Up the Great Divide

The National Trails System celebrates 50 years as one of the greatest innovations in American outdoor recreation history: the long-distance hiking trail, including the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail, 750 miles of which run through Montana

By Clare Menzel

Dan “Disco” Fenn woke up in a wet tent. An overcast September sky spit a fine, misty rain onto his back as he hunched over a breakfast of Grape Nuts cereal and powdered whole milk. Then he and his partner started walking toward Canada.

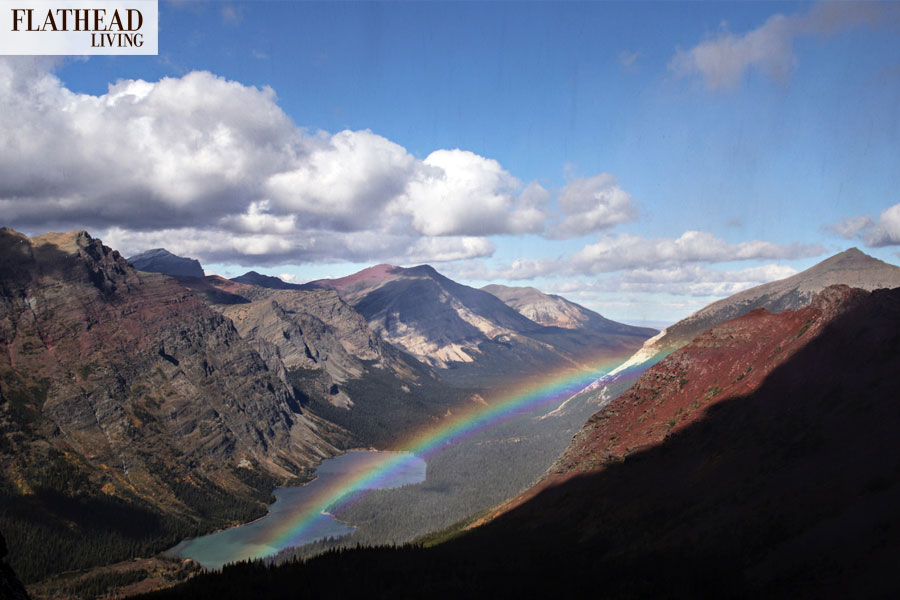

Since departing in April from New Mexico’s Crazy Cook Monument, the southern terminus of the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail, the two hikers had rambled almost 3,100 miles toward Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park. On their final push, they wouldn’t cross paths with the actual principal hydrological divide of the Americas. It juts down from Mount Kip just south of their camp at Fifty Mountain Meadows, then travels over West Flattop Mountain toward the North Fork’s Livingston Range. They would follow the tread up the gut of Waterton Valley, to the border crossing and to the end of America’s fifth-longest long-distance trail.

On the muddy path, Fenn settled into a familiar walking meditation. He first began backpacking in the 1970s, after a National Geographic book on the Appalachian Trail captured his imagination. But between work and family, he never thought he’d have the time for a thru-hike so epic and requiring so much commitment. Stretching between the Canadian and Mexican borders, the Continental Divide Trail connects five states, 25 national forests, 21 wilderness areas, three national parks, eight Bureau of Land Management resource areas, and a national monument. Its many miles are maintained through the collaboration of every land management agency and by an army of volunteers — including Fenn, who would start coming back to Montana to volunteer on trail projects in the years following his 2010 hike.

When Fenn and his partner reached the modest obelisk marking the conclusion of their trek, they cracked open miniature bottles of champagne and bourbon. After a half-year on the trail, it didn’t take much for the backpackers to earn a happy buzz. As they celebrated, they joked that they wished they had booked a ride on the boat that whisks visitors across Waterton Lake to the park townsite, to the car, to home. It was still rainy, and they were tired.

The majority of Continental Divide Trail hikers travel northbound to the Canadian border, kicking up dust in the warming springtime Southwest, smelling Colorado’s alpine wildflowers at high bloom, and then welcoming autumn in Idaho and Northwest Montana. After a few thousand hard miles, Glacier National Park is the victory lap.

“Once you get to the Bob [Marshall Wilderness], you’re almost there,” Fenn said. “You go through Glacier, which is just spectacular. You look back at where you started, at the Mexican border, flat as a pancake and dry … Boy, I tell you, there’s not much to compare [Glacier] to. You go out on a big note.”

For Fenn, it was the grand finale. He had raised a family in Coxsackie, New York, and served in the United States Navy for 30 years, as well as in the civilian workforce. The “hiking bug,” as he said, itched at him ever since his days at the Naval Academy. In 2001, he quit his job at a security firm to hike the 2,189-mile Appalachian Trail. Again in 2007, he quit his job to hike the 2,654-mile Pacific Crest Trail. By 2010, he was prepared for the Continental Divide Trail.

Fenn says the Continental Divide Trail “has a reputation of being the wildest, most out-there, and the ruggedest” of what’s known as the “Triple Crown.” Fewer than 300 hikers have officially completed this trifecta, which represents the best of American long-distance hiking. It includes the East Coast Appalachian Trail, the West Coast Pacific Crest Trail, and the Rocky Mountain Continental Divide Trail. Totaling approximately 7,900 miles altogether, these trails also share protections by the National Trails System Act, which was written into law in 50 years ago in 1968.

