Land Board Votes to Protect 33,000 Acres of Northwest Montana Timberland

With support from the wood products industry and conservation interests, the Montana Land Board's 3-1 vote ensures working forests between Kalispell and Libby remain in timber production while allowing public access in perpetuity

By Tristan Scott

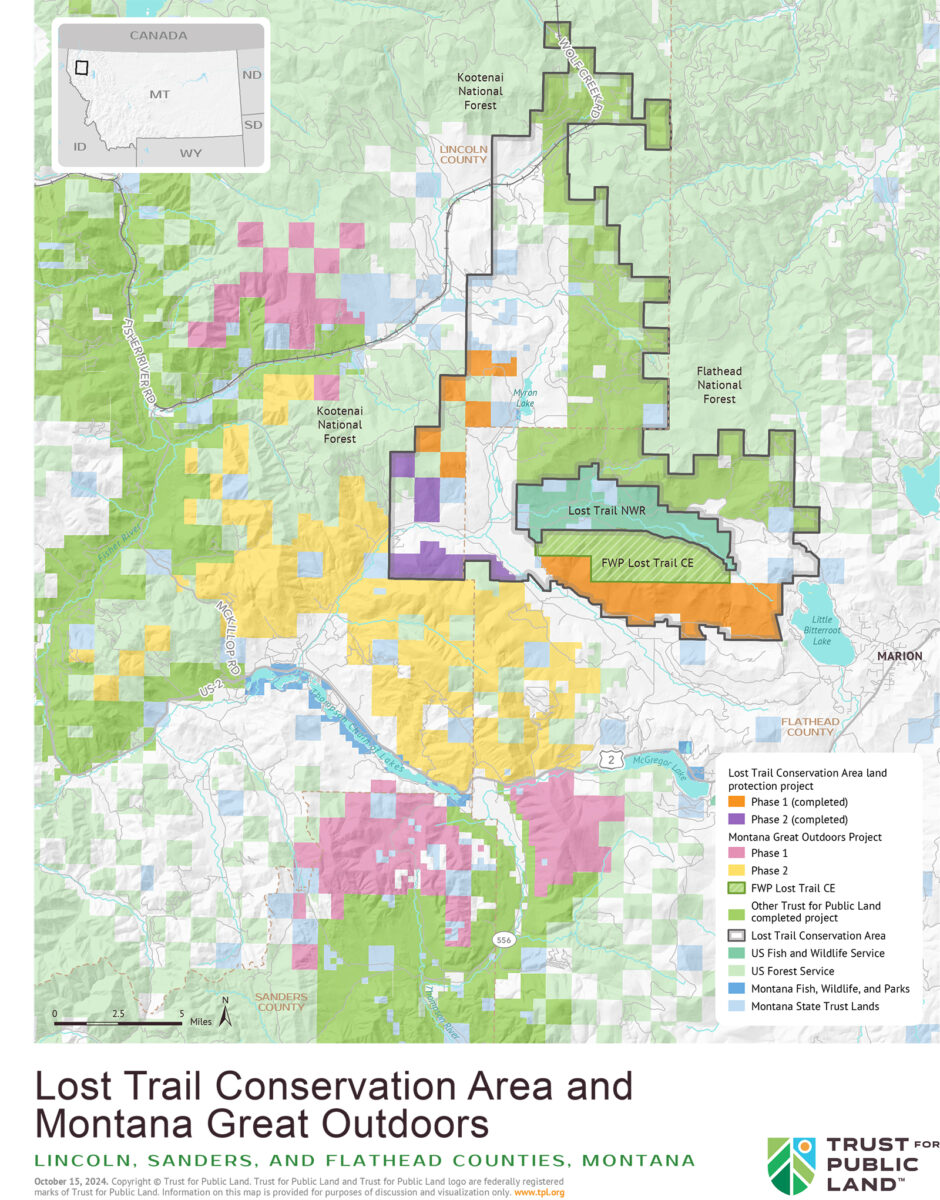

The Montana Land Board on Monday approved a deal to protect a swath of private timberland between Kalispell and Libby, placing nearly 33,000 acres of working forest under a conservation easement that preserves public access, precludes development and maintains the parcel for timber production. Widely viewed as serving the long-term regional interests of corporate timber while also providing a boon to wildlife conservation and public recreation, the easement received support from a broad coalition of stakeholders.

Called the Montana Great Outdoors Project, the easement with Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks (FWP) was designed to preserve key fish and wildlife habitat while guaranteeing the timber company’s right to manage the land for production. The 3-1 vote on Monday cleared the way for the first phase of a two-phase project totaling 85,792 acres of timberland owned by Green Diamond Resource Company.

According to Julia Altemus, executive director of the Montana Wood Products Association, the trade group supports the project because it assures the landowner will continue to manage the land for forest health, fire resilience and timber production. By her estimates, the easement can produce a sustained annual harvest of 20 million board feet of merchantable timber, supporting 40 full-time workers and 100 seasonal workers. The timber would be processed regionally, generating $30 million per year in economic activity.

“We are frequently asked what the state can do to support the forest products sector,” Altemus wrote in a letter of support for the project she submitted in September. “These questions have increased with the recently announced mill closures in Seeley Lake and Missoula. One of the answers to that question is to support proposals that keep Montana’s working lands working and generating long-term, sustainable and reliable fiber for an industry that has faced significant reductions in recent decades.”

