A Matter of Life and Death

Four men have died at the hands of Flathead County law enforcement in the last 12 months, an unprecedented spree that’s left a trail of heartache and unanswered questions

By Andy Viano

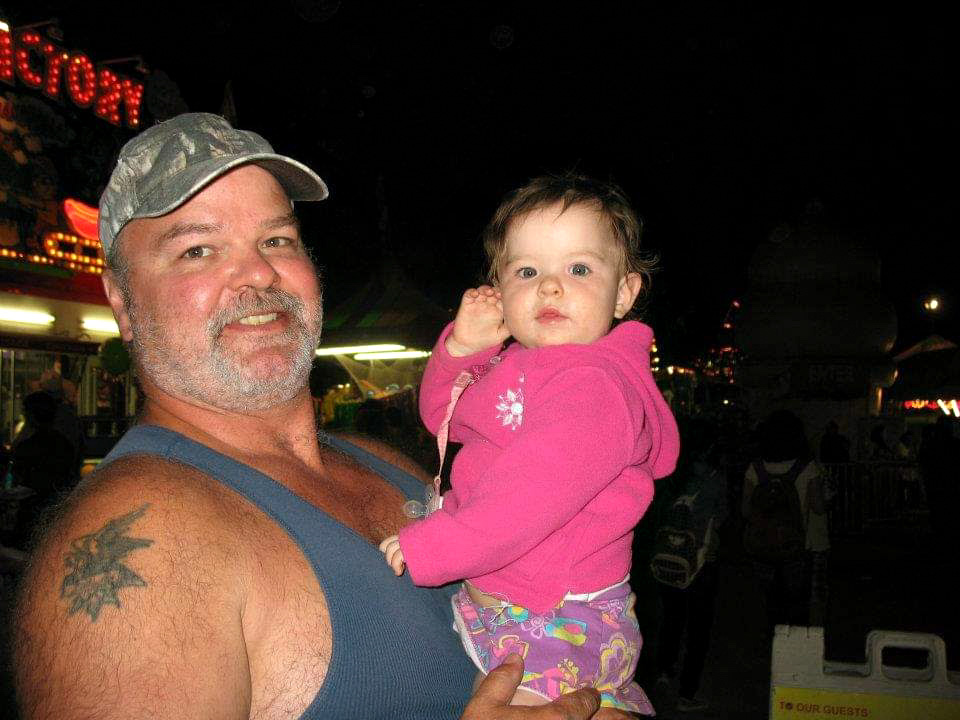

On Valentine’s Day in 1989, just two months after he was set up with her on a blind date, Anthony Dale Grove bought his girlfriend Dawn two-dozen long-stem roses and an engagement ring. Six months later, they were married, and for the next 30 years the Groves always had each other.

As 20-somethings in Arizona, Dawn enlisted in the U.S. Army, serving during the first Gulf War, and Anthony, who she calls Tony, collected paychecks as a bouncer, including at a topless bar. Tony was a bear of a man, standing six feet tall but with arms as big as his thighs, and was an outstanding athlete as a teenager, Dawn said, starring on the football field in his hometown of Baker City, Oregon. As he grew older, his wife teased that Tony got “rounder in the belly,” packing on the sympathy pounds every time she got pregnant.

The Groves have three children, Jessica, Jennifer and Jozi, and raised them all in the quintessential Montana way — hunting, fishing, adventuring and telling stories around the fire. And as burly as Tony was, Dawn says her husband was more teddy bear than grizzly, a man who “never met a stranger,” who showered his girls with “the hugs, the kisses, the smiles (and) the jokes” and was there to lend a hand to any neighbor in need. In 2013, the Groves moved into a secluded property on Rogers Lake Road in Kila, where they could feel even more connected to the outdoors. Their land is several miles from U.S. Highway 2 and their house sits at the end of a long driveway, much of it surrounded by thick woods.

Like anyone, Dawn and Tony’s 30 years of marriage were not without ups and downs, but the good days outweighed the bad ones. For the most part, their lives consisted of their daughters, their neighbors, their movies and popcorn, their drives through the woods, and their quiet evenings spent cooking stir fry side-by-side in their kitchen.

But May 24, 2020 was a bad day.

Tony and a friend spent that morning butchering pigs and drinking beer, the latter of which was a no-no for the 52-year-old Tony who had just been diagnosed with the beginning stages of a serious lung disease. The medication he was taking didn’t mix well with alcohol, and when Dawn got home that evening and saw that her husband had been drinking, they argued. Viciously. Dawn put her wedding ring on the counter and Tony told her to get out of the house. He was armed. Their eldest daughter and a granddaughter were in the house as well, and as the confrontation escalated, Dawn told her daughter to call 911. Tony shoved his daughter, followed the women out of the house, and fired a gun in the air as they drove away in separate vehicles.

