To Defund or Defend?

Amid congressional efforts to defund Glacier National Park’s vehicle reservation system, park administrators and stakeholders defend it as an adaptive tool that has evolved based on public feedback

By Tristan Scott

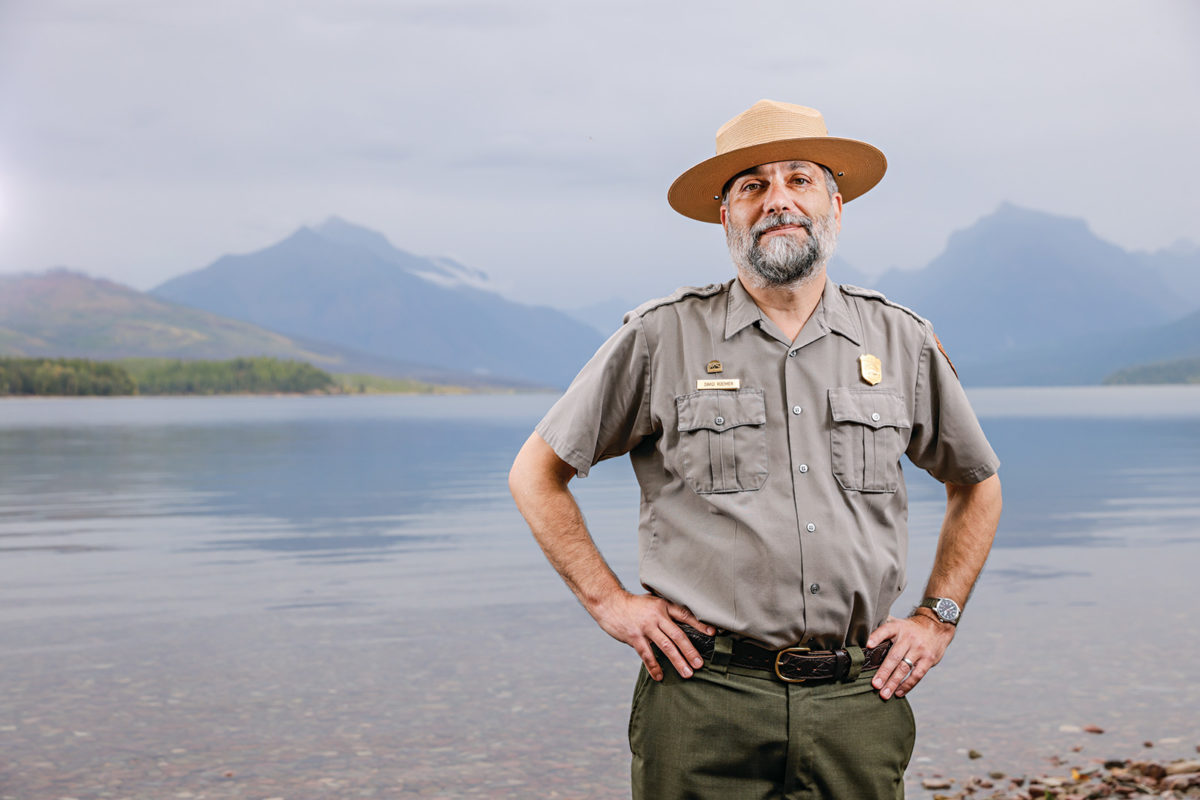

For Dave Roemer to travel back in time, he has only to step out of his office at 3 p.m. and walk a block to West Glacier.

