Callie Langohr likes to save mementos. There’s the little school bell she would play with as a child alongside her sister, two girls growing up in Kalispell dreaming of being teachers. There’s the tattered, plaster wolf statue with a scuffed nose, an unintentional yet apt symbol of Glacier High School’s early years. And there’s the old-time wooden ice cream maker, a thrift store bargain that served as a humble homecoming trophy when it all started 10 years ago.

Some of these keepsakes sit near Langohr’s principal’s office at the west entrance of Glacier High School. Others are spread throughout the campus like Easter eggs. They each tell a story, and collectively they help tell the tale of how Kalispell boldly reshaped its academic identity and evolved into a town with two public high schools.

This year marks a decade since that transformative moment officially arrived, changing the community forever. In that relatively short amount of time, Kalispell has changed dramatically and nurtured success at both Glacier and Flathead.

Both schools tout impressive academic marks, including two of the top Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate programs in Montana and the second highest combined graduation rate among the state’s largest cities.

They both have performed well in athletics and activities, winning individual and team state championships and developing nationally ranked talent, including a pair of perennial speech-and-debate powerhouses.

And following the passage of the latest bond, which will invest $19 million into upgrades and deferred maintenance at Flathead, any lingering resentment that surfaced in the wake of Glacier’s $36 million facility has all but evaporated, creating a healthy crosstown rivalry that now illuminates a collective pride and spirit of perseverance.

But getting here wasn’t easy.

By the late 1990s, it was obvious and unavoidable — Flathead High School was bursting at the seams.

The county’s first high school, built in 1903 in a quiet neighborhood on the western outskirts of a burgeoning downtown, had undergone a variety of renovations, expansions and realignments over the century to address the rising tide of students.

By the time the 2000s arrived, Flathead’s high school enrollment had spiked 20 percent in a decade as Kalispell boomed with the rest of the valley. The school district featured an odd makeup — elementary students would attend kindergarten through sixth grade at their neighborhood facility, then go to Linderman in downtown for seventh grade before bouncing to the junior high school for eighth and ninth grades until finally ending up at Flathead High for sophomore through senior years.

At the time, the last city to expand and build a Class AA high school was Billings in 1986. But as the Kalispell community began to grapple with a solution to Flathead’s overcrowding, it became quickly apparent that any change would likely mean shifting the entire educational landscape.

“It was a really gut-wrenching process to decide what we were going to do,” Don Murray, a longtime member of the school board, said.

School superintendent Harry Amend began organizing community meetings, the school board started crafting options, and citizen groups were established to study alternative ideas. In the end, three main scenarios emerged: build one big high school and close the existing Flathead; build two brand new high schools and revamp the existing Flathead; or build a new high school and remodel a portion of Flathead.

The decision loomed large, with debate centered heavily on the cost and consequences of each choice. To gauge public opinion, the school district sent out roughly 24,000 surveys asking residents for their top choice. About 20 percent of people responded, and the overwhelming majority picked the third option: constructing a new high school that would supplement Flathead.

But faced with the landmark decision, the school board balked. Instead, board members in the spring of 2001 voted to build one big high school that would keep the town united under Flathead.

“It was very, very difficult for the school board to say we’re going to split this community into two schools,” said Tony Dawson, a member of the Evergreen school board who was involved in the planning process and would later join the Kalispell board.

“That was such a hard decision.”

The fallout was significant. Community members loudly rebuked the board’s decision, leading all but three of the board members to step down. Amend accepted another position out of state as school superintendent. Kalispell returned to the drawing board.

“There was a lot of pain over that whole thing,” Dawson recalled.

In 2001, Darlene Schottle arrived from Reno, Nevada, where she had helped lead a school district with 80,000 students and expand it from 10 to 12 high schools as the superintendent.

“Darlene came in with fresh ideas and a fresh view on everything, and she had no baggage,” Dawson said. “She started the whole thing over again.”

With regular public meetings and planning sessions, the community came to terms with a simple yet tough reality: a second high school was inevitable.

“What I didn’t understand back then was going from 10 to 12 schools is much different than going from one to two — it’s much harder,” Schottle, Kalispell’s school superintendent at the time, said.

“It was a cultural shift,” she added. “And it was a real wakeup call for me. I understood what the process would be like, but the emotional tie of a community to their high school, especially in Montana, is a very real thing.”

Brad Walterskirchen, a Flathead graduate and third-generation member of the school board, said the decision to break Kalispell into two schools weighed heavily on the board members’ minds.

“We had some pretty good arguments,” he said. “I remember a few people said, ‘If you do this, we will never win a state championship in Kalispell again.’”

