Tribal, Federal Water Managers Host Informational Meeting on Flathead Basin Operations

After last summer's record low lake levels, agency officials and dam operators held a presentation on the history and legal operations of Hungry Horse and SKQ dams

By Micah Drew

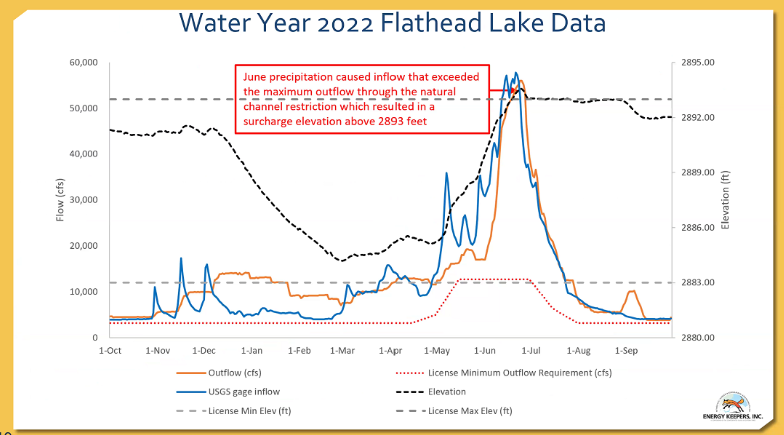

In May of 2022, snowpack in the regions of northwest Montana that drain into the Flathead River basin were at 226% of the 30-year average. The high amount of snow-water equivalent, combined with record rainfall in early June sent torrents of water rushing into the river, which rose past flood stage in Columbia Falls, Kalispell, and Creston. Downstream, inflows to the lake exceeded the maximum outflow capacity of Seli’š Ksanka Qlispe’ (SKQ) Dam causing Flathead Lake to overfill by several feet.

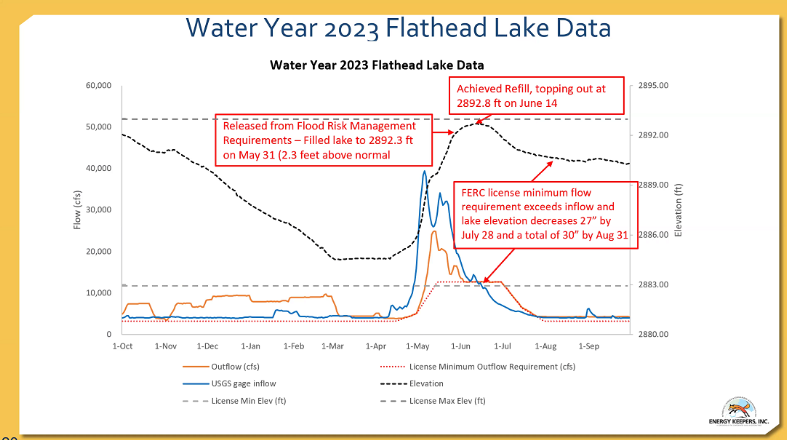

Last year, a low snowpack followed by record warm spring temperatures led to a rapid melt out in May and by mid-June the water level of Flathead Lake began dropping precipitously. Despite dam operators doing everything within their legal operating license to stem the lake’s decline, water levels ultimately reached more than two feet below full-pool capacity, jeopardizing some business interests and recreation opportunities.

“There’s a very big difference between the two years,” Leeann Allegreto, a meteorologist and hydrologist at the National Weather Service office in Missoula, said on a call Thursday afternoon. “The point I want to drive home here is that last year, the snow just kept melting and melting and melting and runoff got lower and lower and lower. [By June], we just ran out of runoff.”

Allegreto was one of several agency officials who joined Brian Lipscomb, CEO of Energy Keepers Inc., the owner and operator of the SKQ Dam, for a presentation describing the challenges of managing the hydropower network spanning the Pacific Northwest. The meeting was intended to inform residents of the history of both SKQ and Hungry Horse Dam, which generates power along the South Fork Flathead River, how the two projects fit into the wider federal Columbia River management plan, and how environmental factors throughout the year directly impact the water levels seen in Flathead Lake during the summer.

Others on the call included officials from the Bureau of Reclamation, which operates Hungry Horse Dam, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which operates 10 federal dams in the northwest, including the Libby Dam, and directs flood control operations.

