CFAC Watchdog Group Says EPA Weighed Cost-savings Over Superfund Cleanup Efficiency

Pointing to an 18-month community engagement process and a “responsiveness summary” spanning hundreds of pages, federal officials insist they selected the most protective option before finalizing a cleanup plan for the contaminated site near the Flathead River

By Tristan Scott

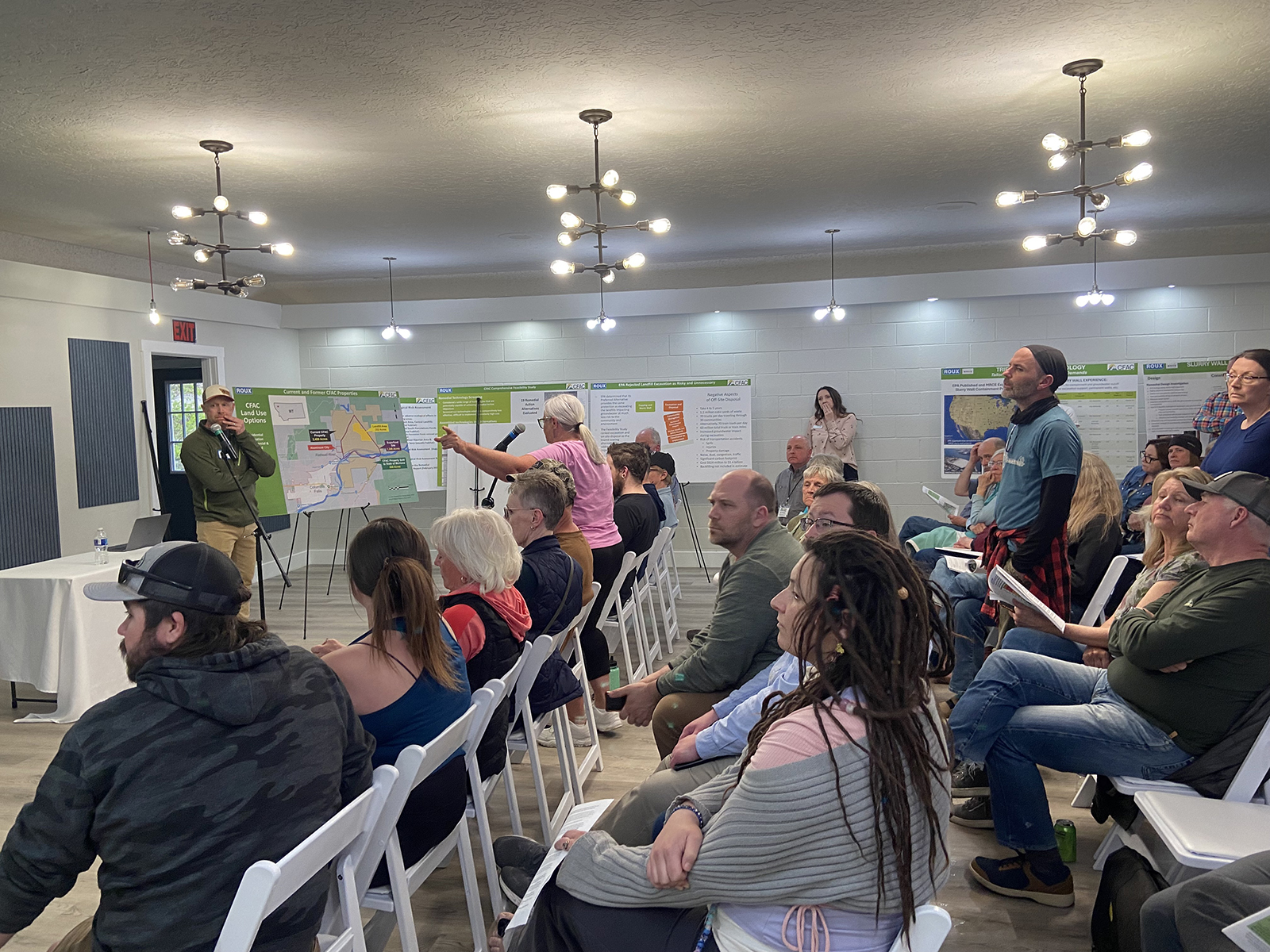

In a 432-page decision document finalizing a cleanup strategy for the Columbia Falls Aluminum Company (CFAC) Superfund site, remediation experts with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) spent about half of it responding to concerns raised by members of the public during an 18-month engagement process. Still, in a sign of the magnitude of community interest and the high stakes of a toxic cleanup project along the Flathead River near Glacier National Park, a local watchdog group has accused the federal agency of dismissing the public’s concerns while prioritizing corporate cost-savings over environmental safeguards.