For Walterskirchen, the potential missed opportunities for championship glory were offset by the missed opportunities for a large portion of kids who couldn’t participate in their favorite activities because of Flathead’s sheer size.

“A lot of kids were being left behind at a big school like that,” he said. “I just thought it would be really neat if there could be two bands, two drama clubs, two wrestling teams. Just think of how many kids would be able to participate in activities and receive a better education in a smaller school setting.”

On the night of Nov. 2, 2004, Schottle and others gathered in the basement of the public library in downtown Kalispell awaiting results from the historic bond election. By a 55 to 45 percent margin, voters approved $39.8 million to build a new high school and renovate part of Flathead. A separate bond for the elementary district was also approved that set aside $10.9 million to renovate the junior high.

Reflecting the community’s heightened interest in the proposals, the bond elections drew the largest voter turnouts on record in the community — 92 percent in the elementary district and 90 percent in the high school district.

“We got phenomenal buy-in,” Dawson, another Flathead grad, said. “For the community to actually support splitting themselves into two, I always have been amazed at that.”

“Frankly, I wasn’t shocked,” he continued. “There was a huge amount of work that went into it. And we had to feel the pain of slowly coming to the realization that this one giant school was not good for this community.”

Swank Enterprises was selected to build the new high school on a seemingly faraway piece of open land on the north end of Kalispell, which was all but empty at the time. CTA Architects Engineers was hired to design the massive new structure.

To develop the specific details of the new school, someone with a strong attention to detail and a keen educator’s mind was needed.

Langohr, a 1971 Flathead graduate, had returned home in 1993 and served as a guidance counselor at Flathead for five years before becoming assistant principal. After only one year, she was named principal. After the bond approval for a new high school, Langohr applied to be the project manager and future principal for the new school. She won the job.

“I believed that it was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to make a difference in the lives of young people for generations,” Langohr said. “All of a sudden, we had this opportunity in a community that is so supportive of kids and education. It was a dream come true.”

Langohr devoted an entire year to solely focusing on the list of line items necessary for the new school, which numbered over 1,300. Staff, curriculum, school colors — every single aspect required attention. Community and student groups were formed to tackle the big decisions, such as the name and mascot. Months of debate raged over those contentious items, but nevertheless the school began surfacing, piece by piece.

“I needed to do whatever needed to be done and take care of all those details to make sure Glacier opened on time, under budget and in a manner that took care of people,” she said.

“We knew this was going to stay with us for a long time. We wanted to make it unique. We had a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to do things differently … It all came together. All the stars aligned because we had good people all around.”

Langohr, other administrators and board members even traveled to Coeur d’Alene to meet with school staff and learn how they had expanded over the years.

“We never scrambled,” Langohr said. “We never panicked. We had a committed group of people that had a sense of what this needed to look like. They had a sense that it was a calling. And we wanted to do it right.”

On Sept. 4, 2007, the first day of school commenced and students streamed through the halls and filled the classrooms. Homecoming week arrived a few weeks later, and instead of a big public ceremony, the students and staff gathered in the parking lot and celebrated with a makeshift parade. The top “float” received a modest prize: an old ice-cream maker found at a local thrift shop.

In that inaugural year, only freshmen, sophomores and juniors attended Glacier. Juniors were allowed to choose which high school they wanted to attend, and underclassmen with siblings at either high school were also allowed to choose.

“It was pretty amazing to be starting in a new place,” said Chad Dawson, a junior at Glacier in 2007 who became the first student body president. “The thought of splitting from friends was tough.”

Immediately, Glacier faced the tough task of laying the groundwork for everything. The school’s sports teams, made up entirely of underclassmen and athletes without prior varsity experience, faced stiff competition.

“Starting a new high school and not having seniors was a unique challenge and we knew we had to rise to the challenge,” Chad Dawson, Tony’s son, said. “And it didn’t come without its hiccups. But it was a really good challenge.”

The Glacier football team lost every game that first season and was outscored by opponents a combined 487-65. The other athletic teams suffered similar fates early on.

“We took our lumps, but one of the things I’m most proud of is that we came to practice every day and tried to have fun,” said Shay Smithwick-Hann, a sophomore at Glacier in 2007 who served as the starting quarterback through his senior year.

“We showed up and tried to get better and hopefully build a strong program and build something that would last.”

Smithwick-Hann credits coaches like Grady Bennett, who took over the football program, and Mark Harkins, who led the boys basketball program, with building strong foundations around hard work and positivity. Chad Dawson credits teachers at Glacier with instilling similar attitudes and mindsets, which became contagious.

Through tough times, Glacier built a tough-nosed identity.

