Investors Bring Economic Diversity to Libby Industrial Park

Local stakeholders are working in a public-private partnership to redevelop the Kootenai Business Park and Superfund site where widespread asbestos contamination has hindered economic development in recent years

By Maggie Dresser

On a sunny March afternoon, Gloria Byrnes arrived at Clark’s Courts, a new pickleball facility on the southeast edge of Libby in the Kootenai Business Park, to participate in a free introductory class. She also signed up for a membership and thanked the owner for bringing the sport and the facility to the community.

“We need this,” Brynes said. “Pickleball is so fun and I’m not good at it, but I’ve played a couple times … I’m just really happy it’s here.”

Local real estate agent Eric Clark launched the private pickleball court in January after purchasing a few acres from the Lincoln County Port Authority (LCPA) in 2022.

Clark is one of a handful of investors who have recently shown interest in properties available at the industrial park, which formerly housed Stimson Lumber Company before it shut down in 2002.

Born and raised in what was once northwest Montana’s industrial hub, Byrnes remembers swimming in the nearby creeks and tributaries of the Kootenai River, hiking in the Cabinet Mountains and learning to ski when Turner Mountain opened outside of Libby in 1960. She later went on to work at the Stimson Lumber Company on the southern edge of town, a job that she held for years during the height of Montana’s timber years.

“This town was booming when my daughter was in school in the 70s and 80s,” Byrnes said.

In the past few decades, however, Libby’s endured more bust than boom. And while Byrnes has remained in her hometown through one recession after another, including one of the deadliest environmental tragedies in U.S. history, she sees a bright economic future for Libby from where she’s standing today — in the middle of a pickleball court at what could be Lincoln County’s next economic hub.

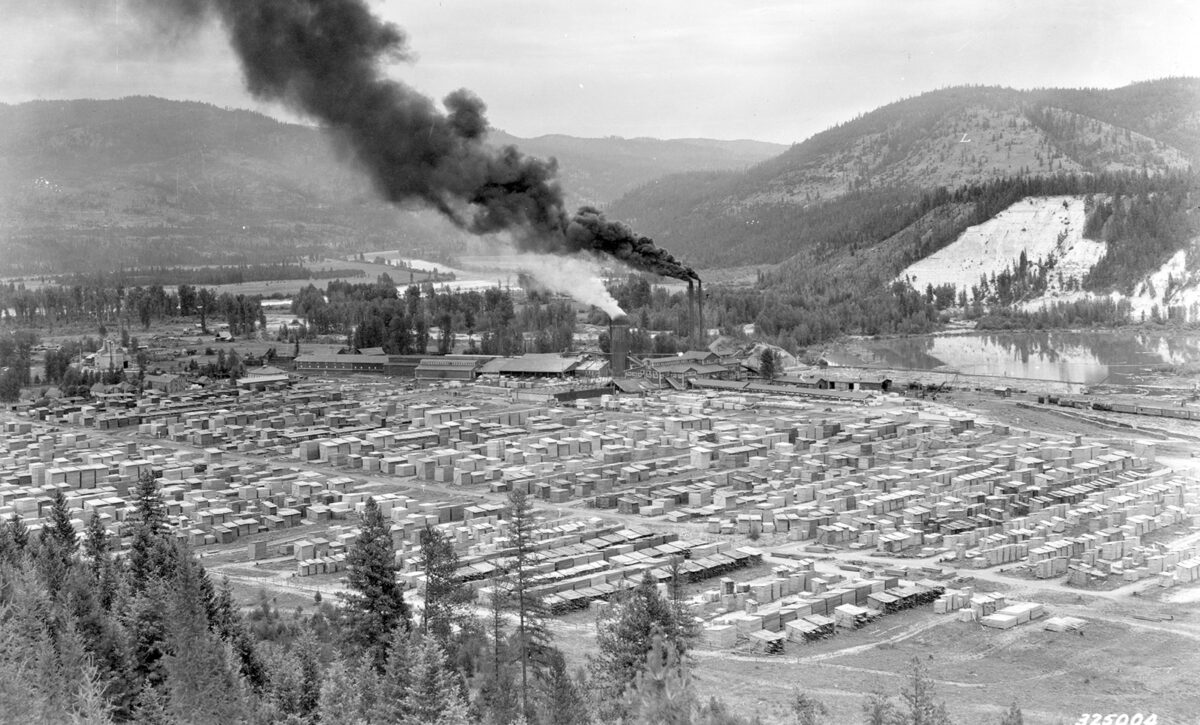

During Libby’s boom, the lumber industry was flourishing and the W.R. Grace and Co. vermiculite mine supplied 80% of the world’s insulation and building supply for 70 years before it shut down in 1990. Stimson Lumber Company had been in operation for nearly 100 years and was Libby’s largest employer before closing in 2002 due to a decline in wood products.

The closures of the mine and the mill were devastating blows to Libby’s workforce, resulting in the losses of hundreds of jobs within a 12-year period in a town with a population that hovers around 2,700 people.

Lincoln County, where the unemployment rates consistently rank among the highest in the state, reached its peak of 29% following the closure of the mine in March 1991, according to U.S. Bureau of Labor and Statistics data. Following the lumber company’s closure at the end of 2002, the unemployment rate rose from 6.7% to 15.8% within six months.

Following the discovery in 1999 that the community was contaminated with deadly airborne asbestos fibers, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency initiated its investigation and removal program in 2000, placing much of Libby on the Superfund program’s National Priorities List (NPL). In an unprecedented step in 2009, the EPA declared a Public Health Emergency in Libby as a measure to provide federal health care assistance for victims of asbestos-related disease.