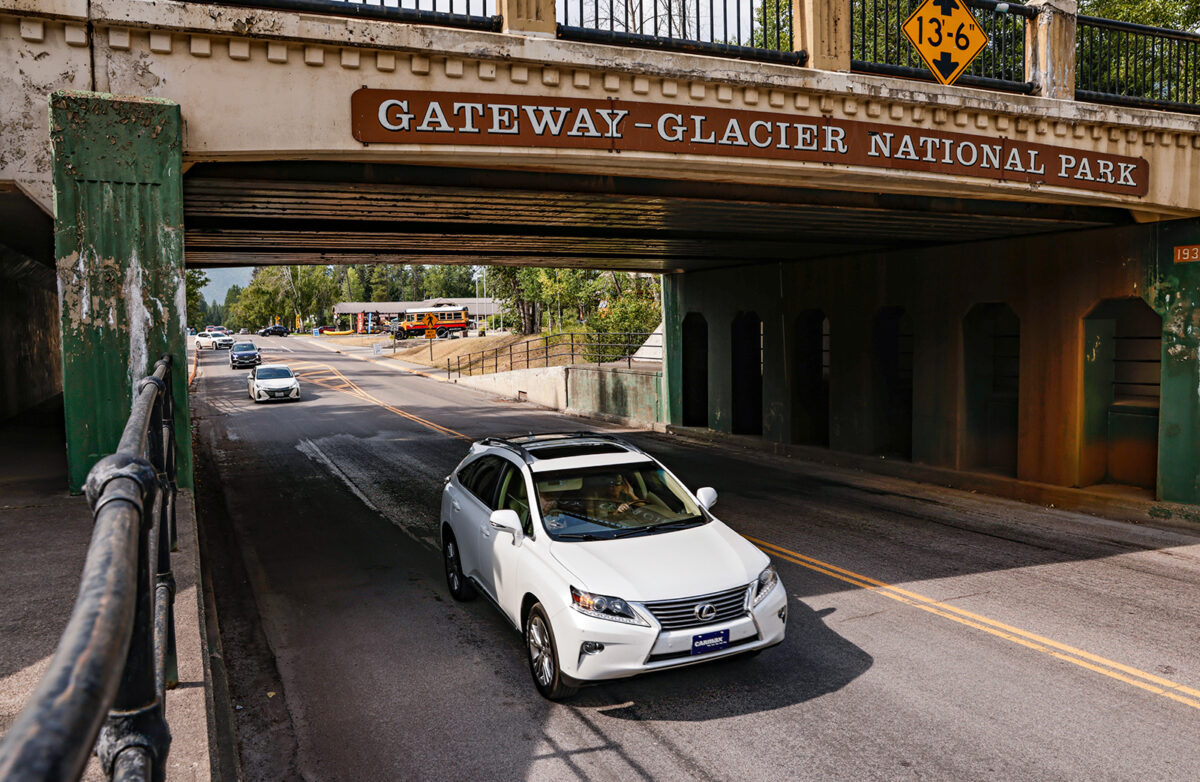

From that vantage, he can glimpse the gridlock that subsumed Glacier National Park’s management team prior to his appointment as superintendent. He can watch in real time as the pent-up crowds converge in anticipation of the park’s vehicle reservation requirement lifting for the day, and he can imagine those same conditions sustained for hours at a time, just as they were in the recent past, forcing closures at the park’s most popular entrances on most days during the busy summer season.

But then, almost as soon as the traffic begins to snarl, the knot of congestion breaks apart into an orderly queue along the iconic Going-to-the-Sun Road.

The same experiment can be tested in the park’s remote North Fork region, where motorists crowd the entrance at Polebridge waiting to drive the wash-boarded gravel road to Bowman or Kintla lakes, but not until the clock strikes 3 p.m., signaling the closure of a daily reservation window that has opened at 6 a.m. every day since the end of May.

The same brief bouts of intense congestion have also occurred at two of the park’s most popular arterials east of the Continental Divide, Many Glacier and Two Medicine, although the reservation requirement didn’t start at those entrances until July, as visitation pressure intensifies later on the east side.

Over the past two decades, annual visitation at Glacier National Park has increased from approximately 1.5 million to over 3 million visitors, most of them concentrated along the Going-to-the-Sun Road corridor and other front-country destinations during the peak season of June through September, creating severe congestion at the park’s most popular entrances.

“There is an infinite number of opinions about how the National Park Service should manage visitation in this new era, but there is a very finite amount of parking lots and miles of paved roads and other facilities to host people in Glacier Park,” Roemer said. “Our popularity has grown beyond what our infrastructure can support, and we need to be able to have tools to spread things out so people can continue to enjoy the parks for what the parks are without impairing our resources.”

When the park first introduced its managed access system in 2021, it was only in place at the West Glacier and St. Mary entrances, where the reservation period started at 6 a.m. and extended until 5 p.m. That created a pinched-balloon effect, whereby park visitors caught unaware by the new vehicle-reservation policy would migrate en masse to one of several unrestricted entrances, some of them hours away. Even so, by mid-morning the entrances would be overwhelmed and forced to close for the day.

