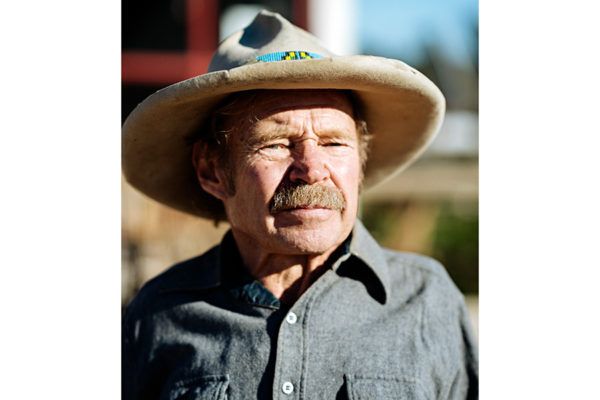

Anyone who knew John Frederick is mourning the passing of a man who stood out as a pillar of the North Fork, the wild and scenic river corridor tracking the boundary of Glacier National Park, where he played prominent roles as affable innkeeper and ardent activist, a pioneering preservationist and honorary mayor who fought mightily to protect a place that captivated him for more than four decades.

By all accounts, he succeeded.

Frederick died Nov. 15 after a long struggle with bladder cancer. He was 74.

In the days following his death, friends and neighbors have reflected on his legacy as the unofficial “Mayor of Polebridge,” a well-deserved honorific that won’t soon be bestowed elsewhere as Frederick’s spirit presides over his beloved community and the environmental safeguards he fostered.

Born in Columbus, Ohio, in 1943, Frederick graduated with a bachelor’s degree in English from The Ohio State University. He served in the U.S. Army from 1966 to 1969, stationed for almost two years in Alaska.

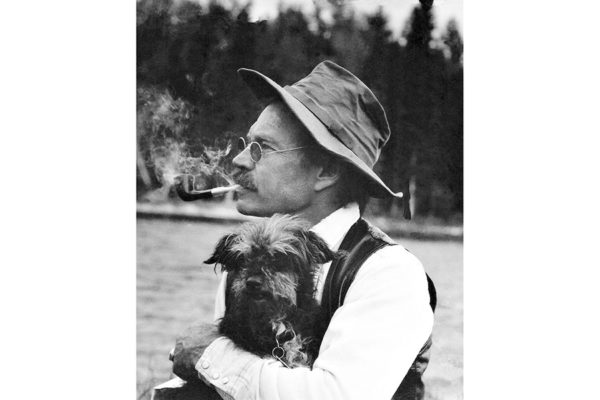

A fervent wilderness advocate, Frederick arrived in Montana in 1976, a pony-tailed back-to-the-lander seeking wild and rustic country and simple living, which he found in Polebridge, the tiny northwoods outpost situated well beyond the terminus of power lines and pavement, after the trappings of modern civilization have receded and the grizzly bears begin to outnumber the year-round residents — home to a saloon and a mercantile and, for the last 40 years, a charismatic, soft-mannered and sometimes crotchety gatekeeper.

In 1978, after living in Olney and later on Rogers Lake, Frederick and his future ex-wife bought a ramshackle cabin on 2.5 acres in Polebridge, paying a song at $39,000 and converting it into the North Fork Hostel, also known as the Square Peg Ranch, which he managed with welcoming grace for nearly 30 years, furnishing travelers from around the world with comfortable and hospitable quarters, and providing a popular gathering place for North Fork events.

The roster of quirky, curious guests who visited Frederick at his hostel grew to biblical lengths.

There was David Mech, the wolf biologist who spent months on end howling for wolves as scientists strove to trace the endangered animals’ resurgence. He occupied one of the hostel’s cabins, which was equipped with a lumpy, button-pocked mattress. When the biologist cleared out, Frederick learned of his nightly discomfort, and from then on he took care to spend one night a year sleeping on each of the hostel’s mattresses in order to ensure his guests’ quality slumber.

Another of the hostel’s inveterate itinerants is Oliver Meister, a German-born traveler who in 1991 was crisscrossing the globe, a seasoned hostel habitue who upon visiting Polebridge was immediately mesmerized by the North Fork.

“I came to stay for a night 26 years ago, but instead of spending a night I ended up spending the whole summer,” Meister recalled. “John kind of took me under his wing.”

Thus began a perennial pilgrimage that drew Meister back to Polebridge every summer year after year, trading room and board for a few months’ labor under Frederick, who compensated the backpacker with untold treasures, introducing him to the vast wilds of the North Fork Flathead River and Glacier National Park, and unlocking the magic of the Whitefish Range.

“He gave me odd jobs here and there and I worked for my stay,” Meister, who grew up near the Black Forest of Germany, said. “But he introduced me to the mountains. I did the tourist things in the park, but John was the one who really opened up the Whitefish Range to me. He let me tag along.”

Meister moved to Polebridge permanently on Nov. 15, 2002, exactly 15 years prior to Frederick’s death, arriving on an immigrant visa that his friend and hostel boss was instrumental in helping him procure.

“He picked me up at the airport,” Meister said. “I worked for him for the next five years.”

Until 2007, when he bought the place from Frederick.

“John always said that he tricked me into buying the hostel,” Meister said.

After a lifetime of travel, Meister, like Frederick, had discovered a place all unto its own. Why travel, they reasoned, when in Polebridge and at the hostel, the world comes to you?

But beyond the walls of the hostel, life up the North Fork kept Frederick plenty busy as he came to occupy a role as its staunchest guardian.