Jason Callahan, Green Diamond’s policy and communications manager, said the Seattle-based company’s support for the project, as well as a suite of other conservation easements either proposed or completed on its checkerboard of Montana timberland, is rooted in its tradition as a family-owned forest management company.

“This conservation easement is attractive to us because we retain full ownership of the land and full management discretion. It’s called a conservation easement but that’s just the name we’re given. We consider it a working forest easement,” Callahan told the Beacon in October.

Acknowledging the intensifying development pressures bearing down on private landowners in northwest Montana, including routine, unsolicited purchase offers, Callahan said simply, “we are not a real estate company.”

“We are a forest management company. That is what we do. We have been managing forests since 1890 and we want to continue managing forests. Our company’s president wants to see his grandchildren be able to access these forests. This is a generational investment. This land needs to rest. It needs sustainable forest management over the next 15 to 30 years before it’s capable of paying for itself again. And because our development rights have conservation value, this project allows us to monetize them. The conservation easements give us the bridge funding until these forests are back to full production.”

By removing the block of land from private development interests, the deal also leaves intact a vital migration corridor and year-round habitat for moose, elk, mule deer, and white-tailed deer, preserving the public’s ability to hunt the land.

The state land board consists of Montana’s five top elected officials: Gov. Greg Gianforte, Secretary of State Christi Jacobsen, Attorney General Austin Knudsen, Superintendent of Public Instruction Elsie Arntzen, and Securities and Insurance Commissioner Troy Downing.

Although the five-member board gave initial approval to the conservation easement in October, its members revisited the issue at the Dec. 16 meeting to address Jacobsen’s concern that a provision of the easement explicitly protect third-party mineral rights. With that condition satisfied, the board approved the easement in a 3-1 vote; Arntzen voted against the easement while Knudsen was absent.

Proponents of the Montana Great Outdoors Act, the first phase of which protects 32,981 acres in the Salish and Cabinet mountains, described it as the culmination of a years-long effort by FWP, the nonprofit Trust for Public Land (TPL) and landowner Green Diamond Resource Company, which in 2021 purchased 291,000 acres of private timberland from Southern Pine Plantations (SPP), the real estate and investment company that in 2019 bought 630,000 acres from Weyerhaeuser Co., which acquired the land in 2016 from Plum Creek.

Despite the succession of private ownership, the land has been managed for de facto public access for more than a quarter century, in large part because the timber companies have been invested in long-term forest management as opposed to piecemeal development deals. But as demand for land intensifies in this corner of the state, so has a campaign to furnish permanent protections on northwest Montana’s working forests, which under a conservation easement can continue to produce lumber for local mills while allowing public access and preserving wildlife habitat, even as the state collects property taxes.

Barry Dexter, director of resources at Stimson Lumber Company, which owns hundreds of thousands of forested acres spanning northwest Montana, northern Idaho and northeastern Washington, said the pressure on landowners to sell has already converted the region’s timber base to non-forest uses; at one point, Dexter said he was receiving unsolicited offers on an almost daily basis.

“I’ve been personally associated with these forests for over five decades, so I have seen this large private timberland landscape dwindle down to what’s left now,” he told the land board at its meeting in October. “So we are truly at a critical point where we can try to preserve what’s left or we can just allow it to be developed.”

The effort to preserve what’s left has become a rally cry in recent years, particularly after SPP sold 475,000 acres through 49 land sales in the span of a year, with the sales ranging in size from 4 acres to the 291,000 acres Green Diamond acquired.

Even with the groundswell of support for the Montana Great Outdoors Conservation Easement project, it wasn’t an easy sell to some members of the Montana Land Board.

Of the roughly 150 comments submitted to the land board regarding the Montana Great Outdoors Conservation Easement project, including letters of support from trade associations such as the Montana Wood Products Association, and from sportsman groups including the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, one significant stakeholder opposed it — WRH Nevada Properties, LLC, of Rexburg, Idaho, which owns 42% of the property’s mineral rights underlying a large segment of the project area.

Peter Scott, who represents Citizens for Balanced Use and WRH Nevada Properties, on Monday said he still wasn’t satisfied with the easement’s amended language, which makes clear the mineral rights would not be diminished. Arntzen, who has previously expressed her opposition of easements that don’t include a lease term, seized on Scott’s concern when she floated a failed motion to delay the vote until next spring, after the two incoming land board members replace her and Downing.

“It’s not to delay but to have this discussion and the vote at a springtime date,” Arntzen said.

But Downing and Gianforte weren’t swayed, with the former insisting the land board had already addressed the issue and “that relitigating this sets a bad precedent for the land board.” Gianforte said if he were to entertain supporting Arntzen’s motion, the project would become “a perpetual agenda item.”

“Superintendent, I recognize you have opposed this project from the beginning and that delaying it is one way to kill something,” Gianforte said. “But this has the support of all the communities’ county commissioners, as well as local advocacy groups and the landowner. It was negotiated over a lengthy period of time and I feel a strong compunction to honor the local consensus that has been built around this, which I think has been recognized in this amended language.”