“That beginning, that very first year, that’s when we developed the personality of Glacier,” Langohr said. “There are some key things that came out of that first year. It developed our Glacier grit, that perseverance. Our kids faced a lot of adversity that first year. But they came out of it with a positive attitude and they didn’t quit. They never, ever quit on us.”

Ten years later, Glacier has already established a rich tradition in both academics and athletics. The school is home to numerous individual and team state championships, including in boys basketball, softball, football and speech and debate.

This year, the school is among four high schools selected for having the most memorable graduation ceremonies in the nation, and it will find out in May if it was selected No. 1.

“Our vision is to be one of the top high schools in the nation, and we make no bones about it,” Langohr said. “On initial blush, that may sound arrogant, but we’re real clear with our students, our community, and our parents — if you graduate from Glacier High School, you are on an even playing field with all other graduates. You can sit down at the table and compete to get into a military academy, to try and get a job, to try to go to a vo-tech school, to try to go to an Ivy League school. Whatever your dream is, you’re given that initial skillset to compete on a level playing field.”

Yet Glacier’s prominent emergence has sparked some animosity across town over the years. Those remaining loyal to Flathead have felt the original school was disregarded and forgotten. Some believe Flathead did not receive enough attention or investment from the original school bond and planning process. The high school did receive $5 million from the Glacier bond to create a new commons area, but most of the attention was centered on getting Glacier established.

“I think we underestimated that Flathead was really a new school, too,” Schottle said. “It wasn’t a new building, but it was a new school. They really had to reconstitute themselves as well and create an identity for themselves, too. I don’t think we contemplated the significance of that change for Flathead as much. I don’t know exactly what we could’ve done, but I think there should’ve been a lot more acknowledgement that we had two new schools that were going to start building their programs.”

At the time, the high cost of building Glacier was enough to create heartburn among the school board and community members who wanted more for Flathead. Would increasing that original bond request threaten to derail the creation of Glacier?

“It’s hard to say,” Walterskirchen said. “There’s always been a bit of resentment that Glacier got all the new stuff and we’ve got an old, beat-up building at Flathead.”

The latest school bond, approved last fall, will infuse $19 million into Flathead and address a large portion of the remaining facility issues. Many believe — and hope — this will help settle any animosity that still exists between the two school communities.

Indeed, both Glacier and Flathead have experienced ups and downs during this evolutionary process, grappling with change while experiencing the inevitable growing pains. And with Kalispell’s embrace, the two schools have forged unique identities that appear to be only getting stronger.

“People said, ‘You’re going to split this town. People are going to hate each other.’ But I think it’s quite the opposite now. The competition is good,” Walterskichen said.

“I’m a Flathead High School graduate. I love Flathead High School. There are a lot of great things there and a historic tradition. Glacier is a phenomenal school. And now there’s a place for everyone. That’s made our education system here in Kalispell so successful.”

For all the ups and downs, hours of debate and years of work, both schools — and Kalispell as a whole — have plenty to be proud about.

“It was hard work,” Langohr said. “But I’d have to say, of the five things in my life that were incredibly hard but just absolutely fulfilling, (establishing Glacier) is on the list.”

“Easily.”

The Tale of Two Schools

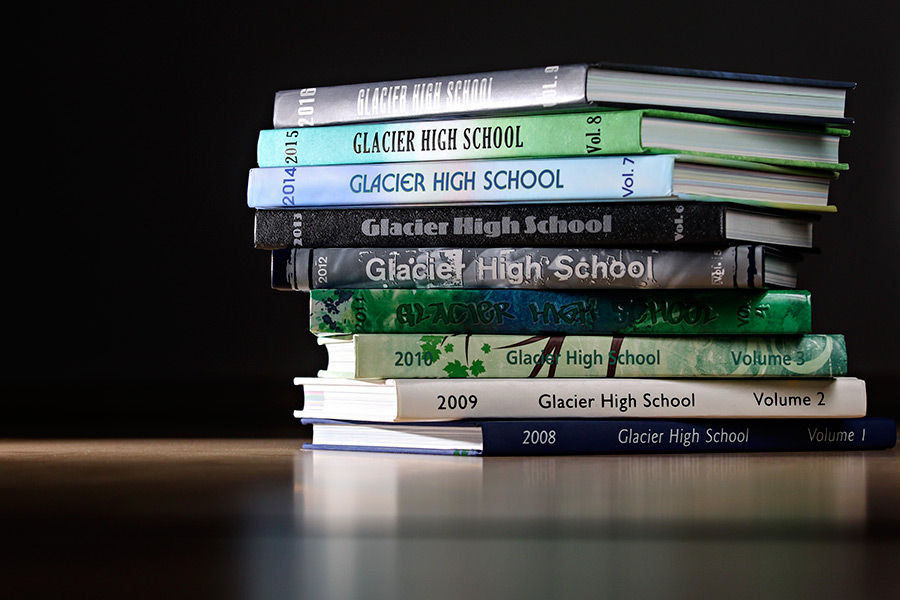

A timeline of Glacier High School

1903: Flathead County High School is constructed.