Occurring amid the backdrop of the Great Recession, the public health crisis hobbled Libby’s economy and fundamentally reshaped its reputation as an industrial hub.

A quarter-century after the asbestos contamination was first discovered and following years of economic downturn, the EPA has removed more than a million cubic yards of asbestos-contaminated waste and the environmental remediation and cleanup is nearing completion. Meanwhile, seven of the eight cleanup areas, designated as operable units (OUs), have been remediated, setting the stage for redevelopment. A second Superfund site in Libby, the Libby Groundwater site, consists of a contaminated groundwater plume that extends underneath the Port Authority property. (To ensure property owners don’t risk exposing themselves or tenants to hazardous materials, or become liable for worsening site conditions, EPA encourages property owners to call the agency prior to excavation.)

Most notable from an economic standpoint is the 400-acre industrial park and former Stimson Lumber property known as OU5, which was delisted from the NPL earlier this year following its remediation in 2016. While most of the cleanup is complete, maintenance is ongoing as federal officials continue working to monitor and mitigate any potential exposure pathways.

Despite the contamination at the industrial park, Libby officials have been working to promote economic activity on the property, which was named the Kootenai Business Park after the Lincoln County Port Authority (LCPA) acquired it in 2002.

Located just southeast of the city’s limits and utilizing municipal utilities, companies like Stinger Welding, which employed 69 people and closed in 2013, failed to prosper in park. The same facility was briefly home to Isotex Health, a hemp processing company that closed in early 2020.

But after a series of business flops at the site over the years, and in light of the recent delisting of OU5, the property has recently become an attractive location for economic development. Investors have already begun planning for new business endeavors on half of the property, which features BNSF railway access, and the public-private partnership is gaining steam. The other 200 acres is already used as a public space with a fishing pond, a radio-control racecar track and a walking trail on the eastern edge.

While county officials and Libby residents want to see another lumber mill operating on the site, they say there’s interest from a variety of companies they hope to bring economic diversity to the park.

For example, Kalispell-based Nomad Global Communication Solutions (GCS) expanded its mobile command center vehicle manufacturing business to the park two years ago with plans to bring more than 100 jobs to Lincoln County. The operation moved into the 100,000-square-foot facility that formerly housed Stinger Welding and Isotex Health.

The Port Authority also recently sold 107 acres to Chris Noble, owner of Noble Excavating and Noble Investment Properties. He’s been working with public agencies to remediate the site with plans to build road infrastructure and demolish multiple buildings, including the Stimson Lumber Company facility.

“I’m a native of here and we just feel confident of our community, and we just want to see it grow,” Noble said.

Tina Oliphant of Noble Investment Properties, who previously worked as the executive director of the Port Authority for several years, says the renewed interest in private investment creates opportunities for retail and commercial businesses in a county with limited private land available for development.

“Noble Investment Properties came in and started negotiating with the Port Authority for acquisition of a portion of the property and after decades of different owners and the lumber mill, there were environmental concerns,” Oliphant said. “So, there’s a tremendous amount of work to turn that land into a site that can be developed.”

“It’s going to bring in a really well-functioning and attractive industrial park and delivery to Montana with nice access to city utilities,” Oliphant added.

Former Lincoln County Commissioner Jerry Bennett said the stakeholders envision a variety of small businesses working in the industrial park to diversify the economy.

“When the mill left, it employed 400 people but if we can develop numerous businesses that employ 10 to 20 people with that diversity, it’s far better for Libby than having one industry,” Bennett said. “We still want a mill, and we still want a mine, but that diversity will help Libby’s economy.”

With decades of experience as a heavy civil contractor, Noble’s excavating crews have begun remediating the property and they plan to finish building a new road this year and tear down most of the dilapidated buildings on the property. Stimson’s former central maintenance building, which sits prominently in the center of the site, will be torn down and replaced with a road.

While EPA already delisted the area, environmental cleanup and contaminant testing is ongoing as part of the Brownfields Program, which provides funding for redevelopment on contaminated sites through EPA and the Montana Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ).

“They really want to see Superfund sites redeveloped – that’s their success story,” Oliphant said. “They’ve been very good partners and that’s an important key to being able to get this done.”

On the northwest corner of the property, Clark purchased his postage stamp of property in 2022, but only recently launched his private pickleball venture, dubbing it Clark’s Courts.

As the fastest growing sport in the nation, Clark wanted to bring pickleball to Libby and started renting space at school gyms before he opened the 10,000-square-foot facility next to Libby City Hall.

Although the court is situated at the center of an ongoing construction zone with no heat system installed yet, and an office desk made of stacked plywood serves as its only furnishings, that hasn’t deterred Libby residents like Byrnes from adopting the game with enthusiasm; Clark says he’s already up to more than 40 memberships.

With plans to add four basketball hoops in the facility, a mezzanine floor, commercial kitchens, a pro shop and American with Disabilities Act (ADA) compliant bathrooms, Clark also hopes to build a swimming pool in the next few years.

“I think it was great as far as what the Port chose to do in selling parcels,” Clark said. “Instead of bringing in large corporations that take large portions of property, it allows us smaller investors the opportunity to take little chunks. I think it’s just been great and for me, the property is ideally located … the proximity is wonderful.”

Clarification: This story has been updated to make clear that, while all operable units aside from the former vermiculite mine site have been remediated, two residential operable units in Libby remain on the National Priorities List. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency anticipates proposing those for deletion from the NPL following the next five-year review evaluating if the remedy is continuing to protect human health and the environment.