Almost a year later, Dawn, her two grown daughters, a handful of law enforcement officers, and a jury of their peers all sat in the same courtroom in downtown Kalispell and listened to that frantic 911 call. They heard about the argument, about the gunshot, and about how Dawn and Jessica drove to safety. They saw a despondent Tony declare he was “going to be killed tonight” in a Facebook video recorded as he sat, alone, inside his home. They watched drone footage of Tony, always armed, pacing up and down the long driveway, and they saw him shoot at the drone doing the filming. They heard a combative call from a Flathead County Sheriff’s Office (FCSO) negotiator and heard Tony tell that negotiator he had “more ammunition than you’ve got blood cells.”

And then they watched Tony Grove step out the front door of his house, fire his gun in the direction of a SWAT team stationed nearby, and die in a hail of gunfire.

“I’m broken, I’m just so broken,” Dawn said in the days following her husband’s death. “He was my partner and now I don’t have it anymore.”

On the day Tony Grove was killed, it had been more than 13 years since the FCSO had been part of a shooting that left a suspect dead. Before the end of February, just nine months later, it would happen three more times.

In June, 59-year-old Richard Mason was shot and killed after a vehicle pursuit ended in gunfire near Woods Bay, just hours after Mason was suspected of murdering a 62-year-old woman.

In December, local officers were involved in a standoff that ended with an unidentified 35-year-old man dead outside the Naughty Pine Saloon in Trout Creek. A Kalispell Police Department (KPD) officer was injured in an exchange of gunfire that day, the first time in the department’s more than 100-year history that an officer was shot on the job. She was not seriously injured.

And in February 2021, 41-year-old Isaiah Strong was shot to death inside a gas station convenience store in Kalispell after allegedly attacking a KPD officer and another customer with a large wooden object. A bystander was also shot and injured.

Coroner’s inquests, like what was held in the Grove case on May 7, will be held in the three other deadly encounters in the coming weeks, but thus far no internal or criminal investigations have revealed any wrongdoing by law enforcement (KPD’s internal review of the February shooting is ongoing).

Whether the inquests will ultimately prove the shootings justified or not, they represent just a fraction of the officer-involved deaths statewide. Since the start of 2020, 33 in-custody deaths had been reported in Montana, a relatively small number given the tens of thousands of calls for service officers respond to, but a concerning trend that continues in 2021. According to data provided by the Montana Department of Justice, there were 31 total in-custody deaths — which could include suicides in the presence of law enforcement along with deaths caused by officers — in the state between 2012 and 2017. In 2020 alone there were 21 such deaths, and through May 9 there were already 12 more in 2021.

“Alarming is the best way I can describe it, and disturbing,” Bryan Lockerby, the head of the state’s Division of Criminal Investigations (DCI) and a 40-year-law enforcement veteran, said. “To see these trends is a great concern.”

Lockerby says he has several theories on why in-custody deaths are on the rise, including an increased reliance on law enforcement to respond to mental health emergencies, and said drugs and alcohol also regularly play a significant role. Since 2020, of the 13 victims of police shootings who were examined and given a toxicology screening, 12 were under the influence at the time of their death.

KPD has been involved in three of the four fatal shootings — they were not part of the incident near Woods Bay — and Chief of Police Doug Overman has his own theory for what’s caused the spike in deadly confrontations.

“People’s mental health is struggling,” he said. “I don’t know if that was a result of all the stress everyone had in the last year, I don’t know if it manifested itself in that way, but the timing is conspicuous.”

Whether there is a single cause or causes to blame for the increase, law enforcement officials are unanimous that a loss of life is the worst possible outcome in any interaction, and not just for the families of the victims.

At least seven officers, deputies and troopers from the FCSO, KPD and Montana Highway Patrol have been involved in fatal shootings in the last year and, per department protocols, all were immediately placed on paid administrative leave. The shootings also trigger simultaneous investigations: a criminal investigation conducted by an outside agency, often the DCI, and an internal review by the department involved. After the criminal investigation is complete, a coroner’s inquest is held, in which the evidence is presented for a jury and that group decides whether or not the death was caused by criminal actions.

The inquest covering Grove’s shooting came nearly a year after his death, meaning not only has Grove’s family waited for answers but the three officers who fired a total of 30 rounds at him — KPD Lt. Jordan Venezio, FCSO Sgt. Logan Shawback and FCSO Sgt. Travis Smith — have been waiting to find out whether or not they would be criminally charged. All three had previously been cleared of wrongdoing internally and returned to work, but because they were the subjects of active investigations (in this case by the Missoula County Sheriff’s Office) they could not discuss the case with their colleagues. Instead, they are given access to mental health resources, including therapists who specialize in treating post-traumatic stress disorder.

“I have seen the pain in people’s lives, in their eyes,” Overman said. “It’s all a tragedy. It’s a tragedy for (Grove). It’s a tragedy for his family. It’s a tragedy for my officers involved. It’s difficult for a community.”

Flathead County Sheriff Brian Heino, who, like Overman, had never experienced a deadly shooting before last May, said reverberations from such an incident are felt broadly throughout the department and acutely by the deputies who make the split-second decisions to pull the trigger and take a life.

