Public Interest in CFAC Superfund Intensifies as Development Plans Emerge

With a renewed degree of community attention on the proposed federal cleanup plan, environmental regulators are ramping up outreach efforts and providing funding for a grassroots coalition to hire independent technical experts

By Tristan Scott

Last year, when the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) released its proposed cleanup plan for the Columbia Falls Aluminum Company (CFAC) Superfund site, project managers considered it a success if nine people turned up at a community engagement meeting. On Wednesday evening, attendance swelled to nearly 90 residents who crowded a conference room in downtown Columbia Falls to learn about the proposed federal cleanup action on the contaminated property near the Flathead River.

The meeting stretched to more than three hours as community members posed questions and raised concerns about the agency’s preferred remediation plan, which has yet to be approved, including future ecological risks and threats to human health and safety. Earlier in the day, Matt Dorrington, the EPA’s remedial project manager for the CFAC Superfund site, said he fielded questions from about 45 additional residents who trickled in throughout the afternoon during an open-house style engagement session.

“I’ve spent all day talking and my legs and knees are killing me but it’s exciting,” Dorrington said. “I’m excited about the renewed interest and that’s what we’re responding to.”

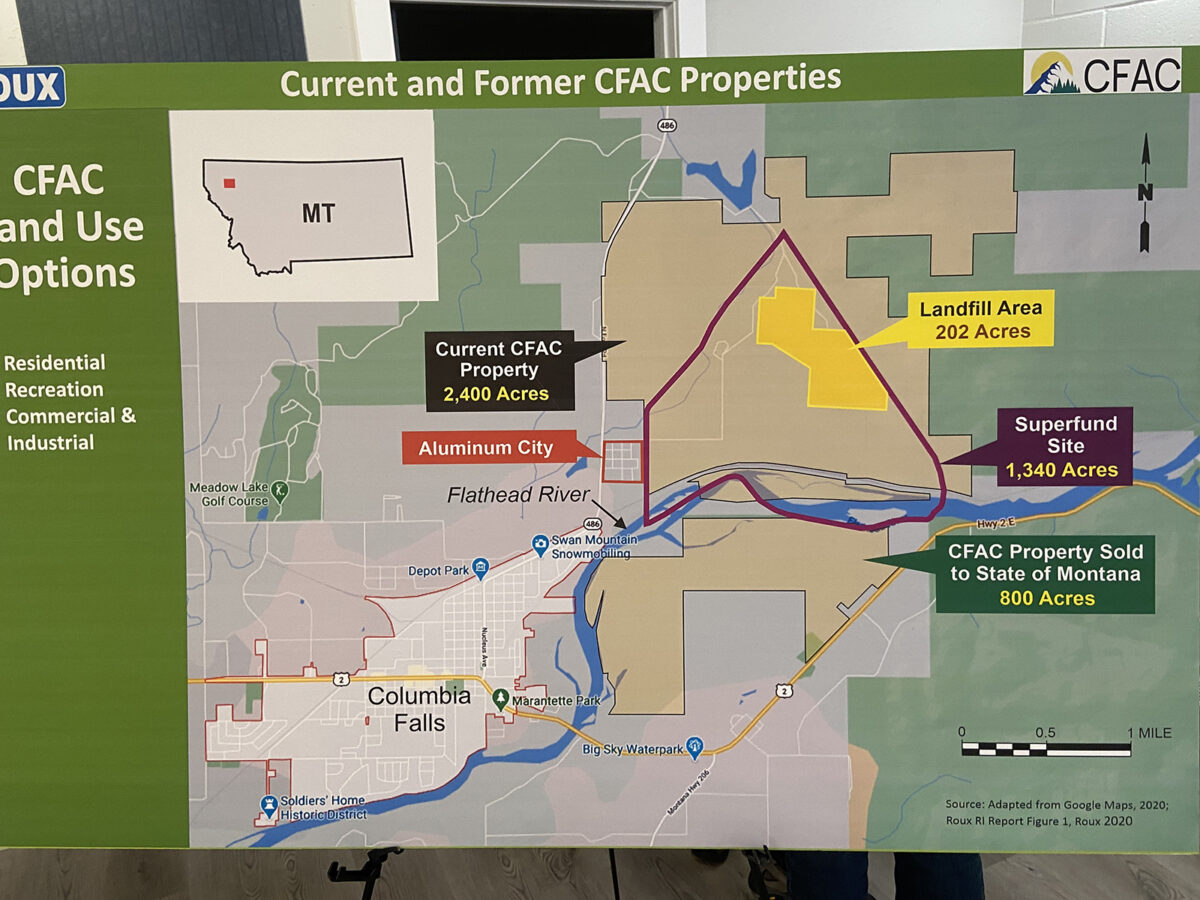

On Thursday, Dorrington was prepared to repeat the process of responding to the community, which also provides the project manager with an opportunity to clarify some misinformation that’s emerged in recent weeks after the owner of the Superfund site, Glencore, publicly announced plans to sell 2,400 acres to Ruis Construction owner Mick Ruis for residential and commercial use. While the terms of the sale are confidential, the deal is contingent on EPA finalizing the details of its proposed cleanup plan by issuing a Record of Decision.