As of March 1, water supply forecasts for the Flathead Basin were at 72% of normal. “It’s not ideal, but we still have plenty of time, at least through April, to try to get those numbers up with additional snow or rain on snow as we get into May,” Allegreto said. “And not all hope is lost.”

The informational presentation began with a history of the two dams that bookend the Flathead Valley.

Congress authorized the construction of Hungry Horse Dam in 1944, and the 560-foot-tall concrete dam was completed in 1953. At the time, it was the fourth largest concrete dam in the U.S., requiring the equivalent of 77,000 garbage trucks full of building material.

The reservoir formed by damming the South Fork Flathead River contains approximately 3.5 million acre feet of water and can generate up to 408 megawatts of power from its four power plants.

The Bureau of Reclamation manages the dam for multiple purposes, including flood risk management, hydropower generation, recreation, and fish and wildlife conservation under the Endangered Species Act.

Four and a half miles downstream from the outlet of Flathead Lake, SKQ Dam began producing power in 1939. The federal power commission issued a 50-year operating license to the Rocky Mountain Power Company, which later transferred the license to the Montana Power Company. The Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes (CSKT) filed a competing bid for the license when it came up for renewal and after co-operating the dam for decades acquired the dam’s license outright in 2015.

Under the current federal license, the dam controls the top 10 feet of water in the lake. The license allows the lake to be filled to full pool around June 15 of each year but does require full-pool elevation for the duration of the summer.

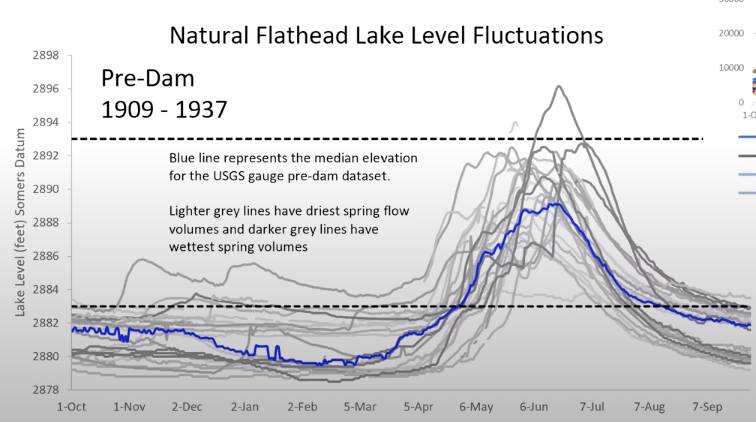

“Before the construction of SKQ Dam, the lake level naturally fluctuated throughout the year due to the channel restricted outflows,” said Eve James, director of asset optimization with Energy Keepers. “Before the dam, there was a large range of summer lake levels … lake elevation is simply a function of the flows into the lake and the maximum outflow allowed by the stream channel.”

Last summer as the lake reached historically low levels, local residents and business owners called on SKQ operators to limit outflow from the lake, which would have violated the federal operating license. On the other side, many state and federal officials, including U.S. Rep. Ryan Zinke, R-Mont., requested Hungry Horse Reservoir be partially drained to fill Flathead Lake. The interagency technical management team that coordinates the Columbia River Basin hydropower projects deemed the request unfeasible, as it would have required drawing the reservoir down too far, risking fall operations.

The jurisdictional overlap between tribal, state and federal dam operations, as well as the mixed-use management of the waterways created a lot of confusion last summer about what could be done over low lake levels during a drought. To provide more timely and transparent communication to the public, water managers have prepared a series of informational sessions throughout the spring, starting with Thursday’s, which has been archived.

“This is the first of many collective efforts on all our parts to keep you informed as we continue down this path of adjustment,” Lipscomb, the Energy Keepers CEO, said. “I think it’s important to appreciate that as we continue to progress to a warmer climate, the path to get there is not always going to be smooth and peaceful.”

“Our homelands here in western Montana continue to be a beautiful place, that’s something we should keep in mind. They were prior to these climatological impacts that we see today, and they will be long after the changes that are yet to come have materialized,” he continued. “The challenge to us as humans is how we adjust and remain resilient. That’s where I hope we start to focus our efforts.”

The full presentation and a list of frequently asked questions can be viewed online here.