“There’s this quietness, this numbness,” Heino said of the deputies involved. “The tough part is everybody’s a human being and some people deal with it this way, some people deal with it different ways. But I would say it’s still on the forefront of their minds; it’s not like it just went away.”

“From an administrative standpoint, the odds are not in your favor,” Heino added. “The majority of people involved in deadly shootings, or who get shot, they make it four or five years and then they’re gone … You sign up for the job to help people and then you get put into circumstances where you have to make a tough decision in a two-second window; rapid decisions that you’re making and then you’re judged on for one full year. It takes its toll on people.”

Smith, Venezio and Shawback will not face criminal charges for killing Tony Grove. A nine-member jury took less than 30 minutes to decide that the shooting did not constitute criminal conduct following a full day of hard-to-watch evidence and hard-to-hear testimony.

The inquest, overseen by Powell County Coroner Heather Gregory and directed by Flathead County Attorney Travis Ahner, ended with Grove’s family audibly frustrated, even as the decision appeared inevitable. Following the verdict, Grove’s daughter, in earshot of law enforcement and the jury, said the cops who killed her dad had gotten away with “murder.”

Dawn Grove was frustrated at the end of the day, too, but acknowledged the outcome was likely even before the verdict was read. For Dawn and her family, fewer questions linger about the final seconds of Tony’s life — the drone video clearly shows sparks flying from his lever-action rifle in the direction of officers before they return fire — but burning questions persist about the hours leading up to it.

From the first 911 call to the final gunshots, the entire incident unfolds in less than three hours. In recorded interactions played at the coroner’s inquest and obtained through open records requests, Tony Grove is clearly intoxicated and repeatedly warns officers to stay away from his house, agreeing to talk to officers only if they’ll meet him at his front door. FCSO Deputy Charles Pesola, who had three phone calls with Grove in his role as a negotiator, described Grove as argumentative and combative throughout their interactions.

Jessica Grove was interviewed by two FCSO deputies and gave a written statement shortly after calling 911, and she repeatedly told officers her father was armed and expressed concern that he may react violently. In testimony on May 7, she said she was concerned that her father was suicidal and while the words aren’t spoken, it’s clear officers were aware that Tony could have been contemplating “suicide by cop.”

Sgt. Sam Cox was the first officer on the scene and conducted the first interview with Jessica. Upon assessing the situation, he staged at the bottom of the Groves’ long driveway and began to set up a perimeter. He also requested tactical assistance, which later came in the form of a SWAT team consisting of two armored vehicles and law enforcement from FCSO and KPD. Cox also asked a fellow deputy who operated a law enforcement drone to start taking video of the area for officers to formulate a plan.

At no point, every law enforcement officer who was asked agreed, did Grove ever appear to be de-escalating the situation. There is no audio with the drone footage, but in the 20 or so minutes shown during the inquest, Grove is clearly agitated, waving his arms, gesturing aggressively and picking up various firearms.

When the SWAT teams arrive on the scene, the decision is made to send the two armored vehicles up the driveway and park them feet from Grove’s porch, next to a garage. An arrest team — Venezio, Smith and Shawback — exit their armored vehicles and take cover nearby. Pesola continues to attempt to negotiate with Grove through a loudspeaker but those negotiations go nowhere. If anything, Grove only escalates his behavior once the SWAT vehicles arrive, at one point emerging from the house with a gun in each hand and twirling them in his hands, briefly aiming them at the officers. It’s a short while later that Grove once again escalates his behavior, fires his gun, and is killed.

The tactical decisions made on May 24 were not included in the narrow scope of the coroner’s inquest but Dawn Grove remains baffled why law enforcement continued to engage with her husband, even though he was clearly in a highly agitated state and at home alone, where he did not pose an imminent threat to anyone other than himself.

“You’ve seen … all the different instances where somebody has been irrational and they’ve walked out of it alive because they have backed off, stayed their distance, monitored it but didn’t engage,” she said. “All that happened for two hours was constant antagonizing. Did it escalate? Yes. Was (Tony) as much at fault as they are? Yes. I’m not saying he was in the right, that is not it, but something better should have happened.”

Heino and deputies involved with the incident said the situation is not as simple as giving Grove time and space to cool down. The final confrontation occurred after 9 p.m., with the sun setting a short while later, and the team would have lost use of the drone in the dark. Without that footage Grove could have left the property without them noticing and still could have presented a threat to Dawn, Jessica or others. Heino also noted that Grove had already fired weapons several times during the incident — once in front of Dawn, several times at the drone, and other times when officers heard but did not see shots fired.

At the end of the day, criminal charges will not be filed in Grove’s death but Dawn remains hopeful that other legal avenues could produce change, including a possible civil suit. And for their part, Overman and Heino said they are constantly evolving their practices to try and avoid these types of situations, and learn how to respond to every situation as safely as possible — for the suspects, their officers and the community.

“I want them to do better,” Dawn said. “The training needs to get better, it has to get better, or more of our husbands are going to die.”