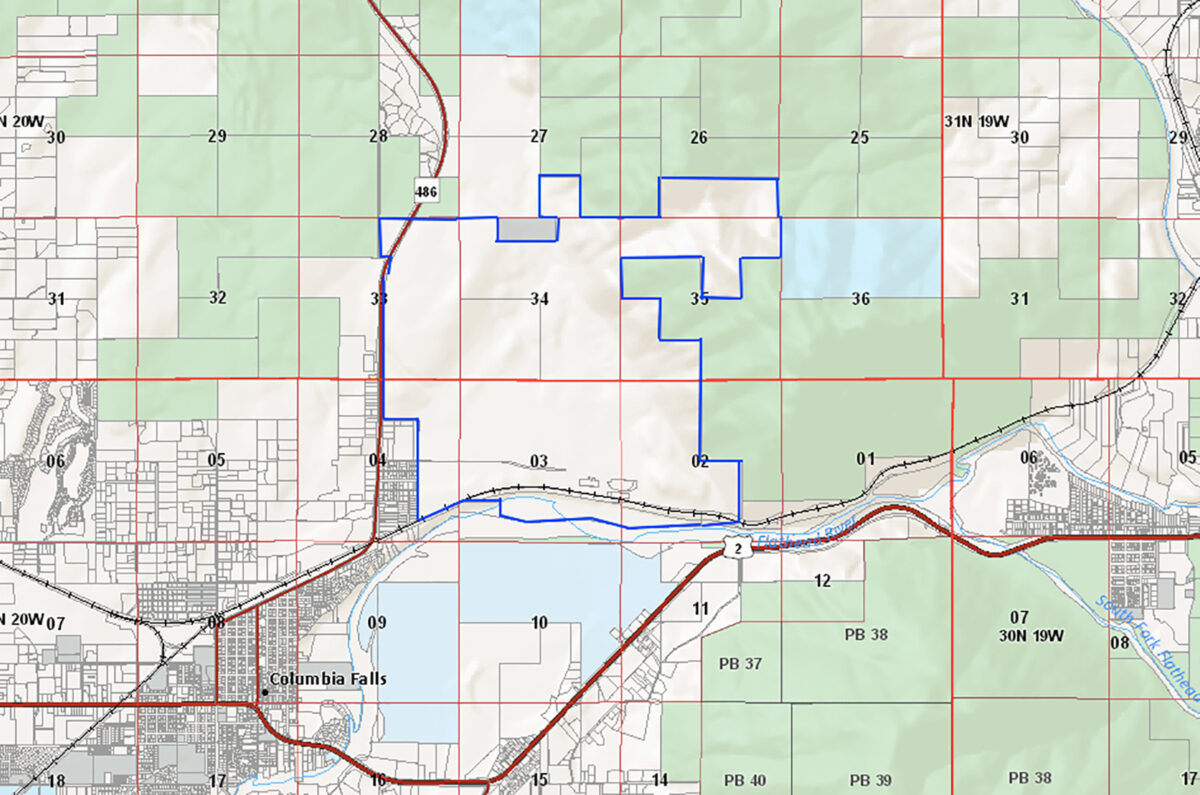

The EPA’s Jan. 10 announcement that it had chosen a “preferred cleanup alternative” — first presented for public comment in June 2023 — signaled a key milestone in an environmental remediation saga that began in 2016, when the federal agency announced it was adding the CFAC property to the Superfund program’s National Priorities List, designating it for critical cleanup among the nation’s most contaminated sites. The investigation proceeded with little fanfare until last year when Swiss commodities giant Glencore, which owns the CFAC site, announced plans to sell the property to a local developer, Mick Ruis. While the terms of the sale are confidential, the deal is contingent on EPA finalizing the details of the proposed cleanup plan by selecting its preferred cleanup alternative, listed in technical documents as Alternative #4 (out of six alternative options).

