with his or her teeth.

When Ernest came home from war, the two were married. Coincidentally, they married on Dec. 8, 1945, Brooner said, four years to the day after he entered the military. Carlene and Ernest would stay married for 62 years, up to his death in 2008 at age 84.

In the U.S. Navy, Ernest was trained in radio, radar, and sonar, and when he returned to the Flathead, he took a job at KGEZ. They lived near the station, Brooner said, because someone had to put wood in the fire.

The couple then moved to Yakutat, Alaska for a year, where they were exposed to a different way of life.

“The living was somewhat interesting,” Brooner said. “You scrounged your furniture from abandoned buildings.”

The Brooners came back to Montana after a year in Alaska, and had children in 1949, 1951, and 1953. Carlene went back to teaching, though her contract was not renewed one year when the administration found out she was pregnant and going to need time off to give birth during the school year.

“That was the way teaching was,” she said. “In those days, you had to sign a contract that said you couldn’t drink or smoke.”

(Brooner reports that while she did not smoke, she did, in fact, drink alcohol during those times, though not in public.)

When Ernest got a job with Ford, the family started traveling internationally, first to Alaska again, then to Bangkok from 1965 to the beginning of 1968. The family then came back through Alaska, and Brooner kept teaching. While teaching at a military base in Kenai, she remembers engineers installing a massive computer, which needed a whole air-conditioned room for its tubes machinery.

It was a good time for the family, Brooner said, because the traveling was still relatively easy on the children. But when Ernest’s job had him going back overseas, Carlene and the children stayed in Kalispell.

She went back to teaching locally, bringing her knowledge of the greater world to the small classrooms here.

“(Most of my students) had not been out of the county,” she said. “How do you explain the world to them?”

Howard Ruby’s wife, Frances Ruby, was on the school board in Somers when Brooner taught.

“She was a wonderful teacher, I remember that,” Frances Ruby said.

In 1990, at age 65, Brooner retired after nearly 50 years of teaching.

These days, Brooner revels in retirement. She had two goals for her twilight years: to sleep in and to read as much as she wants. Her favorite books are about geology, social anthropology, and mysteries, though it’s nearly impossible to keep up with all the advances in geology and anthropology anymore.

She watches the valley continue to evolve, and its students with it. Now kids are wired up when they hit the schoolyard, with gadgets galore.

“I can’t imagine,” Brooner said. “I thought it was bad enough when backpacks came to school.” (They were terrible on books, she said, leaving them dog-eared and “busted up.”)

She also thought Velcro would be a great invention, until her students absentmindedly ripped it up and down in class. Ballpoint pens were another much-touted creation, but the kids just took them apart and used them for nefarious purposes, like spitballs.

People didn’t snap 100 pictures a minute back then, and communities seemed more stable, with nearly everyone at the same stage of life. Her biggest regret from her half-century of teaching was not getting more involved in her students’ home life, and she also wishes she had more than one reading series with which to teach.

It was a good, challenging job, one that remained interesting and kept her brilliant mind open, searching, and learning. She keeps sharp with her reading, and stays in touch with her children every day through email.

But even after 92 years, when the breeze takes on its first bite of the autumnal season and the go-go days of summer come to a close, she still thinks of Crayola crayons.

“That was one thing you always got new,” Brooner said.