In 1982, he founded the North Fork Preservation Association to advocate against paving the North Fork Road and to promote protection of the North Fork Flathead River, which was threatened by proposed coal mining operations in the Canadian Flathead. He served as president of the organization for nearly 30 years.

Annual NFPA meetings became a fixture of the North Fork’s suite of summer fare, drawing interesting and educational speakers. The NFPA also supported extensive trail maintenance and fire lookout preservation in the Hungry Horse Ranger District, as well as preservation of the Kishenehn Ranger Station in Glacier National Park.

He also served on the board of directors of the North Fork Improvement Association, was a member of the North Fork Land Use Advisory Committee and a board member of the former Glacier National Park Associates. He served on the board of Headwaters Montana for many years, participated in the recent Whitefish Range Partnership, and was a member of numerous conservation associations and initiatives.

In 2014 he received a Conservation Achievement Award from the Flathead Audubon Society in honor of his 35-year effort to keep the North Fork wild. He will be long and well remembered for his soft-mannered yet persistent personality, his wry sense of humor, his dedication to environmental consciousness, and his tireless efforts in the interests of wildlife and wilderness conservation.

And while his respect up the North Fork is well-earned, much of it came with a fight.

When an open-pit coal mine in southeastern British Columbia threatened the Flathead Watershed in the 1980s, Frederick bought stock in the company, Rio Algom, and traveled to Toronto for six years to attend the annual stockholders’ meetings, making motions against the coal mine and effectively derailing it.

“I mean, you can just imagine this little guy from Polebridge, Montana, standing in the midst of all these wealthy stockholders from a big coal company, and he’s reading his proposals to stop the mine, saying that it’s going to ruin the Flathead Basin,” remembers Frank Vitale, whose friendship with Frederick goes back 40 years.

When North Fork neighbors learned that Cenex was planning to drill exploratory wells along the North Fork to search for oil and gas reserves four miles south of Polebridge, near Home Bottom Ranch, Frederick spearheaded the effort to sue the state, arguing that the Montana Board of Oil and Gas violated the Montana constitution’s provision for open meetings, the public’s right to know and its right to participate.

“It changed everything and required a public process,” recalled Roger Sullivan, the attorney who, along with John Heberling, represented the North Fork Preservation Association and the Montana Environmental Information Center in the case. “Today, it’s widely recognized that they have to comply with public participation, open meeting laws and the Montana Environmental Policy Act. That hadn’t been the case up until then.”

The lawsuit forced Cenex to halt production at all of its drilling operations, and a hearing was scheduled for both sides to present findings about the environmental impacts oil and gas drilling would have on the western boundary of Glacier Park.

The hearing was held at the ballroom of the Outlaw Inn in Kalispell and drew 400 people, including out-of-work oil workers from across the state whose careers were in jeopardy.

As the North Fork’s legal eagles called experts to testify about the deleterious effects drilling would have on the region’s pristine natural resources and wildlife species, the oil-and-gas team called Frederick and began inquiring about, of all things, the outhouse he’d built outside his hostel.

“The great outhouse snafu,” Sullivan said. “We were talking about grizzly bears and wolves and the problems that drilling rigs would have on habitat, and they were focused on John Frederick’s outhouse.”

Today, oil and gas leases have been retired and permanent protections that prohibit development are furnished on the North Fork Flathead River.

“I think it is fair to say that because of the efforts of John Frederick the North Fork is one of the few areas that I don’t think will ever be developed for minerals or oil and gas,” Sullivan said. “That is part of John’s legacy. We would not be here without him.”

His clashes with North Fork Landowners Association President Larry Wilson, an opponent of new wilderness whose tenure in the North Fork runs 66 years, were legendary, even as the two men, who were as far apart on the land-use spectrum as two people can be, managed to find a middle ground and developed an abiding if adversarial friendship.

Their famous feuding frequently set the tone at local NFLA meetings to determine the future of development along the North Fork, with the arguments between pro-planning Frederick and property-rights impresario Wilson often threatening to come to blows.

But as the gatherings in the low-slung community building came to a close, the men would reveal they’d carpooled to the meetings together.

“That was John,” Meister said. “He was a character and he always had something up his sleeve. He was kind of like a light. He had a way of looking at the world where there was always a solution, and he helped lead people in that direction.”

Vitale was vice president of the North Fork Preservation Association for 25 years, serving alongside Frederick. He recalls a man whose command of a situation and whose ability to build trust was instrumental in raising issues to the fore.

“With John’s passing I think it’s kind of the end of an era for conservation in the Flathead Basin, and particularly the North Fork,” Vitale said. “John was probably the first really serious conservationist that came to the North Fork and brought all these issues to the surface. Even people who had been there for a long time hadn’t thought of the consequences.”

Most recently, Vitale worked with Frederick and Wilson and a diverse group of stakeholders and competing interests to thrash out the details of a proposal that covers a vast chunk of the Whitefish Range, coming together on a proposed management plan for 300,000 acres of Flathead National Forest.

Vitale joined Frederick, Wilson and former Secretary of State Bob Brown on a mule ride deep into the Whitefish Range, to the top of Mount Thompson-Seton to observe the new wilderness designations and roadless areas brought under the plan.

At the time, Frederick was in terrible pain, suffering from rheumatoid arthritis, and Vitale knew it would likely be his last ride. But the men had spent decades volunteering to clear the trail to Thompson-Seton and save the area, and he was determined that Frederick see the space they’d worked to protect one last time.

“It was important to me that he was on that ride and that he made it up and down that mountain safely,” Vitale said. “It was important for me that he got to see it. And that ended up being his last ride.”