Community interest intensified soon after those details emerged publicly last year, while the grassroots Coalition for a Clean CFAC (CCC) formed a year earlier to hold the federal agency accountable, urging EPA to pause the final cleanup decision while investigating its own course of remedial action.

Last week, when the EPA published a record of decision (ROD) finalizing its cleanup strategy at the CFAC Superfund site without incorporating the group’s findings and input, CCC board members wrote a letter accusing the agency of paying “short shrift” to the public while aligning its cleanup strategy with the interests of the contaminated site’s corporate owners.

“While the EPA’s Record of Decision (ROD) recently issued for the Columbia Falls Aluminum Company Superfund site is dismaying, EPA leadership’s failure to do so without actionably taking into account public and community concerns and numerous technical issues raised but repeatedly dismissed, is quite appalling,” according to the letter from the coalition, which received funding assistance from EPA to conduct its own site analysis, which CCC called a “Deep Dive.”

“Despite over 800 formal written comments and petitions to EPA from organizations and individuals representing some 20,000 plus Montanans, most all of which favored removal and treatment of these hazardous wastes, EPA gave unexplained preference to the cheapest option of mere containment over treatment, which only serves to benefit Glencore, one of the world’s wealthiest corporations,” the letter states, describing CCC’s preference to excavate the toxic waste and treat it before entombing it on-site.

The cleanup plan’s central focus involves the former CFAC plant’s west landfill and its wet scrubber sludge pond, where experts have pinpointed the highest concentrations of contaminants. Most concerning, officials say, is that the groundwater plume underneath the unit is laced with poisonous amounts of cyanide, arsenic and fluoride, which are the byproducts of the aluminum smelting process that occurred for more than a half-century. EPA officials also raised concerns about excavating spent pot liners — a hazardous byproduct of the aluminum smelting process — due to “the potential explosiveness and release of toxic gases.”

“As previously discussed, the EPA has serious concerns about the implementability of treating excavated mixed wastes from the West Landfill and Wet Scrubber Sludge Pond,” EPA officials stated in the agency’s response to CCC. “The EPA also believes that the current groundwater contaminant plume poses a relatively low long-term threat for the human health and ecological risk reasons discussed above.”

According to EPA, cost is a central factor in all Superfund remedy selection decisions, but it is not the only factor in the criteria it must consider. The Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA, commonly referred to as Superfund) establishes five requirements for the selection of cleanup remedies: Protect human health and the environment; comply with applicable or relevant and appropriate requirements (ARARs) unless a waiver is justified; be cost-effective; use permanent solutions and alternative treatment technologies or resource recovery technologies to the maximum extent practicable; and satisfy a preference for treatment as a principal element or provide an explanation in the ROD why the preference was not met. In selecting its preferred alternative, and in ultimately rejecting CCC’s preference, EPA officials say they employed an objective numeric ranking system.

“In summary, cost is one of multiple balancing criteria and must be considered in a CERCLA analysis,” the EPA stated in its response to CCC. “As a result, for alternatives with similar scores, the EPA appropriately considered cost, but it was not the only nor the most important criterion considered.”

According to Matt Dorrington, EPA’s project manager for the CFAC Superfund site, the agency went above and beyond its duty to address community concerns and respond to public comments since releasing its proposed cleanup plan on June 1, 2023.

“I think it’s important to emphasize that EPA thoughtfully considered and responded to all comments and feedback over the 18 months following release of the proposed plan,” Dorrington said in an email. “First, in the responsiveness summary (Part III of the ROD) where we received close to 800 comments (roughly 10% were from CCC core members). Second, in the form of fact sheets that contained clarifications to the many themes that emerged from enhanced engagement [between February and September 2024]. Third, through one-on-one discussions in Columbia Falls over the summer that you witnessed firsthand. And finally, in communications like these, where EPA took the time to respond thoughtfully to work products developed by the CCC during their ‘deep dive’ activities.”

According to the section of the ROD that describes the ways in which EPA fulfilled its public responsiveness duties, roughly 31% of the commenters were residents from Columbia Falls or Aluminum City, the residential neighborhood that abuts the Superfund site. Approximately 40% of the comments were identical or differed only by a few words, according to EPA, which prepared a total of 61 responses addressing the comments received. Comments were received from CCC beginning in January 2024.