“What Mr. Ruis decides to do after he buys it will be his business, not ours,” CFAC Project Manager John Stroiazzo told the audience. “We’re just going to sell it and it’s going to comply with the law, it’s going to comply with the regulations. His activities will have to comply with local zoning laws, but he will have multiple options — recreation, residential, commercial, industrial — whatever he chooses. But it’s all dependent on this plan.”

With a vision finally emerging for the sprawling property at the base of Teakettle Mountain that has been dormant since 2009, much of the recent community concern has centered on the EPA’s proposal to contain rather than remove the environmental hazards; specifically, groundwater in the plume core that contain concentrations of cyanide, fluoride and arcenic in dangerous concentrations, posing risk to future residential drinking water users.

That’s a fair point, the project manager concedes, but some of the rhetoric has gone so far as to suggest that EPA passed over that option because it was too cost prohibitive, which conjecture Dorrington said isn’t true; those remediation alternatives were ranked and evaluated in an early screening phase and were ultimately dismissed due to a range of factors, including risk to human health and safety.

“It’s the implementability and effectiveness that moved off-site disposal off the table and from future consideration,” Dorrington said. “There’s an entire page in the proposed plan that talks about all the reasons that off-site disposal is not a good idea. It was talked about and has been talked about at length, so I’m frustrated to hear this discussion come back to costs when that’s never been the agency’s position. That alternative was not eliminated solely because of costs.”

The EPA’s cleanup proposal estimates the cost of off-site disposal as ranging from $625 million to $1.4 billion, compared to the $57.5 million cost of the preferred alternative, which involves capping the site where the highest concentrations of contaminants were detected and sealing it off with what’s called a slurry wall that fully encompasses the West Landfill and Wet Scrubber Sludge Pond, creating a containment cell around the contaminated groundwater plume at the source area. But the agency also evaluated the logistics of off-site disposal, including excavating about 1.2 million cubic yards of hazardous waste from the landfills, which would need to be dewatered and carted off site to the nearest Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) landfill in Arlington, Ore., nearly 500 miles away. The process would require 60,000 truckloads or rail containers passing through 30 neighboring communities en route to the Oregon landfill, including Spokane, Wash. And the Tri-Cities, amounting to 70 trucks or trains per day over the course of four or five years “with associated noise, dust, congestion, traffic issues, and delays from railroad crossings.”

And that’s without considering the health risks to workers loading and unloading trucks with spent potlining — the waste generated at an aluminum smelting facility such as CFAC, and which can react with water to produce toxic and explosive gases — let alone the potential traffic accidents and fatalities likely to occur based on Federal Highway Administration statistics.

“There are serious risks associated with off-site disposal,” Dorrington said. “Now, are they risks that we can mitigate? Sure. But I wouldn’t want my son working on that site.”

Still, even as Dorrington explained the step-by-step process EPA investigators and environmental engineers with Roux Environmental Engineering and Geology took to screen every possible cleanup scenario and all the available technology before settling on its preferred alternative, one persistent question kept rearing its head Wednesday night: What if the containment cell fails? What happens if, in 30, or 40, or 50, or 100 years from now, the slurry wall gives out and the water plume migrates into the Flathead River?

It’s a legitimate question, particularly if one considers that of the 86 instances in which EPA has employed a slurry wall to contain waste at a Superfund site, four of them have failed. But to Peter Deming, a retired consulting engineer with 35 years of experience working on Superfund sites, it’s a question that has much less relevance in the context of today’s remediation technologies for containing contaminants like those detected in CFAC’s groundwater plume.

“We know that this system will not fail,” Deming said.

Jim Peacock, a science teacher at Columbia Falls High School, likens the slurry-wall solution to placing upside down bucket over the contamination site — nothing can infiltrate the cap from above, and nothing can move laterally through the sides, which are bentonite clay; rather, the weakness is where the bucket joins a geologic formation beneath the surface of the earth, to what’s called an aquitard.

“Water is our enemy in this situation. And basically, we’re putting a bucket over the site so that no water can get in or out. The bottom of the bucket is still open. And we said that the failure point for the slurry walls depends on how well you can tie into an aquitard,” Peacock said, noting that most of the subsurface material beneath the CFAC site is unconsolidated glacial till from the last ice age, which isn’t particularly reassuring on the permeability scale.

