Land and Labor: The Siderius Legacy

At age 86, more than 50 years after making front-page headlines by rolling a 25-ton bulldozer off Going-to-the-Sun Road 350 feet down a mountainside, Charles Siderius still shows up for work each day

By MYERS REECE

Two years ago, when Charles Siderius was just an 84-year-old spring chicken, he was toiling in the fields on the family farm east of Kalispell, working as hard as he had for more than seven decades. He felt a strange sensation, nothing scary, just different. He told his son, Dan: “There’s something wrong with me.” Then he pinpointed the feeling.

“I’m tired,” he said.

“Well,” Dan replied, “you’re old.”

The elder Siderius contemplated that for a minute and went through a mental checklist of his friends who were now living in Immanuel Lutheran Communities, a residential complex for senior citizens.

“I guess most everybody is in the Lutheran home,” he acknowledged. “Maybe I am old.”

Then he went back to work. It’s the Siderius way, the only one he knows.

Charles Siderius is the eldest of six siblings and one of the oldest living members of the sprawling and influential Siderius clan, who meet frequently for huge family reunions that host up to 250 relatives and are funded through a family trust reserved exclusively for that purpose.

“When we have a family reunion,” Dan says, “it takes a day or two just to figure out who everyone is.”

Charles’ father, Pete, was the second of 13 children born to Evert and Gertrude Siderius, the earliest Siderius settlers in the Flathead Valley, arriving in 1908 with six children. Evert and Gertrude were both born in Holland and lived in Michigan before moving to Montana. In 1917, the family purchased 240 acres south of town for $10,000, the start of 100 years of Siderius land ownership and farming in the valley, including hundreds of acres permanently protected in the last decade by conservation easements along the Flathead River.

Pete, the oldest boy, worked on the farm, in logging camps and did other jobs to help out the large family until starting at the Somers tie plant, where he bucked ties for 25 years. Charles was Pete and Louise’s first child, born in 1931, and he took on many of the same oldest-son responsibilities as his father had growing up. That’s when he learned to work hard, as an unquestioned way of life, a hard-nosed philosophy that hasn’t waned over the decades.

“He kinda runs the show,” Ken, a younger brother, said of Charles. “If someone needs a hand, he’s there to help them. He knows what the hell work is.”

When Charles was in his mid-20s, he was working with his uncle Johnny Paola building road for the J. Neils Lumber Company when he caught wind of a Cat bulldozer for sale. Ready to take on his own roadwork, Charles zeroed in on buying the Cat, the essential tool for the job, although there was one problem: he couldn’t afford it.

He asked his father if he could have $5,000, and Pete agreed. It wasn’t until years later, while sifting through W-2s, that Charles discovered his dad only made $4,200 a year. Without hesitation, he had given his son more than a year’s worth of hard-earned, tie-bucking money. Pete saw it as an important opportunity, and Charles didn’t let him down.

“That’s how I got my start,” Charles said.

In the fall of 1958, Charles got a job building logging roads in Idaho, followed by other contracts doing the same work in the greater Flathead Valley. He built miles and miles of access roads for timber companies over the years, including a gig for the American Timber Company in the early ‘60s. When Charles brought up contract details with Hans Larson, American Timber’s founder, Larson brushed him off.

“He said, ‘If I can’t take your word on a handshake, what good’s a piece of paper?’” Charles remembers Larson telling him. “I never forgot that.”

Charles built up his business and reputation over the years, branching out into logging as well as road-building, but no job left an impression quite like plowing Going-to-the-Sun Road in Glacier National Park. In the early 1960s, that size of machinery hadn’t ever been used before on the winding, narrow road, which can be buried by snow as high as buildings.