Park officials learned from those shortcomings and adjusted the system to include the North Fork in 2022, while also narrowing the hours during which reservations were required, from 6 a.m. – 4 p.m. That allowed visitors without a reservation to take a sunset drive along the Sun Road or enjoy an evening hike. This year, the reservation requirements were expanded to include Many Glacier and Two Medicine, but the hours were pared back to 3 p.m., easing any sign of gridlock on most days except during that brief period just after the requirement is lifted.

That’s when Roemer takes a stroll down to West Glacier or checks in with his operations team at another entrance, both to remind himself how bad things could be and to appreciate how far the park has come.

“With the reduced hours of this year’s managed access system, in some ways we have an opportunity to experience the conditions of both extremes in a single 24-hour period,” Roemer said. “We’ll get that brief build-up right at the top of the hour, and then it’s over. We think we may be dialing in the sweet spot right now.”

To dial in that sweet spot even further, Glacier National Park administrators will host a trio of upcoming civic-engagement sessions to gather public input and help inform a strategy for summer 2024.

Those sessions will unfold through the end of August as the park closes out its third summer piloting a vehicle reservation system for major park entrances. The pilot project was initiated in summer 2021 at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, as a response to increasing issues with traffic congestion that included backups onto U.S. Highway 2, strains to infrastructure capacity, and impacts to park resources from high concentrations of people in its most popular areas. Ongoing pilot reservation systems in summers 2022 and 2023 have provided opportunities to learn more and explore their viability in achieving desired conditions in the park, Roemer said.

“In my job I have a tendency to focus on the negative, on the complaints, but I should share that we also have people from the local area who write to say that we are doing a good job with this,” Roemer said. “We hear from people who say they are enjoying their visits to the park whereas they didn’t before because it had become too Disney-ified, too crowded. Now they have a higher degree of certainty that their experience will be rewarding.”

That learning curve, while steep, is beginning to resonate with a growing number of visitors who report a higher quality experience once inside the park, as well as with gateway business owners and tourism leaders who say people are coming to Glacier better prepared to navigate its reservation requirements, which hasn’t always been the case.

“There have been some warts,” said Darin Fisher, who along with his wife, Carla, owns Backslope Brewing in Columbia Falls, a growing gateway community situated 10 miles from Glacier’s west entrance. “Carla and I are both big fans of the reservation system, even if it has been far from perfect. Some of the changes from year to year have not been rolled out as well as they could have been, but with that said, we have been able to get reservations to the park, our staff have been able to get reservations to the park and when we talk to the visitors who come through the brewery, the ones that have their reservation and have prepared for their visit report having the best experience.”

Laura Hodge, project coordinator for the Crown of the Continent Geotourism Council, said the park’s messaging surrounding the rollout of the reservation system has been awkward in part because the policy isn’t uniform. That’s important in a park whose 1 million-acre footprint is geographically and socially diverse, but it runs counter to the principles of Marketing 101, Hodge said.

“One entrance is not the same as another, so in that respect it makes sense to have different rules for different entrances. But it really is an overwhelming amount of information, and that makes it harder for the public to understand,” Hodge said. “They should be communicating at a fifth-grade learning level, but at the start of the season it’s like reading a manual. But they have tried to simplify it and make it easier for people to understand. I think the worm is starting to turn and people are starting to warm to what was very complicated and felt very punitive in the beginning.”

But Hodge also hears from visitors who report a positive experience along the Going-to-the-Sun Road corridor, including at popular parking lots such as Logan Pass.

“We just drove back from the east side on the Sun Road, and there were lots of spots at Logan Pass,” Hodge said. “Instead of people getting into fist fights over a parking spot, there were bighorn sheep hanging out. It was exactly the experience that you should be having in a national park on a Saturday night in the summer. And I attribute a lot of that to the reservation system.”

The correlation that Fisher and Hodge draw between improvements to the reservation system and an enhanced visitor experience is born out in data, too.

During the summer of 2021, a social science team from Utah State University collected visitor intercept surveys in Glacier about their experiences with what was then called the “pilot ticketed-entry system.” Over 500 visitors were intercepted at four locations in and adjacent to the park: West Glacier townsite, Avalanche Lake trailhead, the Polebridge Mercantile, and at the Two Medicine beach area.

Some of the key findings include: 91% of respondents were not residents of the local area; 69% were first-time visitors; 56% of respondents were able to get tickets for their desired days; 70% of respondents would prefer to have a reservation system of some kind in place on future trips along the Going-to-the-Sun Road corridor.