“These are questions I don’t see answered anywhere in the plan, and from what I am hearing from you so far is that’s the part that still is requiring lots of investigation,” Peacock said. “But we’re talking about an unknown, whereas we do know what all of the knowns are for just removing and disposing. And I keep hearing that cost is not an issue, and yet, cost is mentioned over and over and over in the proposed cleanup plan. But Glencore is a company whose global profit is in the order of twenty-some-billion dollars a year and here we’re worried about something that’s maybe $624 million over a six-year period. My math tells me that’s about 50 cents to every $2, so cost should not be an issue especially when we’re talking about community health and something that has to last us hundreds of years. But my question is I need to understand the bottom of this open-ended bucket better to feel very comfortable that we have eliminated the ability of water to get in and out of this. The top is good, the sides are good, the bottom is the failure point; that is our unknown and I don’t think we have the information we need to move forward.”

Deming said Peacock’s bottom-of-the-bucket analogy is spot on, but added that engineers will perform testing on the glacial till to understand its permeability, and they’ll refine their modeling of the groundwater plume’s movement, as well as its changing chemistry and response to the fluctuating water table. Moreover, the containment cell would be designed and constructed in a manner that maintains an inward flow of groundwater, and that contaminated groundwater would not have an opportunity to migrate out of the cell.

“While it may sound that we don’t know yet, we know it’s a sure thing. An absolutely sure thing,” Deming said. “You’ll keep the bottom of the bucket tight if you keep the water level low enough inside the site, because then instead of the water going out all of the outside water wants to come in. You just sip the straw enough to keep that going. That’s the bottom of the bucket. But we’re going to test it, we’re going to understand it, we’re going to have models that help us understand how it works, and I think your concerns can be addressed.”

Dorrington acknowledged that extensive work lies ahead before the design of the plan can be executed; but, he said, “that is the purpose of the design, to reduce or eliminate those uncertainties as you go towards a final implementation. But enough work has been done to say this is the best cleanup alternative.”

“The next step is to determine and identify and solve those unknowns,” Dorrington said.

Peter Metcalf, a Columbia Falls resident who helped form the grassroots organization Coalition for a Clean CFAC (CCC), whose members and supporters passed out literature and stickers on Wednesday night, said that another unknown lurks for him and his growing coalition of community members — that of corporate responsibility and the extent to which Atlantic Richfield Co. (ARCO), a subsidiary of BP America, and CFAC, a division of Glencore, are held accountable.

Since 2016, the question of who should bear responsibility for CFAC’s past and future cleanup costs associated with decades of contamination at the property has fallen under the purview of the federal Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA). CERCLA, as well as its state analog, the Montana Comprehensive Environmental Cleanup and Responsibility Act (CECRA), allow the corporate owners of a contaminated property to offset their liability by seeking recovery costs from previous owners. In this case, CFAC, which Glencore purchased in 1999 and closed in 2009, nearly 15 years after ARCO sold the plant to the Montana Aluminum Investors Corporation, has sought to assign some of the cleanup costs to ARCO.

The question that Metcalf had is, once the cleanup is complete, the site delisted and the property repurposed by a new owner, who assumes the onus of financial responsibility in 40 years if, for example, the slurry wall fails?

“Glencore will be liable for the cleanup of this site,” Dorrington said. “In terms of long-term liability and responsibility for this site, Glencore will always be responsible for that footprint and what happens in there. The condition of the cap, the performance of the slurry wall — they are responsible financially.”

Along with other members of CCC, Metcalf thanked EPA and DEQ for making the time to conduct another round of community-engagement sessions, saying he hoped it signaled the first of many steps to come in the evolving outreach campaign. Earlier in the week, the EPA provided CCC with Technical Assistance Service for Communities (TASC) support as a stopgap measure until the group’s application for a Technical Assistance Grant is awarded. The financial assistance will allow CCC to hire independent technical advisers to help inform its members throughout the engagement process and conduct their own evaluations.

The TASC assistance can be used “while the Technical Assistance Grant application for CCC to organize and support public engagement efforts is being processed and eventually awarded,” according to a letter by EPA’s Carolina Balliew. “The TASC will allow CCC to select a technical advisor in the coming weeks who will work alongside you throughout this extended engagement process.”

Even as the EPA prepares to document its selected remedy for the CFAC cleanup in a Record of Decision (ROD), Dorrington explained Wednesday that it could be a year before the plan is formalized and three years before the cleanup work begins.

Until then, nothing is off the table.

“Until the ink is dry on that ROD, anything could change. That’s the beauty of this process. It can be modified.”