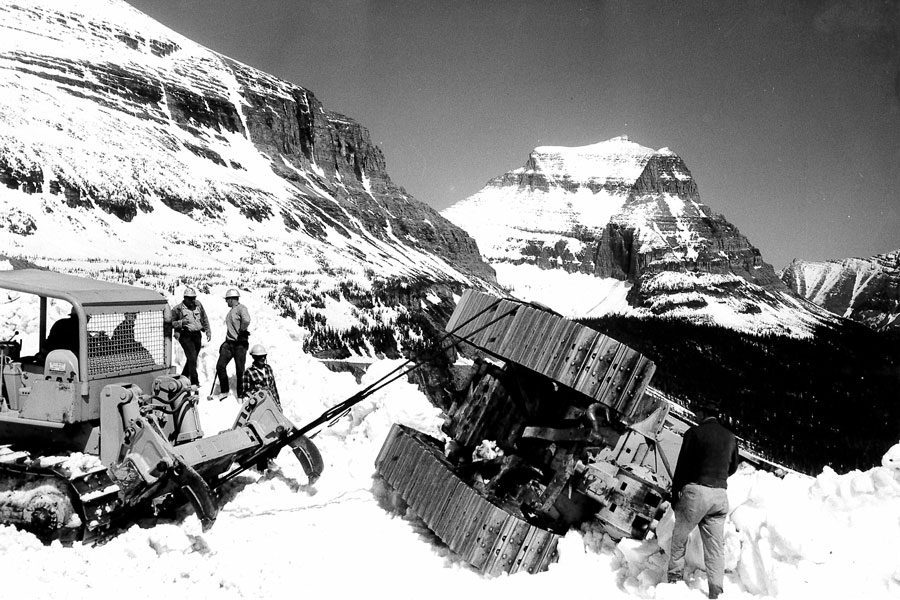

On Memorial Day weekend in 1964, Charles was one of four plow operators, including his brother Tom, clearing snow on the Sun Road. As Charles worked on a 70-foot-deep drift, he heard a sudden noise that sounded like a rifle shot. It was a three-foot-thick slab of snow, an acre wide, breaking loose underneath his 25-ton bulldozer.

Tom watched in horror as his brother’s hulking D-8 dozer plunged down the steep mountainside, rolling seven times, each bounce covering about 50 feet. The machine finally came to a rest 350 feet below the road, upside down and the engine still running, with Charles pinned to the roof underneath heavy snow.

Park foreman Claude Tesmer got down the mountain first and found a single hand poking out of the snow. Then he heard Charles say, “Get the snow off my head so I can breathe,” as recounted in a June 5, 1964 front-page Hungry Horse News article by Mel Ruder. The Wall Street Journal also later wrote about the incident.

Rescue teams lowered a basket down the steep mountainside to retrieve Charles, while a dozer winch pulled the Cat back to the road. Somehow, Charles suffered only one or two cracked ribs and bruises. As he acknowledges, he was lucky.

“My whole life passed before my eyes,” he recalled recently. “I don’t know what I thought about. I guess I thought about a lot of things.”

Charles understandably wasn’t as enthused about plowing in Glacier Park after the accident, but his enthusiasm for operating big Cats in the woods continued throughout his career and was passed down to his children. Dan runs a construction and excavation business and builds logging roads, although there are far fewer these days.

One of the 1960s dozers from the Going-to-the-Sun days is still operable, sitting on the property waiting to be called into action. But Charles doesn’t wait around for work; he goes and finds it, whether it’s in the woods or on the farm or in whatever venture he has taken on over the years. His children — Dan, LeAnn, Laurie and Doug — inherited those values from their father, and they recall always trying to stay busy as kids, preferably out of Charles’ sight, because if he found them lazing around, he’d put them to work.

“That’s one of the things he really instilled in us: a work ethic,” daughter LeAnn Siderius, a local real estate agent, said.

Doug also runs a construction and excavation business and owns the Blaine Creek Grille, his first foray into the restaurant business. Dan says that’s another defining feature of their father: he supports any reasonable idea his children have, whether he relates to it or not, the restaurant being an example.

“He’s always optimistic,” Dan says. “That’s why he did so well. He was never afraid to take a chance. He always encourages us. He’ll say, ‘Well, do it if you have a plan.’”

Charles has been similarly impactful on his siblings, a patriarch of sorts but also a friend and mentor.

“He’s a great brother,” Ken says.

Even as Charles enters his late 80s, a visitor shouldn’t be surprised to find him chugging around in a tractor under the hot summer sun, putting in long hours when he could be enjoying retirement. But don’t ask him to use the tractor’s new-fangled GPS. Even Charles Siderius has his limits.

Read more of our best long-form journalism in Flathead Living. Pick up the summer edition for free on newsstands across the valley.