One key element in the EPA’s selected cleanup remedy involves building an underground containment barrier called a slurry wall to isolate waste and prevent the migration of contaminants, including cyanide and fluoride, into the groundwater. Some members of the public were concerned that the slurry wall had the highest potential to fail, and wondered about the logistics of removing the toxic waste and transporting it off-site for disposal — a strategy EPA studied closely.

“The EPA also evaluated the cost of off-site disposal, estimating it as ranging from $625 million to $1.4 billion, compared to the $57.5 million cost of the preferred alternative,” according to the ROD. “The agency also evaluated the logistics of off-site disposal, including excavating about 1.2 million cubic yards of hazardous waste from the landfills, which would need to be dewatered and carted off site to the nearest Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) landfill in Arlington, Ore., nearly 500 miles away.”

Based on its “deep dive,” for which the CCC received Technical Assistance Services for Communities (TASC) grant money from the EPA, the coalition arrived at a different conclusion, recommending a strategy that involves excavating and consolidating the waste for containment in a newly constructed on-site repository “meeting substantive RCRA … requirements for modern hazardous waste impoundments.”

“As opposed to our initial recommendation where the Coalition, as well as the City Council of Columbia Falls, supported off-site transportation of the highly toxic waste left behind at the CFAC site to an off-site commercial hazardous waste facility, we are now tentatively advocating for [an alternative] which calls for building an on-site certified and highly regulated hazardous waste facility within the 1,340-acre Superfund site.”

The coalition also presented its findings in a letter whose recipients included Montana Gov. Greg Gianforte, the state’s congressional delegation, members of the Columbia Falls City Council, and the Board of Flathead County Commissioners. In the October 2024 letter, CCC urged the elected leaders “to stand united in telling EPA that they must pause decision-making” and delay the issuance of the ROD.

“Having spent the past 3 months researching the more than 10,000 pages of the EPA records, which Glencore’s consultants primarily wrote and compiled and the EPA relies on to justify the selection of Alternative #4, we are obligated to share our opinion that Alternative #4 is a raw deal for the Flathead, is not as protective as other feasible alternatives, and relies more on hopes and prayers for a permanent solution to toxic clean-up than it does best available science,” according to the letter.

EPA officials provided a detailed response to CCC’s October letter, including information on the proven effectiveness of slurry walls; the role of cost in the Superfund remedy selection process; the benefits of Alternative #4 as both a containment and treatment remedy; and an assessment of CCC’s preferred alternative, which the agency described as being “extremely difficult, if not technically impracticable, to implement” and which “may also exacerbate the groundwater contaminant plume.”

While EPA concedes the CCC’s preferred alternative ranked highest for long-term protectiveness, “it had the lowest rating for implementability.”

“It would require an estimated 4-5 years to excavate the estimated 1.3 million cubic yards of aluminum refining wastes and underlying contaminated soil,” according to the EPA’s response to CCC. “Excavation would take even longer if solidification and stabilization measures were conducted prior to placement of wastes in a lined repository. The possibility of encountering unknown waste types would require an evaluation of solidification/stabilization alternatives for these unknown waste types which would further expand the construction timeline. The excavation site would be open for years. Despite best management practices used to limit stormwater and snowmelt runoff into the construction work area, the open excavation would allow some precipitation to infiltrate the exposed wastes. Infiltrated precipitation would leach additional contaminants into the groundwater, which, in addition to the existing seasonal contact of wastes with groundwater under high water table conditions, would likely increase contaminant concentrations in the upper aquifer.”

According to John Stroiazzo, Glencore’s project manager at the CFAC site, nothing in the ROD should affect the pending land deal with Ruis, who intends to develop the property for residential and commercial uses. The roughly 400-acre parcel with the highest concentrations of contaminated waste would be carved out of the land sale under the terms of the deal.

“The sale is predicated on the proposed plan,” Stroiazzo said last week. “If the proposed plan does not change materially than the sale goes ahead. If we’re happy and he’s happy and the ROD is based on the proposed plan, then I don’t foresee any issues there.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly implied that the Coalition for a Clean CFAC formed last year. The grassroots organization began organizing in June 2023 after EPA issued its proposed cleanup plan.