Meanwhile, new visitor-use data also reveal that the experience is improving at other popular national parks that have implemented reservation policies. A study by Utah State University (USU) reflects positive results from 2022, the first year of timed entry access to Arches National Park. An 89% majority of survey respondents successfully acquired a timed entry ticket for their visit. Of that number, 98% were able to enter on their selected day.

Based out of Salt Lake City, Utah, Cassidy Jones works for the National Parks Conservation Association (NPCA) to better understand how visitors are responding to managed access systems. Jones said gateway communities that are dependent on their national parks for economic sustainability, such as Moab, Utah, have also warmed to the systems as they’re refined.

Similar to Glacier’s system, most timed entry tickets for Arches are released three months in advance, while the park also opens a select number of tickets for purchase one day in advance.

But Jones said a better corollary for Glacier lies in Rocky Mountain National Park, which has adopted a timed entry system as well as two separate types of vehicle reservations — one for its popular Bear Lake Corridor, and another for general park entry.

“It’s going really well at Rocky, but you have these two different kinds of reservations, and it’s more complicated for visitors to understand the distinctions. Glacier is probably even more challenged to communicate its distinctions because it is so unique,” Jones said. “But Glacier has been through this great adaptive journey, making changes based on visitor behavior and visitor movement.”

Still, not everyone wants to see Glacier’s managed access system continue in its fourth iteration. The reservation requirement has rankled locals who miss a bygone era when an impromptu park visit wasn’t such a logistical ordeal, and U.S. Rep. Ryan Zinke, the Republican from Whitefish who served as Interior Secretary during the Trump administration, has been hammering on the system since this spring. Zinke, who oversaw the National Park Service (NPS) before resigning amid a cloud of ethics investigations, recently introduced legislation to defund and block the vehicle reservation system. In July, the House Appropriations Committee approved the proposal, adding an amendment to the FY24 Interior, Environment and Related Agencies funding bill, which will advance to a vote on the House floor in September.

According to Zinke’s chief of staff, Heather Swift, “some at the NPS are singularly focusing on one aspect of Congressman Zinke’s position which is to do away with the vehicle reservation system, while ignoring everything else he is doing legislatively that addresses exactly these concerns.”

For example, Swift said Zinke has repeatedly called for an expanded shuttle system, and recently introduced the bipartisan Gateway Communities and Recreation Enhancement Act that requires the NPS to consult local communities before restricting access to parks — “Park leadership must have thought Zinke had a good idea because Glacier just announced they are hosting the first public meeting on the reservation system,” Swift said.

“Federal land managers have been pushing down bad policies without getting input from locals. Now the locals have had enough and are pushing back,” she added. “Everyone the congressman talks to in the Flathead, from the airport director, to a small inn keeper, or county commissioner, they all have stories about the negative impacts of the reservation system on their businesses and the area economy, and of course there’s also the personal hit on folks not being able to enjoy the park.”

Glacier Park has hosted stakeholder engagement meetings since it first introduced the concept of a managed access system in late 2020, and some business owners believe their feedback made a difference.

Sanford Stone, whose family owns Park Cabin Co., a hospitality and lodging business in Babb, situated on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation that abuts Glacier’s eastern boundary, has been a vocal critic of the park’s reservation system and hasn’t been shy about sharing his input during the stakeholder meetings with park officials that have bookended the past three years.

Although Stone says the system remains imperfect, to his surprise the park appears to be listening to public feedback.

“As a business owner, I was glad that the park service involved us in their stakeholder meetings the past few years and certainly seemed to incorporate our feedback. Less restrictions over here continue to make sense as we simply don’t have enough occupied rooms to overload the entrances in the fashion that the Flathead can do in a moment,” Stone said. “I guess I’m not very interested in defunding anything about the Park Service when there is still so much deferred maintenance and room for improvement, especially here on the east side.

The proposal to defund the reservation system has played well with some stakeholders, but others say the consequences could be catastrophic, pointing to Yosemite National Park as an example of what can happen when attendance restrictions are suddenly lifted. Yosemite, like Glacier, had piloted a vehicle reservation system to mitigate congestion in recent years. This year, however, Yosemite decided to pause the pilot while it began a public engagement process to consider long-term solutions that balance visitation and access with public safety and the protection of park resources.