“The modern hiking trail is an uncanny thing,” observed Robert Moore in his recent book “On Trails,” a philosophical treatise on trails and his experience thru-hiking the Appalachian Trail. “We hikers generally assume it is an ancient, earthborn creation — as old as dirt. But in truth, hiking was invented by nature-starved urbanites in the last three hundred years.”

In the 18th century, the word “wilderness” had a different meaning than it does today, as environmental historian William Cronan contends in his essay “The Trouble with Wilderness: Or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature.” Wilderness did not relate to pristine beauty or natural splendor; it was more closely synonymous with “desolate,” “barren,” and “anything but positive,” Cronan wrote. “And,” he continued, “the emotion one was most likely to feel in its presence was bewilderment — or terror.” Only in the late 1800s did Henry David Thoreau declare that mankind needs the “tonic of wilderness” and did the nation start drawing lines around massive stretches of wild public land — the Yosemite Act of 1864, protecting the valley from settlement, led to the 1872 establishment of America’s first national park, Yellowstone.

The idea for a long-distance trail apparently struck 21-year-old hiker Benton MacKaye while on a walk in the Green Mountains of Vermont in 1900. From a dramatic vantage point, he “suddenly envisioned a single trail stringing together the entire Appalachian range from north to south,” Moore wrote. The footpath he imagined would be composed of many connected segments, each maintained by local organizations. This “utopian” idea was seen, at first, as a “damn fool scheme,” Moore reported. Yet, “a new conception of trails was spreading. Trail designers began to reconsider the isolated clusters of trails that had once surrounded the most popular hiking destinations and discovered ways to connect those clusters into cohesive networks. Soon, there arose the notion of a ‘through trail’ — a trail that would keep going.” By 1925, MacKaye, who later became a forester and regional planner, garnered enough support to form a conservancy of hikers. In 1937, the Appalachian Trail, from Maine to Georgia, was completed.

In 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson wrote to Congress that, even though “nature’s beauty must be a “part of our daily life … More of our people are crowding into cities and being cut off from nature.” He believed that if the American people were to conserve wild lands, the “protection and enhancement of man’s opportunity to be in contact with beauty must play a major role” in that effort. He went on to request that the Secretary of the Interior create a national system of trails reaching more than 100,000 miles in total. “In the back country,” he wrote, “we need to copy the great Appalachian Trail in all parts of America.”

The shifting tide of opinion toward wilderness was rich with moral overtones. Nature was increasingly seen as an antidote to the evils of a technological, fast-paced, and urban society. It became a place for redemption and chance encounters with the divine. For one, MacKaye believed his trail was “a moral equivalent to war.” A “prime national goal,” President Johnson wrote in his letter to Congress, “must be an environment that is pleasing to the senses and healthy to live in.”

“The beauty of our land is a natural resource,” the president stated. “Its preservation is linked to the inner prosperity of the human spirit.”

In December 1966, the Department of the Interior submitted to Congress the Trails for America proposal, noting that the “expressed desire [for hiking trails] surpasses existing opportunities.” The meat of the document outlined a number of national scenic trails and metropolitan area trails, including one that would pass through “some of the most scenic areas in the country” along the Continental Divide. The idea for this trail, the proposal mentioned, had come from a group of horsemen known as the Rocky Mountain Trails.

On October 2, 1968, the National Trails System Act was signed into law. It added the existing “super trail” of the Appalachian Mountains to the new system and established the Pacific National Scenic Trail. In 1987, the National Parks and Recreation Act officially brought the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail into the system. Since then, the trail network has grown to include 20 national footpaths, including the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail, which reaches from the “Plains to the Pacific” and passes by Browning. The Continental Divide Trail is still the youngest, highest, and most remote of the National Scenic Trails.

Fenn says he didn’t often consider the legal status of the trail when he was on it, but he’s “thankful that, back in the day, or even currently, the powers that be see fit to legislate these National Scenic Trails such that some of our wilderness areas are preserved for future generations.”

Approximately 750 miles of the Continental Divide Trail run through Montana, starting at West Yellowstone. From there, it bounces across the Idaho-Montana border, passes through the Anaconda-Pintler Wilderness, threads the needle between Butte and Helena, and then aims for the Scapegoat and Bob Marshall Wildernesses and the Lewis and Clark National Forest. The final brush with full-blown civilization is the pitstop in East Glacier, where Brownie’s Hostel welcomes many thru-hikers.

Per the trail’s “comprehensive plan,” the tread travels as close to the geographic Continental Divide as possible, cutting away only to provide for safe travel, recreational appeal, economic feasibility, and to mitigate environmental impacts. It is technically just 85 percent completed, according to the Continental Divide Trail Coalition, meaning it occasionally requires route-finding as well as walks along U.S. Forest Service roads and even highways. As Moore wrote, “The task of creating a super-long trail principally consists not of trail-building but trail-linking.”