1998: Enrollment spikes nearly 20 percent in a decade and approaches 2,500 for the first time at Flathead, which becomes the largest high school in the state.

November 2000: Planners, school staff and community members begin reviewing options to address persistent growth at Flathead High School. The ideas include building one big new school; building two new schools; or building a new school and renovating the existing Flathead. School officials survey about 24,000 residents and roughly 20 percent respond, a majority of whom overwhelmingly support building a new high school that would supplement Flathead.

March 2001: The school board reviews the survey results supporting a new smaller high school and debates the merits and consequences of splitting Kalispell into two schools. In a reversal, the board opts to approve plans to build one big new high school.

2001-2003: Significant public outcry leads the school board to back off plans to build one big high school. The school board hires Darlene Schottle in July 2003, and Schottle begins organizing public-planning committees and events to review options for the future of Flathead.

Nov. 2, 2004: By a 55 to 45 percent margin, Kalispell voters approve a $39.8 million bond to build a new high school and renovate part of Flathead High School. A separate bond request for $10.9 million to renovate the junior high passes by a 60 percent margin. The historic bond requests draw the largest turnouts on record: 92 percent in the elementary district and 90 percent in the high school district.

Aug. 11, 2007: More than 200 people attend the dedication ceremony for the new $37.4 million Glacier High School, the first AA high school to open in Montana since 1986. Sen. Max Baucus, D-Mont., delivers the dedication speech, applauding the community for coming together to create the new school and providing more opportunities for students.

Aug. 24, 2007: The Glacier High football team plays its first varsity game and the first sporting event for the new high school. Butte defeats Glacier 40-7 in Legends Stadium. Sophomore quarterback Shay Smithwick-Hann scores the first touchdown in school history, a 6-yard run. Junior Taylor Graham makes the first tackle.

Sept. 4, 2007: The first day of school commences at Glacier High School. The inaugural academic year features roughly 900 students and only juniors, sophomores and freshmen. Flathead’s enrollment is 1,640.

Oct. 9, 2007: With only juniors and sophomores, the Glacier boys golf team wins a share of the Class AA state championship, tying Billings West with 622 points. Junior Larry Iverson III captures the individual state title.

Feb. 9, 2008: Flathead wins the wrestling state championship.

Aug. 29, 2008: The Glacier football team wins its first game, a 21-14 road victory over Butte in the opening game of the program’s second season.

Feb. 14, 2009: Flathead wins its second straight wrestling state championship.

June 8, 2009: Glacier graduates its first senior class. A total of 236 students graduate.

Feb. 13, 2010: Flathead wins its third consecutive wrestling state championship.

Jan. 29, 2011: The Glacier speech and debate team wins its first state championship.

January 2012: The Glacier speech and debate team wins its second state championship.

March 9, 2012: The Flathead and Glacier boys basketball teams meet in the semifinal round of the state championship tournament in Bozeman. Flathead wins 63-58.

Sept. 29, 2012: The Glacier boys golf team wins the state championship.

Feb. 11, 2012: The Glacier wrestling team wins its first state championship.

May 2012 — The Glacier girls tennis team wins the state championship.

January 2013: The Glacier speech and debate team wins the state championship again.

Nov. 21, 2014: The Glacier football team defeats Great Falls C.M. Russell 56-19 in the Class AA championship game inside Legends Stadium in one of the most dominating victories in a state title game in Montana history. By winning a state title in only its eighth season as a program, the Wolfpack become the second fastest Class AA team to achieve the ultimate prize.

January 2014: The Glacier speech and debate team wins its fourth state title.

Spring 2014: Graduation rates at both Flathead and Glacier reach roughly 85 percent, up from 74 percent in 2010.

May 23, 2015: The Glacier softball team wins its first state title, defeating Missoula Big Sky 6-3. In Kalispell, the Flathead boys track team wins a share of the state championship, tying Helena.

Fall 2016: Flathead’s enrollment hits 1,475 and Glacier’s is 1,345, ranking as the eighth and ninth largest schools in the state, respectively.

Oct. 4, 2016: Kalispell voters overwhelmingly approve a pair of bonds for $54 million to build a new elementary school and upgrade other school facilities across the district. Flathead will receive $19 million worth of upgrades and renovations.

Feb. 11, 2017: Flathead wins the wrestling state championship, its first since 2010.

March 11, 2017: With a 46-42 win over Bozeman, the Glacier boys basketball team wins the school’s first state championship.