With the attendance restrictions lifted, however, Yosemite’s overcrowding crisis reached new heights as lines kept motorists waiting for up to three hours and human waste deposits were reported in parking lots and at trailheads — issues that are familiar to Glacier Park officials.

Rather than face that extreme for an entire summer, Roemer said he’s looking forward to hearing from visitors at the upcoming civic-engagement sessions and adjusting the park’s policies based on feedback.

“We appreciate Representative Zinke’s input and comments, but we are not planning right now for what we might do in the case of his pending legislation,” Roemer said. “We really want to make those decisions through a more full and robust public process, based on hearing more broadly from user groups. Some of the conditions of overcrowding, if they are not managed or if they are managed from a reactive stance, are a detriment to park resources and to the visitor experience. Conditions of gridlock is no one’s idea of a good time in the park, and it’s not safe.”

Gina Icenoggle, Glacier’s communications officer, acknowledged that education and outreach to visitors and business stakeholders hasn’t always been fluent.

“Part of the pilot system is that we are piloting different strategies and gathering feedback each year that we have had the reservation policy in place,” Icenoggle said. “That does make it a bit confusing because nothing is consistent from year to year, and unfortunately that is just kind of part and parcel of having a pilot program. But it’s a result of us being responsive to the public’s feedback.”

In addition to trying new marketing techniques, Icenoggle said the nonprofit Glacier National Park Conservancy funded a visitor use management and public affairs specialist to help with improving communications surrounding the pilot system, as well as to gather and analyze comments published to the park’s social media channels. The Conservancy also funded a vehicle reservation call center to handle the volume of inquiries from the public.

“We have taken that feedback and revamped the Glacier National Park website and have tried to make other improvements,” Icenoggle said.

Among the most infuriating experiences that visitors report having is the use of a third-party online reservation portal, recreation.gov, which is the National Park Service’s official booking website. Although a portion of reservations were made available months in advance using a block-release system, the remaining vehicle reservations are released on a rolling basis every summer morning at 8 a.m. Those can be made 24 hours in advance of a planned trip, but there are only a limited number of vehicle reservations available for each day, with demand exceeding supply.

Visitors describe the online portal as an anxiety-inducing lottery, although those who log in at 8 a.m. promptly rarely report walking away from their computer empty handed.

“Even if you log on right at 8 a.m., there’s a tension as you watch the reservations disappear,” Hodge said. “I don’t know what the answer is, but I do feel that is still a sticking point. Maybe it would behoove the park to stagger the releases in batches at 8, 10 and 12. And I think people forget just how complicated it is for people visiting from other places.”

“But remember, Glacier National Park was never intended to hold 3 million people a year. The infrastructure isn’t there,” Hodge added.

Roemer and his staff have heard the complaints surrounding the recreation.gov system, which for now is the best the federal agency can do, he said.

“We’re aware of some of the displeasure with how the system works,” Roemer said. “I also know that if we didn’t have that, and if Glacier National Park had to invent its own operating system to manage the reservations right now, it would not be nearly as elegant.”

With so much focus on the park’s reservation system, Stone said it’s easy to lose sight on the numerous issues that have plagued NPS units for years, such as the deferred maintenance and staffing shortages that have beset Glacier for years.

“If people want to ‘defund’ the vehicle reservation system or otherwise get rid of it, that’s fine with me if there is a plan to keep the park from being overrun and a miserable driving and hiking experience,” Stone said. “How do we fund a better transit system? Will that require a lot more infrastructure, especially in the St. Mary area? What does it mean for driving a personal vehicle over the Sun Road?”

“As a person that likes to actually enjoy the park, I think ticketed entry is a huge success — parking, hiking, the overall experience is just so much more pleasant than it has been dating back to the couple of seasons pre-covid,” Stone added. “I hope they’ll continue to make corrections, but even with that, it is a huge pain to re-educate our prospective guests when the park can’t finalize a plan until the spring and everything changes every year. I don’t think the system itself is the issue, just how it keeps changing, the park’s messaging about it, and the perception that it will render a vacation somehow less than it should be when in fact we haven’t had a single guest unable to enjoy the park.”

For Hodge, the system remains a work in progress, and the pitfalls are worth the protective values that the reservation system has furnished on Glacier National Park.

“Ultimately, the common ground is that we all love the park,” Hodge said. “And we all want to have access to it, but we can’t love it to death. And to me, the reservation system is to protect what we love and to be good stewards of it, both now and for future generations.”