Between 100 and 200 hikers walk between Mexico and Canada each year. It’s quiet on the tread, with much less traffic than the Appalachian and Pacific Crest Trails, which are visited by thousands. It often draws hikers who have completed other long-distance treks and are ready for a new challenge. There are those like Fenn, who wait and scheme for years to fit the puzzle pieces together. There are also the young and the bold.

Garrett “Uncle Gary” Lane, a big-bearded, Whitefish-based wildland firefighter, walked the Pacific Crest Trail in 2010. Though he had camped before, the well-marked, meticulously maintained trail was his introduction to backpacking. After watching a documentary about the Continental Divide Trail, he quickly began planning a trip. As a trail crew laborer at the time, he says he didn’t have anything to tie him down, like house payments or a dog. “Why don’t I just do this?” he thought. He completed the northbound Continental Divide Trail in 2014. Like Fenn, he relished the experience of finishing in Glacier National Park — he’d been talking it up to his partners the entire trip: “Glacier is going to blow your mind.”

“There’s something cool and special that people had the forethought to put together this incredible journey,” Lane said. “That people had the foresight to designate a path from point A to point B, that you can walk from one border to another, that you can walk across this country and mostly be on trails on public land. There’s value in being able to set out and just walk. With the digital world that everyone’s so wrapped up in, it’s nice to know if you want to go walk for five or six months, there are paths in this country.”

Continental Divide National Scenic Trail

3,100 total miles

750 miles in Montana

2,150 miles in National Forests (the U.S. Forest Service officially administers the trail, since it oversees the greatest mileage)

275 miles in National Parks

110 miles in Glacier National Park

14,270 feet — highest point, Gray’s Peak, Colorado

4,200 feet — lowest point, Waterton Lake, Montana

Triple Divide Peak — here, on the East Side of Glacier Park, two separate continental divides cross, sending water to the Pacific, Atlantic, and Arctic Oceans

1,000 feet — average height of the Chinese Wall, a striking lime escarpment in the Bob Marshall Wilderness

17 miles per day — the average mileage covered by a thru-hiker

1930 — first documented thru-hike of the proposed Continental Divide Trail, by David Maceyka and a crew from the Rocky Mountain Trails Association

The Blue Can Trail — what Maceyka called the trail, referencing the blue cans that the crew nailed to the trees to mark the route for U.S. Forest Service workers

85% of small business owners near the trail said that “protecting, promoting and enhancing the Continental Divide Trail is important to the well-being of businesses, jobs and their community’s Economy” (Continental Divide Trail Small Business Survey, Continental Divide Trail Coalition)

ROOM WITH A VIEW: STAY AT THE GRANITE BUTTE LOOKOUT TOWER

The Granite Butte Tower overlooking Stemple Pass in the Helena-Lewis and Clark National Forest is the only lookout perched on the Continental Divide crest. It sits approximately 16 miles southeast of Lincoln on a grassy ridge at 7,587 feet, directly on top of the divide. First built in 1932 and reconstructed in 1962, it fell into disrepair until more than 50 volunteers with the Montana Wilderness Association brought it back online in 2016. Crews also built three miles of new trail around Granite Butte, establishing it as an accessible destination for hikers. Enjoy the wood stove during colder months and 360-degree views from the wraparound porch year-round. To reserve, visit recreation.gov.

SECTION HIKES IN GLACIER NATIONAL PARK

1. Swiftcurrent Pass: Start at Many Glacier. Hike along Swiftcurrent Creek, up the dramatic wall of the pass, and peek over into the West Side of the park. Stop by the Granite Park Chalet, or continue up to Swiftcurrent Lookout for a higher vantage point.

2. Northern Highline: Start at the Loop, and hike up to Granite Park Chalet. The Continental Divide Trail comes from over Swiftcurrent Pass. Pick it up on the Northern Highline trail, traveling north to Granite Park Campground. Hike as far as you like before turning back — Ahern Overlook, with views into the Belly River, is a great destination. Or continue to Fifty Mountain Meadow and stay the night before returning.

3. Dawson-Pitamakan Rising Wolf Mountain Loop: Start at Two Medicine and travel along the Pitamakan Pass Trail. A few miles in, the Continental Divide Trail will join and then branch off after Pitamakan Pass. Continue on to Dawson Pass and back to your starting point at Two Medicine for a big, round-trip day hike.

4. Triple Divide Pass: Start at Cut Bank and hike up the Pitamakan Pass trail. Bear right to follow the trail climbing the flank of Mount James toward Triple Divide Pass. Turn back for an in-and-out day hike, or continue over the pass toward the Red Eagle Trail and St. Mary for a multi-day backpacking trip.

5. Many Glacier to Chief Mountain Customs: Start this multi-day hike at Many Glacier. Travel up and over Swiftcurrent Pass, then along the Northern Highline and into the Waterton Valley. Take the right-hand turn leading up to Stoney Indian Pass, then travel into the Belly River toward Glenns and Cosley Lakes. Follow the trail all the way to the Canadian border.

Read more of our best long-form journalism in Flathead Living. Pick up the spring edition for free on newsstands across the valley.