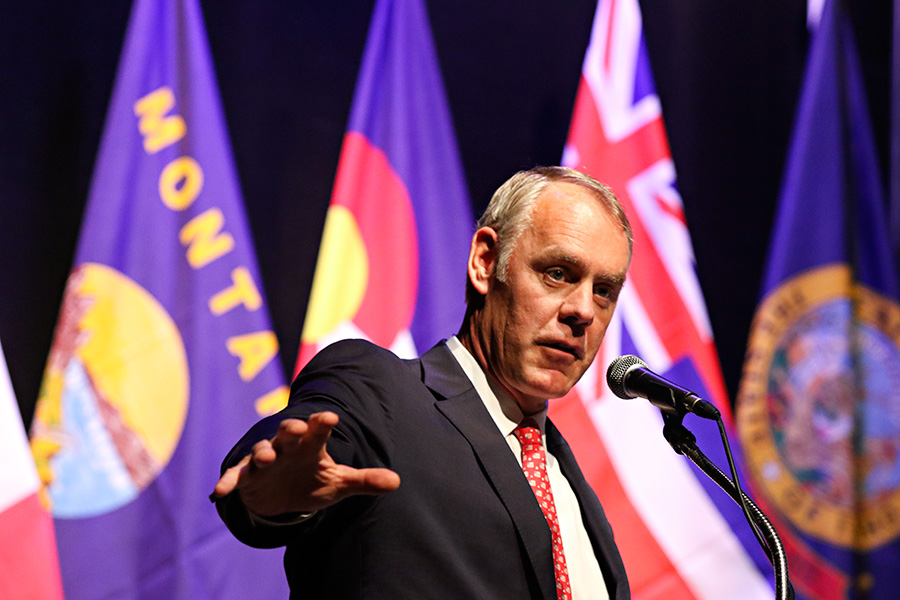

Zinke Recommends Changes on Some Protected Public Monuments

Zinke said unspecified boundary adjustments for some monuments will be included in the recommendations

By MATTHEW BROWN & BRADY McCOMBS, Associated Press

BILLINGS — Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke announced Thursday he won’t seek to rescind any national monuments carved from the wilderness and oceans by past presidents. But he said he will press for some boundary changes and left open the possibility of allowing drilling, mining or other industries on the sites.

Twenty-seven monuments were put under review in April by President Donald Trump, who has charged that the millions of acres designated for protection by President Barack Obama were part of a “massive federal land grab.”

If Trump adopts Zinke’s recommendations, it could ease some of the worst fears of the president’s opponents, who warned that vast public lands and marine areas could be stripped of federal protection.

But significant reductions in the size of the monuments or changes in what activities are allowed on them could trigger fierce resistance, too, including lawsuits.

In an interview with The Associated Press, Zinke said he is recommending changes to a “handful” of sites, including unspecified boundary adjustments, and suggested some monuments are too large. He would not reveal his recommendations for specific sites but previously said Utah’s Bears Ears National Monument needs to be reduced in size.

The White House said only that it received Zinke’s recommendations and is reviewing them.

Conservationists and tribal leaders responded with alarm and distrust, demanding the full release of Zinke’s recommendations and vowing to challenge attempts to shrink any monuments.

Gene Karpinski, president of the League of Conservation Voters, called Zinke’s review a pretext for “selling out our public lands and waters” to the oil industry and others.

Jacqueline Savitz, senior vice president of Oceana, which has been pushing for preservation of five marine monuments included in the review, said that simply saying “changes” are coming doesn’t reveal any real information.

“A change can be a small tweak or near annihilation,” Savitz said. “The public has a right to know.”

A tribal coalition that pushed for the creation of the 2,100-square-mile (5,400-sqaure kilometer) Bears Ears monument on sacred tribal land said it is prepared to launch a legal fight against even a slight reduction in its size.

Republican Utah state Rep. Mike Noel, who has pushed to rescind the designation of Bears Ears as a monument, said he could live with a rollback of its boundaries.

He called that a good compromise that would enable continued tourism while still allowing activities that locals have pursued for generations — logging, livestock grazing and oil and gas drilling.

“The eco-tourists basically say, ‘Throw out all the rubes and the locals and get rid of that mentality of grazing and utilizing these public lands for any kind of renewable resource such as timber harvesting and even some mineral production,'” Noel said. “That’s a very selfish attitude.”

Other sites that might see changes include the Grand Staircase-Escalante monument in the Utah desert, consisting of cliffs, canyons, natural arches and archaeological sites, including rock paintings; Katahdin Woods and Waters, 136 square miles (352 square kilometers) of forest of northern Maine; and Cascade Siskiyou, a 156-square-mile (404-square kilometer) region where three mountain ranges converge in Oregon.

The marine monuments encompass more than 340,000 square miles (880,000 square kilometers) and include four sites in the Pacific Ocean and an array of underwater canyons and mountains off New England.

Zinke did not directly answer whether any monuments would be newly opened to energy development, mining and other industries Trump has championed.

But the former Montana congressman said public access for uses such as hunting, fishing or grazing would be maintained or restored. He also spoke of protecting tribal interests.

“There’s an expectation we need to look out 100 years from now to keep the public land experience alive in this country,” Zinke said. “You can protect the monument by keeping public access to traditional uses.”

The recommendations cap an unprecedented four-month review based on a belief that the 1906 Antiquities Act had been misused by presidents to create oversized monuments that hinder energy development, grazing and other uses. The review looked at whether the protected areas should be eliminated, downsized or otherwise altered.

The review raised alarm among conservationists who said protections could be lost for ancient cliff dwellings, towering sequoia trees, deep canyons and ocean habitats.

Zinke previously announced that no changes would be made at six of the 27 monuments under review — in Montana, Colorado, Idaho, California, Arizona and Washington.

In the interview, Zinke struck back against conservationists who had warned of impending mass sell-offs of public lands by the Trump administration.

“I’ve heard this narrative that somehow the land is going to be sold or transferred,” he said. “That narrative is patently false and shameful. The land was public before and it will be public after.”

National monument designations are used to protect land revered for its natural beauty and historical significance. The restrictions aren’t as stringent as those at national parks but can include limits on mining, timber-cutting and recreational activities such as riding off-road vehicles.

The monuments under review were designated by four presidents over the past two decades.

Zinke suggested that the same presidential proclamation process used to create the monuments could be used to enact changes.

Environmental groups contend the Antiquities Act allows presidents to create national monuments but gives only Congress the power to modify them. Mark Squillace, a law professor at the University of Colorado, said he agrees with that view but noted the dispute has never gone before the courts.

Conservative legal scholars have come down on the side of the administration.

No president has tried to eliminate a monument, but some have reduced or redrawn the boundaries on 18 occasions, according to the National Park Service.